GRINDHOUSE 101

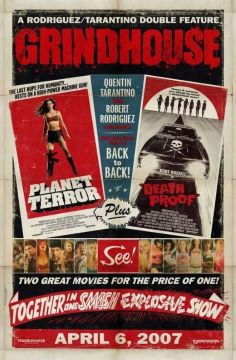

[Editor’s Note: An ode to Grindhouse films, the 2007 pic Grindhouse consists of two features, Planet Terror by Richard Rodriquez and Death Proof by Quentin Tarentino. Preceding and separating the features are faux trailers by Rodriguez, Rob Zombie, Eli Roth and Shaun of the Dead’s Edgar Wright. Grindhouse was a box office disaster, making only $25.4 million on a $53–67 (some say $80) million budget at the domestic box office. Due to underperforming, Planet Terror and Death Proof were released separately in other countries.

Tarentino has since purchased the Beverly Cinema in Los Angeles, and regularly screens original Grindhouse movies in 35mm. But what is Grindhouse you neophyte-filmgoers might ask? Our writer John Topping’s review and commentary from 2007 actually explains it brilliantly, so enjoy this article from our archives. You’ll be off to a Grindhouse screening faster than you can say, “Faster, Pussycat, Kill! Kill!“]

THE RETURN OF 70s NOSTALGIA

After walking out of the auditorium, one of my friends with whom I saw Grindhouse asked me if I liked it. It was with hesitancy that I had to admit, “Yeah, I did.” “It sounds like you’re ashamed to admit it.” Well, perhaps, but, if so, it wasn’t the deep, unforgivable kind of shame I felt when I had to admit that I liked Jackass Number Two. That was the shame of being an American who could sink so low as to not only be entertained by stupidity but be forced, however reluctantly, to defend the merits of its contribution to cinema. This time it was more of a disoriented disappointment that I actually did like it ’¦ a lot ’¦ and now would have to go home to a partner who, upon learning that circumstances dictated that I would be seeing Grindhouse before seeing the long-overdue American release of Killer of Sheep at the IFC, reacted something like a fundamentalist Christian learning that his spouse was about to see a porn film instead of The Passion of the Christ.

Grindhouse is a collaboration of five directors who experientially guide you through a simulation of a 1970s low-budget exploitation double-feature. For the benefit of those who were unborn or unobsessed with movies during this era, some background about this genre is appropriate: in the 70s, before the video revolution, movies did not depend on huge opening weekends for survival only to disappear in a matter of weeks (even if successful); when any film was released, one ordinarily had several months to see it on the big screen. After debuting in top-dollar first-run houses (about $3.00 where I grew up), it would later be released in second-run houses and drive-ins. (There were even Mom-and-Pop-operated third-run houses.) When a film started to lose traction as an entity unto itself, it would often find life in yet another run, released as a double-bill with another film of similar appeal. As a film traveled from first-run to second-run to third-run or further, the same prints were passed from movie theatre to movie theatre, accumulating untold amounts of dust and scratches. The dust caused abstract bee-swarm-like dots to appear on the screen (as if overlayed with a Stan Brackage film), while the scratches caused those vertical lines that dance around the screen, sometimes in pairs, sometimes in colors, sometimes in such multitudes that you could barely see the image. Also common were breaks in the film: after too many times through the projector, the film would snap, the reels would spin, and the projectionist spliced it back together, which would create a jump-cut in the picture and, because the sound and image are several frames apart on the actual strip of film, the interruption in image was separated from the interruption in sound; then to top it all off, the splicing tape would inadvertently become part of the sound track, translating aurally into a loud POP. Some film stock was so weak that you could not run it through the projector without it breaking at least once, effectively making, say, 5-minute scenes whiz by in a jolty 30 seconds. Combined with the inevitable scratches, it became a kind of avant-garde presentation. (When I was very young, those scratches were such an ingrained part of the film experience that I thought they were intentional.) It is these good old bad days of filmgoing that the five directors have sought – quite successfully – to recreate.

Rosario Dawson, Mary Elizabeth Winstead, Zoë Bell, Tracie Thoms

It’s a commitment to sit through Grindhouse, clocking in at 3 hours and 11 minutes, which encompasses two full length features and a handful of fake previews created especially for the film, as well as actual found footage of “Prevues [sic] of Coming Attractions” and other standard film stock of the era. 3 hours and change is nothing to serious cineastes who eagerly sit through multi-houred features on a regular basis. But it’s not just the technical compromises of the day that they are recreating. The style of films they are emulating – sometimes parodying but ultimately paying a perhaps overly fond homage to – are the B movies of the 70s; specifically, the cheapest, most quickly made exploitations of gratuitous sex and violence; the kind that usually debuted at drive-ins and second-run houses. This was not long after the breakdown of the traditional Hollywood studio system, but way before the studios became the kind of all-your-eggs-in-one-blockbuster corporations to which we’re all too accustomed now. With three whole television networks to choose from in all one’s waking hours, America’s insatiable appetite for entertainment was already entrenched. Not only were many more mainstream films made and released (and not only for teenage boys), these exploitation flicks filled in the gaps that studio Hollywood couldn’t. Led by the cinematic revolution that Easy Rider wrought, fueled with the newfound permissiveness that followed the 60s, and given free reign to test the boundaries of the new MPAA rating system (R and X both started as equally acceptable options), it gave rise to filmmaking in locations outside Los Angeles. Even if the financing originated in Hollywood, inexperienced casts and crews ventured out of town and out of state, creating a kind of hands-on self-taught film school, their only mission to return a product, on time and on a very low budget, with enough “money shot” footage to market an enticing preview and gain an audience.

