WHEN A SCRIPT IS NOT COMMENSURATE WITH ACTOR

There are two compelling reasons to see Laurence Fishburne portray Justice Thurgood Marshall in Thurgood, a transplanted production currently running at the Geffen Playhouse: one is its subject matter, Thurgood Marshall, and the other is the actor who plays him, Laurence Fishburne.

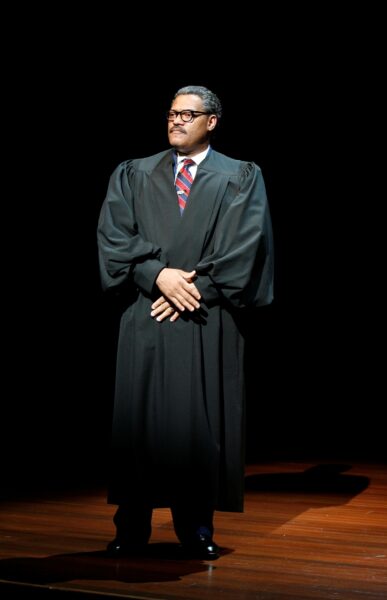

Mr. Fishburne is a towering, commanding, charismatic presence, and Los Angeles is privileged to have the opportunity to witness this remarkable theatre actor up close (Fishburne is perhaps best known to film audiences as Morpheus from the The Matrix series).

Marshall, if you’re not up on U.S. History, is one of the greatest figures of 20th-century law and civil rights; he is the first Black person to serve on the Supreme Court and his list of accomplishments is stunning. You will learn many fascinating facts, and even be inspired by the Great Man in this solo show/history lesson. You are guaranteed a great actor and a great subject, great dialogue (courtesy of Thurgood Marshall himself), and a very good theatrical event.

But not a great play.

Discerning theatergoers can decide if they are willing to look past a poorly constructed script by George Stevens, Jr., who clearly knows his subject well: Stevens was the writer/director of Separate But Equal, the miniseries about the Brown vs. Board of Education school desegregation case on which Marshall was the lawyer for the NAACP before the Supreme Court.

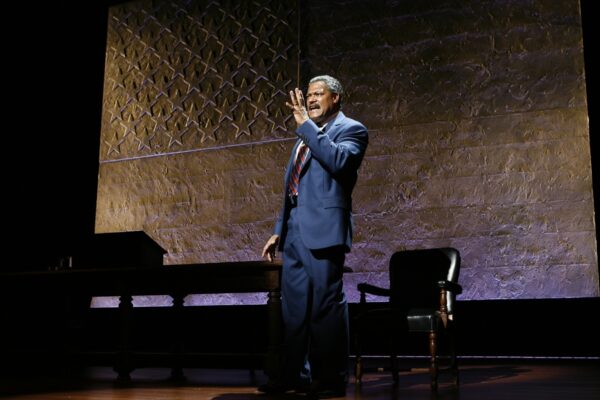

Stevens falls into the implicitly dangerous trap of a biographical one-person show: it becomes about the subject’s lifetime list of events in lieu of an actual plot. No matter how compelling each individual account is, the show’s form feels repetitive: “And then I…,” “And then I…,” “And then I…” Although Mr. Fishburne embodies the oratorical wizard flawlessly, the result is an on-again, off-again (albeit stunning) lecture; an amazing feat for a seminar, but somehow inconsequential for the theatre.

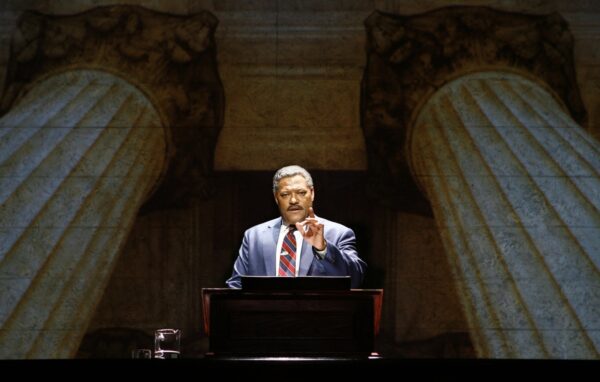

Indeed, the show begins with an aged and limping Thurgood addressing us, the Howard University student body, with what will prove to be the highlight of the evening: the familial history which leads us to his decision to become a lawyer. When Thurgood, a descendant of slaves, reveals the nomenclature of his relatives’ names, it is not only entertaining, but works because we receive insight into the creation of such a towering figure. Later in the show, such insight is scarce. I would love for the playwright to let us know why, for instance, Mr. Marshall would have been so relentless in his pursuit of civil rights that he was in absentia from his wife 200 days out of the year – and not just that he was.

I cringed when the playwright had his Thurgood invite the audience to shout out responses to his questions (David Rambo’s Ann Landers in his play The Lady with All the Answers tried this at the Pasadena Playhouse to embarrassing results); but – surprise! – it actually worked. I, myself, shouted out, “Plessy versus Ferguson!” referring to the case which established Jim Crow laws. No sooner had this permissive dialogue between great man and student body been established, however, than the device was dropped and never used again.

Some may look past such blatant incongruity because the star and subject of the show are so intriguing, but I found it somewhat troubling, especially the lack of clarity in regards to the audience’s relationship to Thurgood. Not long into the show, Thurgood’s cane is set aside and Fishburne youths up as he begins recounting tales of yore; but who is he talking to? Is it the student body or is he just having a 90-minute senior moment?

The triumphant verdict in Brown vs. Board of Education, though thrillingly reenacted by Fishburne and a voiceover, is not itself a thrilling moment, thanks to the disengaged narrative. In fact, even though we hardily applaud the court’s decision, the energy in the house is oddly flat; largely because we have been plopped down in this moment in history, and have not been given the opportunity to attach ourselves to Thurgood’s soul via a thrilling exposition; instead of theatrical electricity, we are left with a powerful yet emotionally inconsequential reminiscence.

When Thurgood speaks of his close relations to Langston Hughes, Kennedy, and LBJ, the almost unperceivable personal history an American can acquire is extraordinary to hear about, but the script’s awkward storyline rears itself when Thurgood mentions the passing of his wife, Buster; it feels like a sidebar in a magazine article, and we lose what may have been a most impactful moment.

Leonard Foglia’s direction is serviceable and certainly he must be credited with the assemblage of a proficient technical team. Allen Moyer has constructed a giant, stucco-like U.S. flag onto which Elaine J. McCarthy’s inventive projections bring us ever closer to the great litigator’s surroundings. Brian Nason’s lights are sharp, tight and creative. Ryan Rumery’s superlative stereo sound is so authentic that I found my head whipping around behind me to see whose cell phone sounded like a gavel. Most impressive are the precise cues called by Stage Manager James T. McDermott.

And so Thurgood is like watching waves upon a shore: one crashes decisively, then a few gently lap, then a medium size, then a huge wave again that shakes us out of the meditative state that the playwright’s construction creates. Pity the audiences of future productions of Thurgood which are not graced with Laurence Fishburne’s presence; he is the reason it doesn’t sink.

photos by Carol Rosegg

Thurgood

Geffen Playhouse, 10886 Le Conte Ave. in Westwood

ends on August 8, 2010

for tickets, call 310.208.5454 or visit Geffen Playhouse