WHAT’S YOUR STORY?

In the “It’s Not the Story, It’s in How You Tell It” Department, an incredible number of shows I saw in the last month have incredible tales to tell, but falter in their context. Listen, storytelling is in our genes ever since cavemen told their friends how they caught a mammoth. From mythology to everyday gossiping, stories are an intricate part of our lives. But a good story in the theater — whether Aristophanes or Shakespeare to Neil Simon — playwrights and directors need to create a vivid, immersive experience that resonates with the viewers. Could it be that in our world of an ever-spinning nightmare of information we are actually losing the art of storytelling?

Certainly the most egregious was Pasadena Playhouse‘s La Cage aux Folles, a sure-fire winner of a musical dashed upon the rocks of inclusion. Director Sam Pinkleton (of Broadway’s Oh, Mary!, a stupid show whose success boggles the mind) amassed Broadway’s best designers and the great Cheyenne Jackson to offer the ugliest sets and costumes on record, uneven performances, and some damn annoying singing (as Albin, the grating Kevin Cahoon sounded like the love child of Megan Mullally and Pennywise the Clown from IT), all in the name of diversity. If you’re gong to cast an actor with a disability, another who is plus-sized, another transgender, all different races and sizes, then by-God they should at least be in service to the material, not just their existence. What a hot mess. Check out my colleague’s review here. Runs through December 15, 2024.

Cody Brunelle-Potter, Ellen Soraya Nikbakht, Salina EsTitties, Kay Bebe Queue, Paul Vogt as Les Cagelles in La Cage aux Folles at Pasadena Playhouse (photo by Jeff Lorch)