These were movies made for and/or marketed to lower income demographics before words like “demographics” had entered the public lexicon. Double bills at second-run houses gave you triple the bang for your buck. Drive-ins were a haven for Mom and Dad to take the kids without concern that the screaming and crying would disturb the other patrons, who could drive to another spot if driven to it. One could indulge in consumables that were forbidden at indoor theatres: you could bring your own picnic basket of food and your favorite of alcohol while you freely chain-smoked cigarettes and passed joints. It wasn’t movie-going; parking was the event, and the films were secondary, almost inconsequential. Surely, along with television, drive-ins made their smaller but significant contribution to the reprehensible practice of talking throughout a film.

Rose McGowan, Naveen Andrews, Marley Shelton, Freddy RodrÃguez

Now in Grindhouse, great pains have been taken in striving to lower the technical standards of these otherwise accomplished filmmakers (Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez helm the two features; Eli Roth, Rob Zombie and Edgar Wright (+ Rodriguez) provide the previews). They have put as much of their first-rate skills into recreating second-rate filmmaking as the 70s filmmakers whom they are emulating had put into their own attempts to transcend their second-rate skills. It makes you wonder how carefully considered each intentional film break was. To what lengths did they go to recreate the quintessential 70s experience of sitting in a movie house when the film gets stuck, the image freezes, and magnified thousands of times before your eyes you see that frame of film burn to a crisp from the heat of the projector lamp? Did they insist on finding a way to see it burn in real time, to maintain the integrity of the era, or did they “cheat” with computer-generated animation?

Danny Trejo

The extent of your interest in the answer to these questions should be a barometer to how interested you actually are in seeing Grindhouse in the first place. For me, I went in expecting a nostalgia trip – and quite happily got it. But would I ever want to see it a second time? Well ’¦ while watching it I thought not, but since then I’ve been almost chomping at the bit to go again. Still, I can’t help but wonder: who else would this appeal to? Growing up in that era, I spent every available moment going to the movies: first-run Hollywood films, second-run double features (I actually saw Vanishing Point and Dirty Mary, Crazy Larry as a double bill, two films referenced repeatedly in Quentin Tarontino’s portion), drive-ins, revival houses, art houses, repertory cinema houses – even porno theatres when I reached legal age – anywhere a moving image was projected on a screen. I wanted to see everything, and that inevitably included these gratuitous exploitation films along with all the rest.

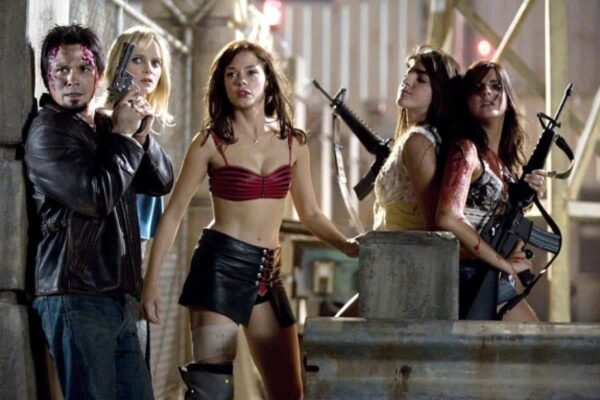

There is actually much more violence than sex in Grindhouse, as befits mainstream America’s eternally prudent tastes. The sex is mostly women with big tits, displayed for reasons that have nothing to do with character motivation, of course. The one actual sex scene happens in Rodriguez’s portion, the feature “Planet Terror”: two ex-lovers are thrown back into passion amidst a chaotic mini-armageddon-esque invasion by zombie mutants. They have an unlikely quiet moment together and use the time to reconnect sexually. Cue cheesy “sexy” music, followed by a montage of softcore imagery; but we never get to see their climax because the film breaks hurl us into the next scene.

