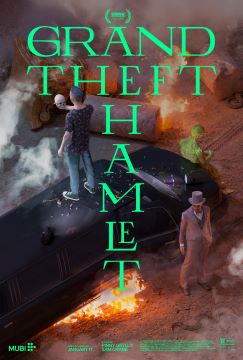

VIRTUAL VIRTUOSITY: HAMLET FOR THE GAMERS

Jokes thrive on bringing together the incongruous, and perhaps that’s why Grand Theft Hamlet is, at its best, fucking hilarious. The premise is simple yet audacious: what if the bizarre, glitchy bodies and hyper-violent, sensory-releasing spectacle of a video game like Grand Theft Auto (GTA) were used to stage Hamlet—a Twitch stream infused with the lofty aspirations of the Royal Shakespeare Company? At first glance, pairing Hamlet with GTA might seem like an exercise in bad taste. But instead, it’s startlingly effective–to say nothing of the insane challenges the actors-as-avatars encounter trying to mount this production inside the world of the game. It raises fascinating questions: why does it work so well? And what do we make of the absurd challenges faced by actors-as-avatars trying to mount this production within the game’s visual aesthetic, chaotic world? Somehow, the themes of Hamlet—its problems, its tensions—are not just preserved but clarified afresh and amplified. The garish violence of Los Santos–the game’s visual city–throws the slimy dynamics of Elsinore into sharp relief, drawing surprising parallels with our own modern urban gothic decay, where “Virtue itself of vice must pardon beg.”

Surely some of this is due to the sense of humor of filmmakers Sam Crane, a video artist and actor whose digital avatar is “Rustic Mascara,” and Pinny Gryllis, a doc filmmaker. As strange as it feels to admit, I’m thankful for the pandemic, which created the warped unprecedented circumstances that allowed this pair to conceive and execute such a wild scheme. As someone remarks late in the documentary, it’s like having an unlimited budget to do Shakespeare—specifically, “Like Elon Musk doing Shakespeare in LA.” Over the course of ninety minutes, we’re given a virtual taste of that hellishly hysterical vision, and it’s as outrageous as it sounds.

Some initial text sets us up: “This film is shot entirely inside the video game Grand Theft Auto Online. A violent and beautiful virtual world where almost anything is possible.” Filmed amid the UK’s third lockdown in 2022, the treat of playing GTA–or any number of video games offering the freedom to do whatever you want–becomes addictively tasty. At the time, theaters remained shuttered, leaving actors Sam Crane and Mark Oosterveen facing an uncertain and seemingly bleak future.

For almost the entire film, we remain immersed in the graphics of the video game, stepping outside only at the very end, when the filmmakers are shown accepting the Innovation Award at a Drury Lane ceremony. It’s worth noting that GT Hamlet isn’t exactly an adaptation of Hamlet—it’s an in-game filmed account of the attempt to stage the play within GTA. Yet these attempts, along with the rehearsals and eventual “performance,” inherently make it an adaptation—and an immensely valuable one. The fresh interpretations of Hamlet it offers (at least for me) are a testament to this. The voiceovers, which carry all the dialogue, create a strangely familiar yet effective form of animation, adding another layer of brilliance to the experience.

The film begins with Sam and Mark at a casino in Los Santos, playing a slot machine called Impotent Rage. True to form, GTA is hilariously on the nose in its depiction of mindless apocalypse (is that Idiocracy creator Mike Judge calling?). And yet, the concept of impotent rage feels oddly fitting—after all, Hamlet himself seems to grapple with it at various moments.

“What is a man

If his chief good and market of his time

Be but to sleep and feed? a beast, no more.”

And certainly those who play shitloads of video games sometimes are subjected (or subject themselves) to such captious pronouncements as Hamlet’s own:

“Sure he that made us with such large discourse,

Looking before and after, gave us not

That capability and godlike reason

To fust in us unused.”

During global lockdowns, we all had grounds for fusting. Hamlet, in particular, would have thrived in lockdown. Finally he’d have something to point to as an answer to his paradigmatic question:

“How stand I, then,

That have a father killed, a mother stained,

Excitements of my reason and my blood,

And let all sleep?”

When Sam leaves the casino, disgruntled by his bad luck at the machines, he uppercuts the valet and then guns down a businessman. I literally squealed with laughter. I’d forgotten just how violent these games are. “A bit of mindless violence,” Sam quips. Mark nods in agreement: “Anything to take you away from the crushing inevitability of your pointless life.” Hamlet, with his kaleidoscopic variety of self, shares this penchant for both blood and boredom. Exemplifying both, after killing Polonius he casually tells the Queen, “I’ll lug the guts into the neighbor room.”

Los Santos is Los Angeles, and like a fantasy city where the everyday person can do whatever he wants, Sam’s avatar stands out with blue hair, a mean fade, shades, and red streaks on his face. Meanwhile, Mark’s character is more normie in reg-colored coat and pants. Early on, they come across an outdoor arena, the “Vinewood Bowl,” the perfect location for their Hamlet. What else are they going to do? In real life, the boundaries between virtual and reality have blurred, making the latter feel less tangible.

Faces and bodies in many video games have weird repetitive tics, creepy distortions and mechanical gestures—hallmarks of what Freud might call the “uncanny.” The filmmakers manipulate all this, drawing unexpected emotion from the strange motions of digital bodies. For the first crack at the Bard, Mark recites the famous soliloquy from Macbeth. His character stands on the arena stage, pacing at times, making use of what arsenal of gestures the game provides. It’s absurdly funny.