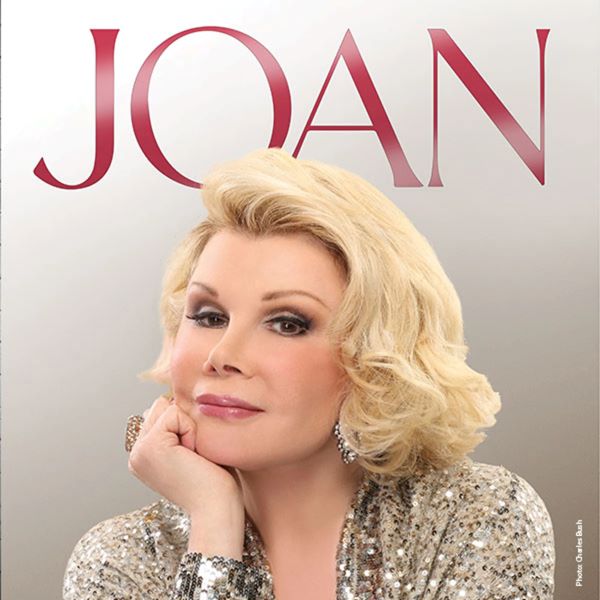

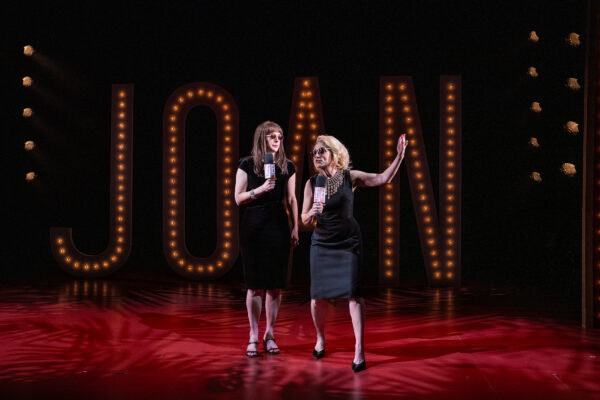

Over at South Coast Rep, Tessa Auberjonois gives us a cracking good Joan Rivers in the new bio-play about the comedienne by Daniel Goldstein, directed by David Ivers. Joan is one of the most original Americans on record (and a basis for The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel), so capturing her life in a one-act is like, as they say, putting lightning in a bottle. This four-hander has actors, including Auberjonois, doing double-duty as characters from Joan’s life. We skim past the early years of the blunt, contentious and hysterical performer when she seemed destined to be the wife of some rich Upper West Side doctor (Auberjonois is so good as Joan’s mom, Mrs. Molinsky, that I was sad to see the character disappear from view after one scene). A young Joan is played by Elinor Gunn, who — in Kish Finnegan’s incredible wig — is also Rivers’ daughter Melissa, who in real life not only gave full blessing for this world premiere, but commissioned it. Melissa has scenes with Joan but is also used as a narrator — a good idea because Melissa is the best first-hand witness to Joan’s life, but a bad idea because Melissa is simply not an interesting character (nor in real life was she interesting being a co-commentator with her mom about fashion on the runway of TV Awards shows).

A good chunk of the spotty play goes to the story of Joan and her husband, Edgar (a shapeshifting Andrew Borba), who produced Joan’s first-ever talk show of her own on Fox TV, something Johnny Carson never forgave her for since she was already the permanent guest host on the Tonight Show. After one year of her show, the Fox network said that either Edgar goes or the show goes — Joan sided with her husband, who would not long thereafter commit suicide. Zachary Prince later does a killer Jimmy Fallon interviewing Joan on his Tonight Show after her 26-year ban, when she said, “The Germans killed six million Jews, you can’t fix a fucking carburetor?” “Welcome back to the network,” Fallon said.

Tessa Auberjonois (Joan) and Zachary Prince (Jimmy Fallon). Photo © Scott Smeltzer

But in trying to cover Joan A to Z, Goldstein ends up with a scrapbook as play. I never really felt like I got to know the actual Joan. Sometimes funny (how could it not be using Joan’s material?), the storytelling is an annotated overview, skipping decades at a time, which turns out to be a distancing way to honor Joan’s legacy. It plays through November 24.

At the Zephyr Theatre, Chromolume Theatre finally returns. This is the company that presented a storefront theater version of Pacific Overtures at The Attic, a miraculous outing that brought Sondheim’s masterpiece to vivid life. As with Chicago’s many many storefront theaters, Chromolume’s goal is to offer rarely produced musicals, and promises a Sondheim show each season. Well, we’re going to have to wait for later when Passion will be produced, because their first outing, Blind Date (which is far from rarely produced), is — and it breaks my heart to say this — an amateur production at best.

First Date is an enjoyable 2012 musical comedy that opened on Broadway in 2013. It should really be called Blind Date, as its two principal protagonists, awkward Aaron (Troy Dailey) and artsy Casey (Paloma Malfavón), have never met before. They’ve been set up on a dinner date by friends. Aaron’s still trying to get over his ex-girlfriend Allison, while Casey has a spiky personality that sends men scurrying. Rather predictably, and with lots of rom-com clichés and pop culture references dotting the way, the two happily form a connection.

First Date is a fairly focused and light-hearted look at a dating culture that is fast disappearing in the face of quick hookups fueled by free apps. Austin Winsberg’s one-act book, along with Alan Zachary and Michael Weiner’s music and lyrics, provides more of a celebration than a critique of first date mythology. We witness Aaron and Casey trying to make small talk, agonizing over what to order, fighting for the check, etc., all punctuated by song and dance numbers reminiscent of Glee and High School Musical. There are five supporting cast members that each play numerous characters, including Casey’s gay best friend Reggie (Christopher Baker), who calls Casey throughout the night to give her an out if she needs to ditch her date, and Aaron’s Grandma Ida (Bonnie Joy Sludikoff), who appears when we learn that Casey is a shiksa.

Some cute stuff. But director James Esposito could not correct the lousy acoustics at The Zephyr, with a crazy amount of lines lost in the tiny space. The main couple is at a table upstage with supporting players taking the focus downstage, when it should have been the other way around. And while I admired that voices were distinct, the cast just didn’t gel as a unit and half the cast couldn’t project past the first row, and one is not a great actor. Esposito keeps the action moving — a bit too much as actors should have focused on singing — but with unseasoned performances that go all over the map, the simple story gets lost.

