PETIPA AND POLITICS

In college I took one of those life-changing, niche courses that liberal arts schools like to put on their brochures, called Dancing the State: Dance and the Political. In it, we watched Ballet Folklórico de México and dissected how its aesthetics were used in the construction of the Mexican statehood project. We studied ways in which Maya Plisetskaya encoded resistance into her dance in Soviet Russia; in the ballet Carmen, an outstretched leg held at a 90-degree angle could contain a veiled criticism of the surveillance state. We studied dance diplomacy; the US state department took American dance companies on tour to countries with totalitarian governments, showing American ideals of individualism and human freedom through a group of dancers. We studied Hula, its export, its use in Hawaiian indigenous resistance movements. We took dance apart as a movement language: how could dance be political? How could dance express pride, restage patriotism, or resist power? How could an art form deemed so superfluous (so joyful, so neutral, so feminine-coded) become a tool of propaganda or of freedom fighting?

Act 1, United Ukrainian Ballet's Giselle ( ©Altin Kaftira)

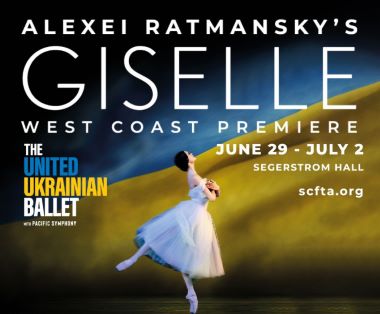

With my background in the political aspects of dance, I still could not quite predict the spectacle that was Thursday’s West Coast premiere of Giselle, danced by the United Ukrainian Ballet at Segerstrom Hall (there were gala appearances at D.C.’s Kennedy Center and the London Coliseum in 2022, the year this company was founded by Igone de Jongh, a former principal dancer with the Dutch National Ballet). The United Ukrainian Ballet is composed of dancers who were scattered to the four winds upon invasion and have been pieced together for a tour both here and abroad (their home is Den Hague, The Netherlands). Funded by Orange Count arts patron Elizabeth Segerstrom with proceeds going to BlueCheck Ukraine, actor Liev Schreiber’s non-profit organization, there was a champagne-colored carpet for celebrities (Sharon Stone, Mario Lopez, Kelsey Grammar, Sarah Jessica Parker). The 3000-seat theater? Packed.

The winning conductor Gavriel Heine and the Pacific Symphony performed Adolphe Adam’s gorgeous melodies live, and the music was truly magnificent. The two-act Giselle was then followed by an original modern piece with choreography by Emma Evelein. The piece, entitled Airlift, featured Oleksander Teren, a Ukrainian soldier whose legs were severed by a Russian shell in combat. And then, for the finale, the dancers sang the Ukrainian national anthem and waved Ukrainian flags, one of which was half Stars and Stripes. The audience leapt to its feet with palpable emotions electrifying the air.

Elizaveta Gogidze as Giselle and Oleksii Kniazkov as Albrecht Act 1, United Ukrainian Ballet's Giselle ( ©Altin Kaftira)

Giselle is the most popular surviving gem of the romantic period in ballet (1827-1870) which tells the tragic tale of a young peasant woman who is seduced by Count Albrecht (Alexis Tutunnique) masquerading as a commoner, and dies of a broken heart once it’s revealed that he is already betrothed. She comes back as a ghost – a “wili” (most certainly the origin of the phrase, “it gives me the willies”) – and dances with the other wilis and with Albrecht until dawn when she returns to her grave.

Alexis Tutunnique as Albrecht and Cristine Shevchenko as Giselle Act 1, United Ukrainian Ballet, ©Mark Senior

A product of romanticism in arts and literature, Giselle is preoccupied with the spiritual essence of the ethereal or divine feminine. The technical innovation of the ballet is that the wilis keep their arms low and relaxed, while they jump as high as possible, creating the illusion that they float. The arms are flowing and willowy, which disguises the athleticism of this ballet; it’s a marathon to dance with its many jumps and countless precarious balances. One has to be very strong and muscular on the bottom, and dainty and graceful on top.

Elizaveta Gogidze as Giselle and Oleksii Kniazkov as Albrecht Act 1, United Ukrainian Ballet ©Altin Kaftira

Despite the moving political message of this particular performance, as a dance critic I would be remiss if I didn’t honestly assess that the United Ukrainian Ballet does not do a good job of dancing Giselle, created specifically for the company by Ukrainian citizen Alexei Ratmansky, artist in residence at the American Ballet Theatre. The technical elements that make this ballet a timeless treasure are not present. In the first act, these dancers barely get off the ground, don’t take up space, and seem to have trouble getting and staying on pointe. The men are slightly more watchable than the women, but the technical level of the company is low, even compared to the national companies of other post-Soviet-bloc Eastern European countries.

