COME FOR THE MUSIC, STAY FOR THE CADILLAC

The music is everything in Miss Saigon’”not the plot, which is strangely muddled at times, and not the lyrics, which are sometimes awkward. What sticks in your mind and what made the show such an enduring hit (currently the eleventh longest running show in Broadway history) is Claude-Michel Schönberg’s gorgeous score. The show is based on Madame Butterfly, so the music is rightly influenced by Puccini, and then filtered through idioms of pop and musical theater. The lush score, whatever its manipulations or machinations, reaches out and rips at your heartstrings; it’s not content to merely tug at them.

Of the four productions of Miss Saigon I’ve seen since its Broadway premiere in 1991, the current one at La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts is hands down the most beautifully sung (perfectly aided by Julie Ferrin’s sound design). The voices are clear and distinctive, a difficult feat in the numbers where the chorus backs up the leads with intricate harmonies.

As Chris, the burned out soldier who finds love just as Saigon is about to fall, Kevin Odekirk has a lovely voice, and he doesn’t succumb to the urge of so many before him to make everything sound like a power ballad. He has power, yes, but it is tempered by a delicacy in the upper register and a control that gives the songs room to breathe. He doesn’t push. So his sorrow feels real, his bafflement at falling in love, genuine.

As Chris, the burned out soldier who finds love just as Saigon is about to fall, Kevin Odekirk has a lovely voice, and he doesn’t succumb to the urge of so many before him to make everything sound like a power ballad. He has power, yes, but it is tempered by a delicacy in the upper register and a control that gives the songs room to breathe. He doesn’t push. So his sorrow feels real, his bafflement at falling in love, genuine.

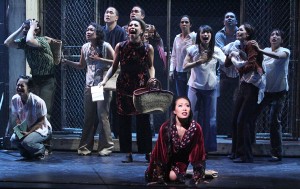

Kim is the seventeen year-old girl he falls in love with, newly arrived and coerced into prostitution at Dreamland, a Saigon bar that caters to soldiers on leave; every night there is a contest to crown “Miss Saigon,” after which a raffle-winner gets her for free. Jacqueline Nguyen sings the role with grace and intelligence, but her maturity, both in terms of her stage expertise and her ease with her own body, works against establishing her as a true babe in the woods who must learn to survive as the story progresses. Nguyen isn’t a girl thrown to the lions. She’s a woman who might just catch one of those lions and make a coat out of it.

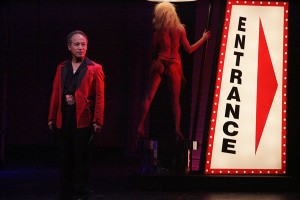

Then there is Joseph Anthony Foronda as the Engineer, the sleazy owner of Dreamland, who becomes a vital part of Kim’s story as she seeks some way of reuniting with Chris. He is always sweaty, on the make, boldly icky, and absolutely wonderful as he unctuously slinks across the stage. There’s something about his grasping, bouncy physicality that actually has you rooting for him at times (a far cry from the Tony-winning performance by Jonathan Pryce that stirred so much controversy in its day). The believably Asian Foronda, whatever his actual origins, is genuinely desperate for a visa to get into America. With Pryce there was never a sense of desperation, mainly since he is a pasty-faced Caucasian who seems about six and half feet tall. He wants to come to the USA? Fly into LAX. No one would give him a second look.

Then there is Joseph Anthony Foronda as the Engineer, the sleazy owner of Dreamland, who becomes a vital part of Kim’s story as she seeks some way of reuniting with Chris. He is always sweaty, on the make, boldly icky, and absolutely wonderful as he unctuously slinks across the stage. There’s something about his grasping, bouncy physicality that actually has you rooting for him at times (a far cry from the Tony-winning performance by Jonathan Pryce that stirred so much controversy in its day). The believably Asian Foronda, whatever his actual origins, is genuinely desperate for a visa to get into America. With Pryce there was never a sense of desperation, mainly since he is a pasty-faced Caucasian who seems about six and half feet tall. He wants to come to the USA? Fly into LAX. No one would give him a second look.

This takes me to the issue of race and Miss Saigon.

The 1991 controversy I speak of was over the fact that the Caucasian Pryce was cast in a Eurasian role. In London, he played the part with yellow makeup and prosthetics to make his eyes appear more Oriental. I use the politically incorrect term for Asian because the casting was viewed by many as insensitive and racist, no different than whites putting on blackface – something which is outlawed by Actors Equity of America. On stage, Pryce was forced by Equity to appear without makeup and prosthetics, and he looked ridiculous in the role. There were (and are) plenty of ethnic performers whose genetic cocktails make them believable as Asians’”and they get precious little opportunity to star in musicals.

This, in turn, takes me to the issue of race in this production of Miss Saigon.

I want to be color-blind when it comes to casting, and certainly when race has nothing to do with the plot, go for it. But Miss Saigon is about race differences. So when Kim’s spurned fiancé (Aidan Park), a Communist leader who was promised her hand at birth, is threatening violence because of his kinsmen’s traitorous support of Americans, it’s just weird to have his thugs be so clearly white.

In general, the ensemble is best in moments of stillness. In the ceremony that Kim counts as her wedding to Chris, the women’s voices are meltingly beautiful in their perfect blend, and the men’s voices rapturously soar in “Bui-Doi,” the number most blatantly calculated to bring you to tears. “Bui-Doi” is sung by Chris’ friend John (Lawrence Cummings) about the terrible plight of the mixed race offspring of white servicemen and Vietnamese women who have been left behind after the war, which is central to Chris and Kim’s story.

