IN PURSUIT OF DRAMA

Beneath the stairwell sign assuring guests that all cigarettes smoked on stage are herbal, the following sign might as well have been posted regarding The Roundabout’s new production of Simon Gray’s The Common Pursuit: “Please rest assured that even the most profound dialogue in this play contains nothing that might cause anxiety, moral discomfort, sadness, painful self-reflection, spiritual restlessness, or any other sort of emotional turbulence.”

The Common Pursuit, first performed in 1984 in a production directed by Harold Pinter, tells the story of six friends over a twenty year period. We first meet them as sophomores at Cambridge, in the rooms of Stuart Thorne (played energetically by Josh Cooke). Stuart is an idealistic young man full of excitement and optimism for both his beautiful girlfriend Marigold Watson (Kristen Bush), with whom he is madly in love, and “The Common Pursuit,” an uncompromisingly highbrow literary magazine, which he is in the process of launching. To help with the magazine, Stuart has invited to his rooms four undergraduate acquaintances, each of whom has his own literary ambitions.

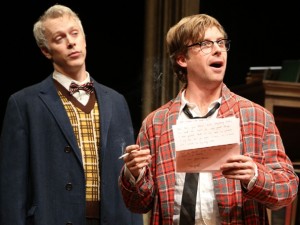

The young men are Peter Whetworth (Kieran Campion), a self-declared scholar in history who is known as Captain Marvel because of the way he handles the ladies; Martin Musgrove (Jacob Fishel), who admits to having no talent at all but who wants to work on the business side of publishing; Humphry Taylor (Tim McGeever), a poet and philosopher with a dry wit and keen powers of perception; and Nick Finchling (the enjoyable Lucas Near-Verbrugghe), a droll, impish souse, with ambitions to be the Sunday Times theater critic. All five young men are brave and confident, anxious to set sail on the ocean of life. But when we next encounter this group, nine years later, we discover that their respective voyages haven’t exactly proceeded as planned.

The young men are Peter Whetworth (Kieran Campion), a self-declared scholar in history who is known as Captain Marvel because of the way he handles the ladies; Martin Musgrove (Jacob Fishel), who admits to having no talent at all but who wants to work on the business side of publishing; Humphry Taylor (Tim McGeever), a poet and philosopher with a dry wit and keen powers of perception; and Nick Finchling (the enjoyable Lucas Near-Verbrugghe), a droll, impish souse, with ambitions to be the Sunday Times theater critic. All five young men are brave and confident, anxious to set sail on the ocean of life. But when we next encounter this group, nine years later, we discover that their respective voyages haven’t exactly proceeded as planned.

Ostensibly, Mr. Gray’s play, adequately directed by Moisés Kaufman, is about how the realities of adult life chip away at the noble aspirations of our youth, forcing us to make moral and artistic compromises, undermining our high ideals and corrupting those things most precious to us. In fact, what The Common Pursuit truly offers is clever and witty dialogue, humorous quips about the humanities, and a lot of inside jokes about Cambridge and other things British.

Ostensibly, Mr. Gray’s play, adequately directed by Moisés Kaufman, is about how the realities of adult life chip away at the noble aspirations of our youth, forcing us to make moral and artistic compromises, undermining our high ideals and corrupting those things most precious to us. In fact, what The Common Pursuit truly offers is clever and witty dialogue, humorous quips about the humanities, and a lot of inside jokes about Cambridge and other things British.

To be fair, some of what is said is quite excellent, even profound. Here is an excerpt, where Humphry explains to Martin why he’s abandoned writing his book on Wagner:

“…I’ve got the scholarship, and the judgment, but not the imagination to understand him. Him in relation to his music. Everything I’ve written about him reduces him to my own sort of size. Which makes him too small to be interesting to me. You see, I’ve discovered I have a slight flaw after all. Moral, I think, rather than intellectual. I diminish what I most admire.”

Elsewhere, when it is suggested that he might live longer if he quits smoking, Nick’s witty retort is “Oh, you don’t live longer, it just seems longer.”

I expect one’s enjoyment of The Common Pursuit is very much contingent on the extent to which one enjoys crafty speech, and on whether the satisfaction of listening to it outweighs the disappointing dramatics of the play, as well as the somewhat superficial though not unentertaining performances.

The play is divided into four scenes (plus an epilogue), with each scene taking place some years after the previous one. Considerable drama happens in the intervals between these scenes: a violent death, an awful betrayal, humiliating compromises, adultery, impotency, forbidden love. Unfortunately, none of it happens on stage. Instead, we are told about these events by the characters after the fact. It’s as though the play was written specifically to exclude dramatic moments, to exclude suspense. Without seeing characters take action in dealing with obstacles, we have little by which to define them; consequently, we never have any real empathy for them – perhaps symbolic and intellectual empathy, but nothing that drills its way into our being on a visceral level. In addition to which, these off-stage events, happening as they do of their own accord (they just seem to fall out of the sky) are dramatically and artistically meaningless, much like the pointless facts rattled off about a character’s back story in a soap opera. As for the three or so dramatic moments that do take place before us, these are predictable and neither important nor revelatory.

The play is divided into four scenes (plus an epilogue), with each scene taking place some years after the previous one. Considerable drama happens in the intervals between these scenes: a violent death, an awful betrayal, humiliating compromises, adultery, impotency, forbidden love. Unfortunately, none of it happens on stage. Instead, we are told about these events by the characters after the fact. It’s as though the play was written specifically to exclude dramatic moments, to exclude suspense. Without seeing characters take action in dealing with obstacles, we have little by which to define them; consequently, we never have any real empathy for them – perhaps symbolic and intellectual empathy, but nothing that drills its way into our being on a visceral level. In addition to which, these off-stage events, happening as they do of their own accord (they just seem to fall out of the sky) are dramatically and artistically meaningless, much like the pointless facts rattled off about a character’s back story in a soap opera. As for the three or so dramatic moments that do take place before us, these are predictable and neither important nor revelatory.

The whole play is like one long set up without a punch line; it is a statement. Perhaps that was the intent. But then, as statements go, it’s a fairly banal and obvious one: Practical concerns corrupt high ideals, the public values sensationalism over serious art, love gets lost, friends betray you, your body betrays you, and the guy you suspected was gay is actually screwing your wife – now, here is some witty English banter to tide you over for the next two hours.

The whole play is like one long set up without a punch line; it is a statement. Perhaps that was the intent. But then, as statements go, it’s a fairly banal and obvious one: Practical concerns corrupt high ideals, the public values sensationalism over serious art, love gets lost, friends betray you, your body betrays you, and the guy you suspected was gay is actually screwing your wife – now, here is some witty English banter to tide you over for the next two hours.

It’s not easy to write clever dialogue. But it’s much more difficult to write character-defining drama, the lack of which, I believe, is the ultimate problem with this play and with this production. Maybe there is some ingenious way to make The Common Pursuit work, but in this production Mr. Kaufman and his actors failed to find it.

It’s not easy to write clever dialogue. But it’s much more difficult to write character-defining drama, the lack of which, I believe, is the ultimate problem with this play and with this production. Maybe there is some ingenious way to make The Common Pursuit work, but in this production Mr. Kaufman and his actors failed to find it.

photos by Joan Marcus

The Common Pursuit

Presented by Roundabout Theatre Company at The Laura Pels Theatre in the Harold and Miriam Steinberg Center for Theatre in New York City

scheduled to end on July 29, 2012

for tickets, visit http://www.roundabouttheatre.org/