The Wilis and Elizaveta Gogidze as Myrtha Act 2, Giselle, United Ukrainian Ballet Giselle ( ©Mark Senior)

The interesting part about Giselle from a contemporary perspective (at least to this author) is that the ballet starts with a predictably homely peasant atmosphere filled with pantomime in Act I, and then in Act II deposits us in a macabre world of robotic and murderous fairies, who at one point execute Giselle’s suitor Hilarion in a dance to the death. The queen of the Wilis, Myrtha, is one of the most memorable roles in Giselle; she is usually played as a fearsome dictator, and her role includes a lot of jumping, chugs in arabesque, and breakneck turns. In this version, Myrtha (Vladyslava Kovalenko) was interpreted daintily and softly. Giselle, whose central trait is the love of dance, despite her life-threatening heart condition, was performed similarly without power or control — albeit with some graceful acting — by Christine Schevchenko from American Ballet Theatre. Likewise the very tall Alexis Tutunnique, whose height may have contributed to his trouble finding his center of gravity. The divertissement dance “Peasant Pas de deux” was innocently witty as Maksym Bilokryntski and Daria Manoilo celebrated peasantry in oddly lightly colored costumes borrowed from the Birmingham Royal Ballet.

Wilis Act 2, Giselle, United Ukrainian Ballet ( ©Altin Kaftira)

It made me sad, as a balletomane, to hear the audience react with laughter when Giselle’s veil was shoddily pulled off in her entrance, or when she was placed inside her grave again. Moments that can be enormously powerful and serious when performed well were hokey and comedic in this production, but the audience was neither aware of the dancers’ technical shortcomings, nor seemingly at all concerned with the dance itself. They might have watched anything, had it also been sealed with a display of Ukrainian solidarity. It would have scratched the itch to feel empathy for Ukraine and anger at Russia, or to participate in a political pep rally.

Wilis Act 2, Giselle, United Ukrainian Ballet ( ©Altin Kaftira)

The irony of this production becomes clear when one considers that a Russian performance (whether by the Bolshoi or Mariinsky) of Giselle would have surely been powerful and flawless, as would many American productions; the resources that these two bipolar powers devote to the arts as robust cultural currencies dwarf Ukraine’s soft and sweet, but weak dancers. To use ballet as cultural diplomacy for Ukraine is ignorant (of Russian supremacy in the form) at best and politically irresponsible at worst. And the American audience’s enthusiasm for this low quality, insipid form of Giselle gave me phantom images of the criticisms often levied against Americans; that we worship power and money, that we have no concept of dignity or culture, no deeper meaning to our excess and consumption. The evening left a bitter taste in my mouth.

Wilis Act 2, Giselle, United Ukrainian Ballet ( ©Altin Kaftira)

One of the most vivid things I learned in my dance and politics class was that in the Soviet Union, when the government wanted particularly to hide a piece of news from its people, it would play re-runs of Swan Lake on Television. In other words, when the Berlin Wall fell, when the Cuban Missile crisis happened, Soviet citizens who turned on their TVs saw rows of pristine white swans gliding across the screen. The Russians gave us everything about ballet we still prize today: Tchaikovsky, Prokofiev, Ivanov; the Nutcracker, Sleeping Beauty, Swan Lake, Don Quixote, Plisetskaya, Osipova, Baryshnikov, Nureyev, Nijinsky, and Marius Petipa (whose brother, Lucien, created the role of Count Albrecht opposite Carlotta Grisi, for whom Giselle was created); In St. Petersburg, the Imperial Ballet sat across from the Military Training Academy, the juxtaposition of the twin arms of the Russian Empire: precision in art, in peacetime, and in violence, in wartime. The two are inextricable. What most people don’t understand about ballet is that it is a close bedfellow of European imperialism, and its beauty, for better or worse, derives from that militancy. Ballet – real ballet, not toddlers spinning in tiaras – is profound because of the duality of power and grace.

