FRIDA PEOPLE

We live in the age of Frida Kahlo iconography. Distilled to the mere visual suggestion of a unibrow, braided updo, and flower headpiece, her image graces wall murals, tote bags, socks, umbrellas, T-shirts, and all manner of decorative objects the world over. Known during her lifetime primarily as the wife of Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo (often referred to by the mononym, Frida) now represents a franchise of cultural symbolism as ubiquitous as the Eiffel Tower or Statue of Liberty. Kahlo is a symbol of feminist resistance, indigenous consciousness, disability, workers’ rights, artistic subjectivity, and trauma-informed fantasy. She has been canonized as the secular patron saint of individuality: a brave Joan-of-Arc who resisted conformity and painted her version of the world against staggering social and physical odds.

I saw Dutch National Ballet’s touring full-length production of Frida at the Music Center’s Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. Choreographed by Colombian-Belgian rising star Annabel Lopez Ochoa to an original score by Peter Salem (interspersed with pre-recorded ballads by Chavela Vargas), the ballet traces Kahlo’s life story through motifs from her paintings. Originally adapted from a shorter ballet, entitled Broken Wings, for English National Ballet, it runs 2 hours and 15 minutes with a 20-minute intermission.

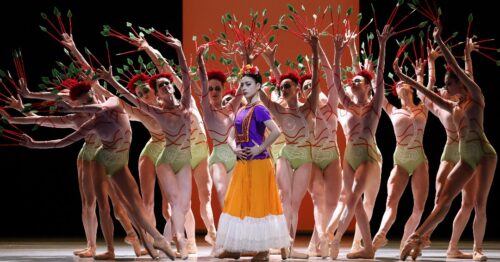

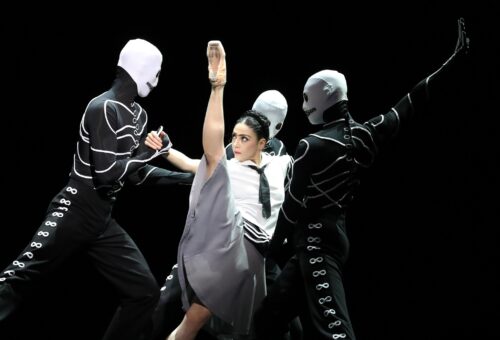

It begins with six skeletons, male dancers in skintight suits and spandex skull head-coverings, who dance around and atop a large black cube. Out of the cube pops the young Frida in school uniform. The skeletons and the cube (costumes and sets by Dieuweke van Reij) turn out to be recurring elements, the main visual mechanism of the ballet; the cube will at points become Frida’s sickbed, a raised platform atop which Diego paints, and the prop to stage her spirit’s ascension from the mortal world; the skeletons will be recast (keeping their skull head–coverings) as passersby in Mexico City, policemen in New York, and the divertissement in front of the curtain while sets are exchanged behind.

There are two main human characters to speak of in the ballet: Frida, played by Maia Makhateli, and Diego, played by James Stout. The others, with exceptions of minor characters, are animations of Frida’s inner world: the “deer,” the “bird,” and 10 larger-than-life versions of Frida herself, played by male soloists in colored spandex bodysuits. The style of movement, the program explains, is meant to evoke “Mexicanismo,” the two-dimensional magical realist style that both Kahlo and Rivera used in their painting. As interpreted by Lopez Ochoa, it’s grounded – a cross between ballet elements and modern techniques. The dancers eschew any complicated pointework in favor of creating shapes with their bodies. The “10 Male Fridas” do movements that could have been lifted right out of a Mark Morris piece, spinning in their long dresses and pumping their arms in angular patterns. When the few humans enter the ballet, whether Diego’s lovers or Frida’s, ballet vocabulary returns in the form of the inventive partnering for which Lopez Ochoa is best known.

Going into the evening, I had two main questions. How would ballet, a European imperialist art form, be used to portray the life of Kahlo, who espoused indigenous Mexican consciousness? And how would the ballet go about abstracting the elements of her life story that have now become museum store kitsch? The first question was answered by Lopez Ochoa’s “Mexicanismo” choreography, albeit inelegantly. The style of the ballet, especially as worn by the tall and lanky dancers of the Dutch National Ballet, appeared more caricature than evocation of Latin American movement. The intent was clear – ballet would have been too old-fashioned and aristocratic, so this clunky modern hybrid was necessary. But the style felt like a reduction of Mexicanism in dance. If anyone in the audience has seen Amalia Hernandez’s visionary choreography for the Ballet Folklórico de México, or even spent more than a half-day in the country, Lopez Ochoa’s “Mexican” movement style might appear little more than a paltry imitation.