Rose McGowan

The violence, however, is considerable, especially in this same Rodriguez portion. But it’s never violence that makes you – or, at least, never made me – really squirm. It’s simulated low-budget violence; that is, no matter how many buckets of blood spurt in every direction, no matter how many bodies are blown up or hacked in half or heads decapitated or limbs maimed or bones broken or eyes gouged – it’s purposely never convincing enough to make you believe anything other than the fact that you’re watching a movie; you might cringe at the idea, but never at the effectiveness of the execution (with the exception of some bubbling blood boils that earn some genuine “yuck!”s). Other delightful low-budget simulations are “exciting” pull-focus shots and other faux-attempts at bravura camerawork, “exciting” wall-to-wall cheesy music created by the director himself (which becomes quite tiresome but this is not about appeasing traditional tastes), and most delicious of all, what might only be called an entire school of low-budget acting (often unknown whether it’s rendered perfectly by the actor or cast perfectly by the director).

Michael Bacall, Jordan Ladd, and Sydney Tamiia Poitier

My favorite section of Grindhouse was Edgar Wright’s pseudo-preview of the faux-feature “Don’t.” By being the shortest original piece of the undertaking, it has the advantage of remaining truest to what it is emulating. Whereas the two features abound with anachronisms (everything indicates that the time is the 70s, but everyone has cell phones and blackberries) and there is a tendency, even in the other previews, to have at least one moment so over-the-top that we’re being winked at instead of taken on a ride of pure integrity, “Don’t” is pitch perfect as both comedy and homage. It’s a prototypical set-up of mod twenty-somethings lost in the country who must seek help in a strange dark mansion for dubious reasons, only to encounter endlessly unspeakable horror. In less than two minutes, we have the predictable story, the hairstyles, the clothes, the lighting, the camera angles, the editing, an ominous announcer (“if you’re thinking of opening this door ’¦ don’t!”), a complete absence of dialogue except for screams (so the American audiences don’t know it’s a British import until after they’ve bought their tickets), and the requisite scratches and film breaks to complete the experience. Arguably this is all we need to “get” Grindhouse in its entirety.

Kurt Russell

But Tarantino and Rodriguez don’t want you to merely taste the era, they demand to painfully grind you through the complete experience. That includes plot holes so big you don’t know if you’re watching the same movie anymore, entire reels of film missing (and thank God), and runaway storytelling that veers into the inconsistent, random, and downright numbing. If this were screening at a museum, you would probably walk in, watch for ten minutes, and then go back out to the paintings and sculpture, leaving those die-hard purists to watch it from start to finish.

Elise Avellan, Electra Stone

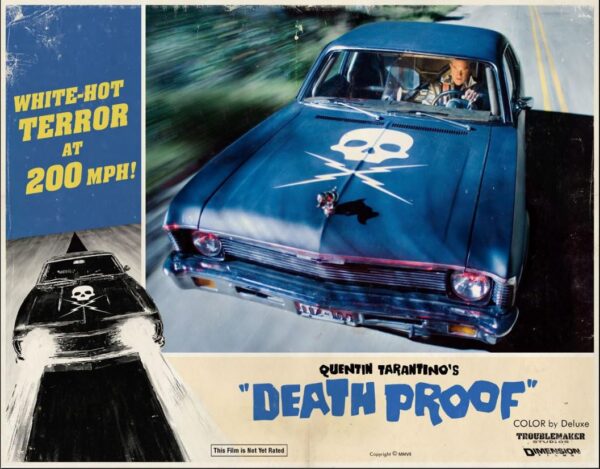

Tarantino’s feature within the feature concludes with a long and truly thrilling car sequence. But the vast majority of his “story” that precedes the thrills is mostly comprised of two different sets of women endlessly talking. Long, long sequences of stupid chit-chat: occasionally amusing, but mostly poorly written, cheaply shot, and badly acted – uninteresting on every level except that it’s supposed to be uninteresting, in homage to the low-budget films that actually used such long scenes of uninspired dialogue to pad the time between action sequences. The audience would have revolted except that it’s Tarantino; we trust there will be something worth suffering through this for, and we are thoroughly accustomed to the context by this time. But he really tests the limits of our patience, and one can imagine him giggling at our being forced to endure it. What fun he must have had whipping out bad dialogue that needed little if any revision!

Bruce Willis

Or did he? After the fact, I read this excerpt from an interview in Creative Screenwriting magazine: “I loved the dialogue that was coming out. I loved these girls and the way they talked; it was really genuine. This is the way girls talk now.”

Oh ’¦ he really thought it was good, well-written, believable dialogue. Whoa. (Um ’¦ it’s not.)

But that’s okay. Artists often give us something better than what they thought they were creating, or that gets appreciated differently than they had imagined. The ultimate question is, is it a worthwhile film? It’s meticulously made, it is absolutely unique, it evokes a bygone era brilliantly. But are the exploiting the market the same way but with a different slant? That is, making a big budget movie with esoteric appeal, but knowing fully well that the marketing and name recognition will ensure a profit from a largely unsuspecting audience?

That’s your axe to grind.

photos by John Sandau, Rico Torres and Andrew Cooper

Grindhouse

Troublemaker Studios

distributed by The Weinstein Company

released on April 6, 2007 | United States | RT 191 minutes | English