In general, the ensemble is best in moments of stillness. In the ceremony that Kim counts as her wedding to Chris, the women’s voices are meltingly beautiful in their perfect blend, and the men’s voices rapturously soar in “Bui-Doi,” the number most blatantly calculated to bring you to tears. “Bui-Doi” is sung by Chris’ friend John (Lawrence Cummings) about the terrible plight of the mixed race offspring of white servicemen and Vietnamese women who have been left behind after the war, which is central to Chris and Kim’s story.

The ensemble is less effective in the action numbers. The quasi-gymnastic-martial arts tumbling in “The Morning of the Dragon” is particularly awkward. Never mind that the performers lost their footing on their landings, they seemed dazed and unsure of what they were supposed to be doing. And in the Engineer’s big number “The American Dream,” once they enter, halfway through the song, they suck some of the energy out of Foronda’s gleeful ferocity.

There are two rather thankless roles in Miss Saigon. The first is Gigi (an exciting April Malina), the winner of the “Miss Saigon” pageant at Dreamland on Kim’s first night, who sings the first half of the poignant “The Movie in my Mind” which sort of echoes Fontine’s big number in Les Miserable (I have always thought of the number as “I Dream a Dream in Nam”). Then the character fades back into the chorus, which is a shame, as I wanted to see more of Malina.

There are two rather thankless roles in Miss Saigon. The first is Gigi (an exciting April Malina), the winner of the “Miss Saigon” pageant at Dreamland on Kim’s first night, who sings the first half of the poignant “The Movie in my Mind” which sort of echoes Fontine’s big number in Les Miserable (I have always thought of the number as “I Dream a Dream in Nam”). Then the character fades back into the chorus, which is a shame, as I wanted to see more of Malina.

The role of Ellen, Chris’s American wife, is a downer. In Miss Saigon, the plot’s momentum hinges on Ellen. Between the end of the war and Chris and Kim’s reunion three years later, Chris has returned to San Francisco; unable to find Kim in the chaos of Saigon’s transition to Ho Chi Min City, he gives up and finds love with Ellen. But his nightmares of the war and of Kim’s possible outcome stay with him.

Ellen has scenes and songs about how frightened she is of losing Chris and how determined she is not to let it happen. And we just don’t care. We want to see Kim and Chris back together, and when Ellen’s actions result in tragedy, the audience just hates her. Cassandra Murphy offers impressive vocals, but if there is a way of elevating the role to a point where you are on her side for even a moment, neither Murphy nor any other actress playing Ellen has found it.

Brian Kite directs with vigor, yet also with admirable restraint. When you have a show where prostitution is a key element, it’s easy to let things get over the top and vulgar, and it takes restraint to trust that whores will be whores and villains will be villains without overworking the tawdriness.

The production’s technical elements are not in the same class with the performances. Dustin J. Cardwell’s set pieces are particularly ill-conceived. They look flat, without dimension, and poorly created. The wood on the bedframe, for instance, looks like it was drawn in magic marker by a first grader. Steven Young’s lighting design is at its best when singling out individual performers and providing some marvelous backlighting, but too often in the group numbers, the ensemble goes murky. Mela Hoyt-Heydon’s costumes are a mixed bag. When the prostitutes are in attendance at Kim and Chris’ improvised wedding ceremony, their costumes are so similar, they look a bit like actual bridesmaids’”and however historically accurate, I’m not a fan of how clunky women look in wedged high heels, particularly when they are asked to dance.

The production’s technical elements are not in the same class with the performances. Dustin J. Cardwell’s set pieces are particularly ill-conceived. They look flat, without dimension, and poorly created. The wood on the bedframe, for instance, looks like it was drawn in magic marker by a first grader. Steven Young’s lighting design is at its best when singling out individual performers and providing some marvelous backlighting, but too often in the group numbers, the ensemble goes murky. Mela Hoyt-Heydon’s costumes are a mixed bag. When the prostitutes are in attendance at Kim and Chris’ improvised wedding ceremony, their costumes are so similar, they look a bit like actual bridesmaids’”and however historically accurate, I’m not a fan of how clunky women look in wedged high heels, particularly when they are asked to dance.

Then there is the helicopter.

No one expects multi-million dollar effects in La Mirada, but the main thrill of the original Broadway helicopter was its enhancement by a simple combination of a rotating light effect and a wind machine that made the helicopter blades seem real – an effective stage trick. Here, without any attempt at wind or blade motion, the helicopter just looks silly.

But at least they did give the Engineer his pink Cadillac in “The American Dream.” When he joyfully humps the hood of the car it strikes you as a kind of metaphor for the entire mess of the Vietnam War. Plus, it’s awfully engaging, as is this production of Miss Saigon. Whatever its flaws, it’s worth a look, and even more impressively, a listen.

But at least they did give the Engineer his pink Cadillac in “The American Dream.” When he joyfully humps the hood of the car it strikes you as a kind of metaphor for the entire mess of the Vietnam War. Plus, it’s awfully engaging, as is this production of Miss Saigon. Whatever its flaws, it’s worth a look, and even more impressively, a listen.

photos by Michael Lamont

Miss Saigon

La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts in La Mirada (Los Angeles Theater)

through May 6

for tickets, visit http://www.lamiradatheatre.com