Soon, Sam’s partner, Pinny—one of the filmmakers—joins the project. Serving almost as a stand-in for me, she doesn’t play video games herself. The first “scenes” between her character and Sam’s are woven with intimate conversations. They’re in a cozy virtual apartment, and it’s surprisingly sweet. Meanwhile, Mark reveals that he recently lost his father’s aunt—his last remaining relative. Now, as lockdowns persist, he braces for further loneliness as a partnerless, childless middle-aged man.

These moments of self-disclosure, though occasionally a bit tedious, offer a certain authenticity. They’re far more engaging than the repeated attempts to rephrase Hamlet’s famous speeches—efforts that feel neither insightful nor necessary. A prime example of this comes towards the film’s end, when they riff on Hamlet’s riff on humans as the “quintessence of dust.” At one point, someone absurdly declares that suicide is more a male problem. I can’t help but point out the ridiculousness of this, especially in light of a play where Ophelia arguably takes her own life.

Other players begin showing up in the game—prospective audience members—but they end up killing each other. This becomes a recurring issue when trying to stage a production of Hamlet (or do anything) in GTA. At one point, Mark, with classic British understatement, says, “If I could ask that you refrain from killing each other.” And then, while being shot at, “And don’t kill the actors either.” A full-blown mass shootout erupts, yet somehow, amidst the militarized mayhem, the play begins—the first run-through, as it were: “Who’s there?” “Nay, answer me. Stand and unfold yourself.” The answer to, “Have you had quiet guard?”–“Not a mouse stirring”–is madly ironic, perfectly in keeping with the text, where the guards are surrounded on all sides by rumors of a spectral presence, armament buildup, and looming menaces.

And thus begins the first attempt at GTA Hamlet. Sam and Mark quickly realize they need more players—people who can bring structure to the chaos. They understand now that this word—”recruit”—is deeply loaded in this merged world of video games and theater, where the lines between “real life” and surrogate bodies blur. Culturally and psychologically, it’s a concept this documentary is constantly exploring.

Though their attempt to make a video calling for auditions is interrupted by authorities who slide down ropes from choppers and kill them, Sam and Mark (whose characters are killed dozens of times) meet other player/characters—some reciting Shakespearean lines. An Arabic player, “parteb,” whose avatar is a humanoid alien with a nice ass, recites excerpts from the Qur’an. Chilling on her nephew’s gamer account, some aunt—a self-proclaimed “literary agent, mum, and fan of Hamlet”—seizes her only chance to perform Shakespeare’s masterpiece.

Then there’s Jen Cohn, whose claim to game-fame stems from her role as Pharah in Overwatch (I had to look up that free-to-play, team-based action game). We also have “djphil89” (these gamer handles, LOL), whose avatar swaggers into the arena audience shirtless in army shorts, sunglasses, and a top hat, only to punch the shit out of “fken776,” who naturally punches back and even starts shooting. “Dipo,” cast as Hamlet, shines in the role but eventually has to step away after landing a real-life job—he’s apparently a friend of Mark’s in that same digital world.

There’s a limit on the ability to actually sustain a performance of Hamlet in the game world of GTA. Celine Song, of Past Lives fame, staged a production of The Seagull using The Sims 4, but this project seems more expansive in scope (I never saw Song’s production). The relentless violence and chaos of GTA—its constant killing and mindless aggression—becomes an exhausting and repetitive obstacle to any final realization. It mirrors the challenge of staging any Hamlet itself, with all its historical and artistic heft (and “who would fardels bear?”).

The actor’s task—eventually Sam in this case—is akin to Hamlet’s own struggle. In his book, Acting Shakespeare, John Gielgud reflects on this affinity between the actor’s burden and Hamlet’s. And all of that is present here, even within the limited visual and non-bodily space of a video game, where VO speeches and dialogue must carry the weight.

By the end of Grand Theft Hamlet, scored by Jamie Perera, they manage a condensed performance of the play, and a lot of it is pulled off, not stopping till Hamlet’s “The rest is silence.”

There’s something comforting and eerily familiar about video game graphics—what Freud describes as the heimlich and unheimlich, the blend of homeliness and unhomeliness, the familiar turned strange. In that sense, video games, or the way these filmmakers manipulate this particular one, offer a promising tool for reworking canonical texts, which, like this, possess that same odd, comforting quality.

When a “straight” director takes on a “straight” adaptation of Hamlet, it often falls flat—David Tennant just isn’t Hamlet, neither is Laurence Olivier, or Kenneth Branagh, who lacks urgency. As American literary critic Harold Bloom once observed in one of his more unorthodox moments, Kurosawa’s Shakespeare films represent some of the best cinema to emerge from the plays. I’d say here, while GTA Hamlet isn’t aiming to be a definitive rendition of the tragedy, it serves as a reminder: if you approach Shakespeare head-on, without a sense of humor, or play, or attention to the shifting boundaries of self and culture, you won’t fully tap into what the text can offer.

Grylls and Crane manage to go beyond, blending the novel narrative potential of the video game space with the culturally ingrained plight of the Dane. And neither thing, game or Dane, remains the same afterward.

stills courtesy of Mubi

Grand Theft Hamlet

Project 1961 LTD and Grasp The Nettle LTD

90 mins | UK | 2024 | rated R

opens nationwide January 17, 2025

IG @ grandthefthamlet

X @ granthefthamlet (no “d”)