To the second question, its handling of symbolism, I watched the ballet with an excellent, deep portrayal of Kahlo’s biography in the back of my mind: the Hollywood biopic Frida (2002). I find it to be a total artwork: Salma Hayek’s portrayal, Kahlo’s paintings shown side by side against the real life events that inspired them, director Julie Taymor’s precise eye, and the Elliot Goldenthal score woven seamlessly into and among Chavela Vargas’s aching ballads. It’s a meticulous recreation of the real person behind the symbols, the individual behind an avatar of individuality. The program hints that Lopez Ochoa was inspired by the film (“From the moment she saw a film about Kahlo’s life 15 years ago’¦”). That the film she saw was Taymor’s 2002 blockbuster is confirmed beyond doubt by the ballet’s musical choices: Vargas’s ballads are excised for use alongside the ballet’s score, sometimes exactly in the order they appeared in the film.

But unlike in the biopic, the visual symbols of Frida in Lopez Ochoa’s ballet are rendered reductive and inert. It’s as if ChatGPT had been asked to choreograph using only the film for reference. It’s not that the ballet is unengaging; it’s that if one has seen the film, the ballet is simply a lower quality rehashing of those elements. The visual styling of Young Frida is lifted directly from the film (she appears in schoolgirl’s skirt and starched button-down, fists clenched). Diego’s painting is rendered in movement as blustery arm motions at empty picture frames. The Mexico City street is represented by skeletons carrying wire-frame depictions of cars and buses. Diego Rivera’s 1934 commission for Rockefeller Center, Man, Controller of the Universe, is “destroyed” when skeletons dressed as policemen blow whistles and gallop onto the scene (meant to represent the real-life story in which Nelson Rockefeller had the mural scrapped because Rivera refused to paint over a likeness of Lenin.)

Even the ballet’s original elements (that don’t have analogs in the film) appear more as novelties than genuine creative engagement with the subject matter. The first time we see the Black Box (the main set piece), the 10 vibrantly colored male Fridas, or the deer or bird, we are engaged and excited. But after those introductions, those elements stay onstage with little variation or repetition. They become moving muzak and fade together. Does the “deer” have a purpose beyond loping demurely around Frida? Is the “bird” such an integral part of Frida’s imagery that she deserves to flit around the stage at all parts of her life story? The skeletons, undoubtedly meant to cleverly play many roles in Frida’s life with few dancers, came off rather as corny and hokey. A recurring motif features them slapping each other’s buttocks (without apparent reason for doing so.)

It’s this cartoonish quality – trying to capture the superficial aspects of, as opposed to abstractly engaging with Frida Kahlo’s life or art – that marks Frida as ultimately amateurish and uninspired. At the beginning of the second act, two little children with skull heads, one in a Tehuana dress (meant to evoke Frida) and one in a suit (Diego), do a little dance together in front of the curtain with the skeletons in tow. The audience lets out an audible “aww.” Even Makhateli’s dancing, technically proficient, lacks the depth, physical tension, and performance quality to scratch the surface of Kahlo’s real-life persona. However, as with so many dance performances in LA, the audience didn’t seem to be able to tell the difference between empty showmanship and nuanced artistry. They screamed and whistled at the end and I suspected much of this reaction came about because the ballet delivered on the promise of its premise; it was as satisfying as the purchase of a Frida Kahlo tote bag. As a marketing event, the performance was a success; many audience members came dressed as Frida, the one outing of the year when this kind of happy appropriative kitsch is not only allowed, but sanctioned. It was perfectly consumable, the kind of ballet that makes a great date night or gift.

The other main fault running through the heart of Lopez Ochoa’s version is that in the absence of meaty biographical details about her art (which are, of course, a challenge to portray in the abstract form of dance) the ballet’s narrative focuses almost exclusively on Kahlo’s disability and physical suffering. Much of Frida’s actual choreography was a kind of stylized writhing in pain. At one point, red columns of elasticized rope fall from the ceiling, calling to mind blood vessels, representing Frida’s miscarriages). While Frida’s physical shortcomings and suffering are an important aspect of her biography, without her paintings and intellectual activity, the ballet could be about any disabled woman. Its focus on Frida’s trauma veers into the gratuitous and glorifying.

All in all, I would skip this performance and rewatch the 2002 movie. While the partnering, Lopez Ochoa’s specialty, is truly innovative and stunning, one could get that in a shorter or abstracted piece of hers, like Broken Wings. Ultimately, Frida showcases more about the travesty of the intersection of capitalism and biography than it pays tribute to an extraordinary 20th-century artist.

photos by Hans Gerritsen courtesy of The Music Center

Frida

Dutch National Ballet

Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, 135 North Grand Ave

played June 14-16, 2023

for more productions, visit Dance at The Music Center

for more info, visit Dutch National Opera and Ballet