THEATRE GHOST

In uncertain times such as these, audiences crave familiarity and nostalgia. Broadway, which once turned plays into movies, is now glutted with adaptations of popular films because it’s easier to sell a show as a known quantity based on a “title.” While producers play on our nostalgia, they usually diminish the source material, the result being a whole new canon of mediocre musical adaptations. It was expected, therefore, that the latest celluloid-to-stage entry, Ghost The Musical, would further perpetuate the art form’s devolution – and on paper, it does. The surprise is that spectators at the Lunt-Fontanne bear witness to the apotheosis of theater technology in Matthew Warchus’ tech-heavy production, which arrives via the West End. The downside of this production is that intimacy and detailed storytelling take a backseat to the stunning technology.

The 1990 film version of Ghost was an international success; the story of Sam, the ghost of a murdered man who can’t completely pass over until he makes the world safe for grieving girlfriend Molly, captured the imagination of a world processing the losses of the AIDS years. The film was an earnest blend of romance and spirituality, it won two Oscars (one for Bruce Joel Rubin’s screenplay and one for Whoopi Goldberg’s performance as reluctant psychic Oda Mae Brown), and it gave the Righteous Brothers’ “Unchained Melody” (written by Alex North and Hy Zaret) a second life due to a very sensual set piece involving Demi Moore, Patrick Swayze and a pottery wheel. Even though Ghost the movie already contained an iconic song, its larger-than-life characters and core love story made it perfectly viable source material for a Broadway musical.

The 1990 film version of Ghost was an international success; the story of Sam, the ghost of a murdered man who can’t completely pass over until he makes the world safe for grieving girlfriend Molly, captured the imagination of a world processing the losses of the AIDS years. The film was an earnest blend of romance and spirituality, it won two Oscars (one for Bruce Joel Rubin’s screenplay and one for Whoopi Goldberg’s performance as reluctant psychic Oda Mae Brown), and it gave the Righteous Brothers’ “Unchained Melody” (written by Alex North and Hy Zaret) a second life due to a very sensual set piece involving Demi Moore, Patrick Swayze and a pottery wheel. Even though Ghost the movie already contained an iconic song, its larger-than-life characters and core love story made it perfectly viable source material for a Broadway musical.

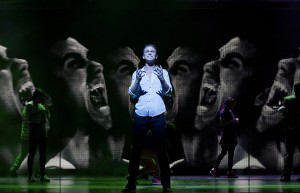

Two decades have passed since Ghost opened. Storytelling expectations have changed due to advances in technology. Warchus’ production acknowledges this, and the result is a show full of dazzling special effects. From the first look at the show curtain with its Manhattan landscape and the subtly glowing, flowing waters of the Hudson, Warchus lets his audience know not to expect business as usual. The cinematic tricks in the film (walking through walls, souls leaving bodies, and putting hands through objects) today translate more easily onto the stage. Warchus works brilliantly with his design team to create a vibrant world of color, movement, and legerdemain. John Driscoll’s video projections work seamlessly with Rob Howell’s open, three-walled set design as apartments become hospital rooms, and then offices, in the blink of a new projection. Add Paul Kieve’s work as an illusionist, and the audience is given a generous serving of “how did they do that” moments. The technical side of the show is so advanced that it’s easy to take normal theatrical details for granted – like Hugh Vastone’s flawless lighting design. All of the tech aspects gloriously come together on a subway car where Sam discovers the aerodynamic rules of his new world; that set piece is as brilliant a spectacle as anything you’re likely to see on Broadway this season.

Two decades have passed since Ghost opened. Storytelling expectations have changed due to advances in technology. Warchus’ production acknowledges this, and the result is a show full of dazzling special effects. From the first look at the show curtain with its Manhattan landscape and the subtly glowing, flowing waters of the Hudson, Warchus lets his audience know not to expect business as usual. The cinematic tricks in the film (walking through walls, souls leaving bodies, and putting hands through objects) today translate more easily onto the stage. Warchus works brilliantly with his design team to create a vibrant world of color, movement, and legerdemain. John Driscoll’s video projections work seamlessly with Rob Howell’s open, three-walled set design as apartments become hospital rooms, and then offices, in the blink of a new projection. Add Paul Kieve’s work as an illusionist, and the audience is given a generous serving of “how did they do that” moments. The technical side of the show is so advanced that it’s easy to take normal theatrical details for granted – like Hugh Vastone’s flawless lighting design. All of the tech aspects gloriously come together on a subway car where Sam discovers the aerodynamic rules of his new world; that set piece is as brilliant a spectacle as anything you’re likely to see on Broadway this season.

However, there is a price to be paid for such tech-savvy art. Driscoll occasionally projects extreme close-ups of the leads, but they come across as glossy magazine prints from a PowerPoint presentation, and do nothing to inform the moment. Compounding this, much of Ashley Wallen’s choreography is closer to Solid Gold than a gold standard, and the production numbers often seem like theatre trapped in an MTV video. Moreover, human dancers can’t realistically hope to compete with giant projected images of themselves.

However, there is a price to be paid for such tech-savvy art. Driscoll occasionally projects extreme close-ups of the leads, but they come across as glossy magazine prints from a PowerPoint presentation, and do nothing to inform the moment. Compounding this, much of Ashley Wallen’s choreography is closer to Solid Gold than a gold standard, and the production numbers often seem like theatre trapped in an MTV video. Moreover, human dancers can’t realistically hope to compete with giant projected images of themselves.