Wilis Act 2, Giselle, United Ukrainian Ballet ( ©Altin Kaftira)

The United Ukrainian Ballet displayed none of the power and strength that undergirds a ballet like Giselle, but I actually thought that the American audience not only tolerated that lack, but enjoyed the performance all the more because of it. The standing audience at the end, moved and titillated by Oleksander’s prominently displayed prosthetic legs in the encore, seemed to enjoy their own tears. It moved me, too, profoundly, but not only because of the tragedy of war, but because of the needless repetition of the sadism of the casually powerful. I tried to be conscious of the utility of this performance – perhaps it served the purpose of reinvigorating pro-Ukraine sentiment at a time when it is so desperately needed. But the evening struck me as not really being about Ukraine, in the same way that it was not about ballet or art. It was about us, about America, about a feeling of superiority derived from propping up a small and defenseless creature. On the same night as the premiere of Giselle, just a few miles away, BPOC (Ballet Project Orange County) was performing The White Feather, an Iranian ballet about a princess who fights evil forces, an allegory of the anti-femicide protests erupting across Iran. Did that have a packed house with champagne carpet and celebrity invite list? Surely not.

The Wilis and Elizaveta Gogidze as Myrtha Act 2, Giselle, United Ukrainian Ballet Giselle ( ©Mark Senior)

On the other hand, the other thread that particularly moved me was the moral of Giselle. Because of the inadequacy of the dancing, I was able to focus more intently on the pantomime (of which there is no shortage) in act one. I had never before noticed how prescient the story is; it’s the anti-Cinderella. Instead of a ballet about a low-class woman riding the principle of the democracy of beauty to become a princess (Cinderella), Giselle features that classic pastime of the wealthy, slumming it. The prince does a little class cosplay to go to a quaint village and seduce the peasant Giselle, and then their love becomes real, and then he is exposed as the powerful symbol of state force that he is, and she dies as a result. It’s a story of inequality, unfairness, and deceit. That the protagonist dies at the end of Act I, but Act II is the main event, is a testament to the belief in an afterlife, the romanticism of the concept that the earthly realm in which we live is not the only reality. In many ways, it shows the triumph of the meek, the righteous, over the vain and mighty.

Elizaveta Gogidze as Giselle and Oleksii Kniazkov as Albrecht Act 2, United Ukrainian Ballet ( ©Altin Kaftira)

Though lost on the audience, in this vein, Giselle was the right choice for the United Ukrainian Ballet, despite their lack of technical precision, control, and strength. What they had, in spades, was softness, delicacy, grace, innocence. And this, in a way, is the moral of Giselle: the value of the delicate in a world that rewards brute strength. The quiet mouse sandwiched between massive beasts, like Ukraine itself. Interpreted metaphorically, Ukraine is Giselle: a young girl seduced by powerful entities disguising themselves as benevolent and loving, but still prizing force over sweetness. She may well die at the end of Act I. But there will be an Act Two.

Elizaveta Gogidze as Giselle and Oleksii Kniazkov as Albrecht Act 2, United Ukrainian Ballet ( ©Altin Kaftira)

Giselle

United Ukrainian Ballet

Segerstrom Hall in Costa Mesa

ends on July 2, 2023

for tickets, visit SCFTA

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

I totally agree with the author’s assessment and critique. I was at the July 1 performance, and I was almost in pain watching very mediocre dancing. I can’t believe Ratmansky would present this ballet to look like a high school production. I saw this ballet numerous times with great ballet stars and virtually unknown performers. This was not a professional performance. But I felt good supporting my country and singing the Ukrainian national anthem at the end. That one was delivered flawlessly by the orchestra.

I too was there and although not as educated as the others about all the intricacies of Ballet, always love watching it, as no matter how weak the performance, they are always 100 times more talented than myself. I did at times feel that it was a little lackluster, but over all still revealed such effort and training to be able to do those moves over and over. To me the stage seemed so small and I felt the performers were in a circus ring trying to present a much larger act, as if in a crowded room. They did some amazing passes in which they all seemed as if they would crash into each other and I just couldn’t believe how they still went in such a tight area and managed to pull it off. I think that although the music is magical it is very dated and along with the sweet love affair made it hard for people that are used to such mayhem and murder and major technical fireworks through every moment of the new movies hard to ingest all the splendor they were witnessing. Very fragile, very quiet and in its way magnificent, done by such traumatized people. Everyone was there to support the Ukraine and in the end I don’t think there was a dry eye in the place. I loved their rendition and being there was one small way we could support them, I would have clapped till dawn if it made them realize we support them and pray they will be liberated from this horror as soon as possible. God Bless the Ukraine!!