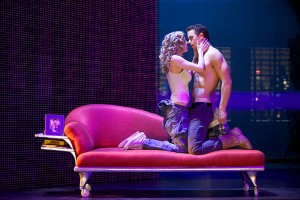

The principal performers do their best to rise to the occasion, portraying their roles competently, and in some cases exceptionally. Like Whoopi Goldberg, Da’Vine Joy Randolph steals every scene she is in as Oda Mae Brown, the fake psychic who discovers she has real paranormal gifts. Randolph fearlessly embraces Oda Mae’s broader strokes to provide necessary comic balance between scenes that are otherwise about death, mourning, and financial fraud. Richard Fleeshman does solid work as Sam, leading with his strong pop belt, repeating his role from the original West End production. He is a handsome, charismatic, and winning Sam. Less successful is Caissie Levy as the grieving artist Molly: although Levy intelligently offers more upbeat colors to the character (unlike Demi Moore’s melancholy turn in the film), she lacks the star quality to fill a Broadway house. Rounding out the cast is Bryce Pinkham in the thankless role of Carl, Sam’s smarmy, good-looking friend; Pinkham exudes both qualities very well.

The principal performers do their best to rise to the occasion, portraying their roles competently, and in some cases exceptionally. Like Whoopi Goldberg, Da’Vine Joy Randolph steals every scene she is in as Oda Mae Brown, the fake psychic who discovers she has real paranormal gifts. Randolph fearlessly embraces Oda Mae’s broader strokes to provide necessary comic balance between scenes that are otherwise about death, mourning, and financial fraud. Richard Fleeshman does solid work as Sam, leading with his strong pop belt, repeating his role from the original West End production. He is a handsome, charismatic, and winning Sam. Less successful is Caissie Levy as the grieving artist Molly: although Levy intelligently offers more upbeat colors to the character (unlike Demi Moore’s melancholy turn in the film), she lacks the star quality to fill a Broadway house. Rounding out the cast is Bryce Pinkham in the thankless role of Carl, Sam’s smarmy, good-looking friend; Pinkham exudes both qualities very well.

Ghost the Musical’s biggest shortcoming is the book and score. None of the writing team has much musical theatre experience, and it unfortunately shows. The music is mostly of the generic pop song variety, written by the collaborative team of Dave Stewart (half of the Eurythmics), Grammy-winner Glen Ballard, and Oscar-winning scribe Bruce Joel Rubin. They make the predictable mistakes of first time musical theatre writing teams: Song placement is not based on emotional peaks, but rather on intellectual ideas; recitative numbers deflate the conflict of a scene when tension should be building; and they give Molly an overly long Act One ballad that clearly belongs in Act Two.

Ghost the Musical’s biggest shortcoming is the book and score. None of the writing team has much musical theatre experience, and it unfortunately shows. The music is mostly of the generic pop song variety, written by the collaborative team of Dave Stewart (half of the Eurythmics), Grammy-winner Glen Ballard, and Oscar-winning scribe Bruce Joel Rubin. They make the predictable mistakes of first time musical theatre writing teams: Song placement is not based on emotional peaks, but rather on intellectual ideas; recitative numbers deflate the conflict of a scene when tension should be building; and they give Molly an overly long Act One ballad that clearly belongs in Act Two.

The songs rarely move the plot forward, and the lyrics are forgettable. It is a bad sign that “Unchained Melody” is the musical highlight of Act One; worse yet, the audience is relieved and grateful when it reprises in Act Two. Rubin (credited as the sole author of the book) faithfully follows his screenplay with the exception of the famous pottery scene: The film script used the potter’s wheel beautifully to reveal the intimacy in Molly and Sam’s relationship while he was alive; Rubin’s restructured libretto treats it as a memory piece in Act Two, thereby wasting an opportunity to develop Sam and Molly’s relationship, and proving that the strengths of this production are not in the writing.

The songs rarely move the plot forward, and the lyrics are forgettable. It is a bad sign that “Unchained Melody” is the musical highlight of Act One; worse yet, the audience is relieved and grateful when it reprises in Act Two. Rubin (credited as the sole author of the book) faithfully follows his screenplay with the exception of the famous pottery scene: The film script used the potter’s wheel beautifully to reveal the intimacy in Molly and Sam’s relationship while he was alive; Rubin’s restructured libretto treats it as a memory piece in Act Two, thereby wasting an opportunity to develop Sam and Molly’s relationship, and proving that the strengths of this production are not in the writing.

In the twenty years since the movie was released, stories themselves haven’t changed, but how we can tell them has. Ghost The Musical is the rare Broadway production where the adaptation might actually have enhanced a beloved older film and made it more accessible to the next generation, using state-of-the-art technology to shed new light on an old chestnut. Instead, Warchus’ production is designed for the ADD generation, moving so fast that you might need your Dramamine.

In the twenty years since the movie was released, stories themselves haven’t changed, but how we can tell them has. Ghost The Musical is the rare Broadway production where the adaptation might actually have enhanced a beloved older film and made it more accessible to the next generation, using state-of-the-art technology to shed new light on an old chestnut. Instead, Warchus’ production is designed for the ADD generation, moving so fast that you might need your Dramamine.

Photos by Sean Ebsworth Barnes and Joan Marcus

Ghost The Musical

Lunt-Fontanne Theatre in New York City

Open Run

for tickets, visit http://www.ghostonbroadway.com/tickets/