As a critic, I tend to avoid one-person shows. They are usually overly focused on a single perspective, self-indulgent, and can feel repetitive due to the single performer carrying the entire narrative. Plus, with the cost of putting on shows, they’re sprouting up all over the country. People can actually make a living traveling from Fringe to Fringe from Australia to Edinburgh, and what they all want reviews to promote their show. I’ve seen some fine displays of talent at The Hollywood Fringe and elsewhere, but while the stories are compelling, a stream-of-consciousness about “My mother was a hoarder” or “I came out on a submarine” can be exhausting. And the problem is rarely the performer, it’s the play and the way they tell it.

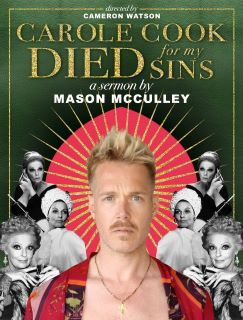

Mason McCulley in Carole Cooke Died for My Sins. Photo by Jeff Lorch

Over at the Skylight Theatre is writer/performer Mason McCulley, an attractive affable endearing fellow who, after the death of his mom and his friend, the great comedienne Carole Cook, goes through a spiritual crisis that ultimately leads to his being sober. McCulley covers a lot of ground, from tricks to drinking benders to a detailed analysis of his impermanent, objective-free lifestyle. There are effective, vivid sequences in which McCulley has an a-ha! moment, but because of the show’s bloated budget (he got the best designers in town) it takes a while to realize that the play — even with the cunning hand of director Cameron Watson — has the shape of an amoeba. Told out of chronological order on a lavish set, I couldn’t figure out what the main takeaway was. So it ends up basically a stream-of-consciousness A.A. meeting one-man fringe show with nowhere to go. I mean I get it, the show is subtitled a sermon, so you can expect an exhortation, especially on a moral issue, but it shouldn’t end up feeling long and tedious. It plays through November 24, 2024.

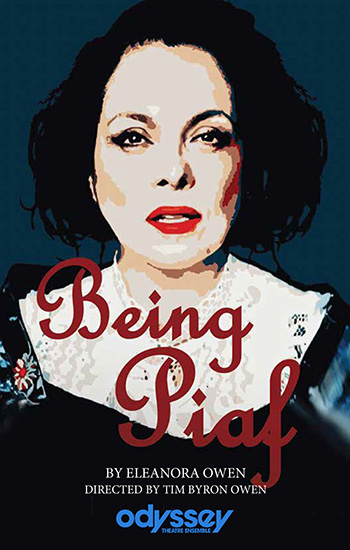

Speaking of one-person shows, Being Piaf, written and performed by Eleanora Owen at the Odyssey Theatre, is a play about the talented and tragic chanteuse Edith Piaf. Known for her torch ballads, cabaret style and songs of love and sorrow, this French artist got her start on the streets of Paris in the 1940s as a street artist trying to earn money. She graduated to brothels and nightclubs, ultimately singing with the Paris Olympia music hall. In America, she became famous in the late 1950s, appearing on The Ed Sullivan Show eight times. Struggling with alcoholism and drug use her whole life, she died at age 47 of liver cancer.

Eleanora Owen in Being Piaf (Photo by Doug Engalla)

Instead of channeling a performance for us at a club, a la Billie Holiday in Lady Day at Emerson’s Bar & Grill, Owen — who has the Piaf look down pat — places us on a street corner late in Piaf’s life. Relating depressing incident after depressing incident — barely skimming over her success — Owen asks names of people in the audience, and at one point stared at me with a look that I can only describe as some crazy hatchet murderess from a maze at Knott’s Scary Farm. Owen has pipes, but she delivers the songs as if she were starring in an operetta, with absolutely no drama or sorrow in her voice. Because Owen doesn’t even attempt to sound like Piaf, this feels like a showcase directed like a Fringe entry. Making up the entire set is a streetlamp and café table from which she empties almost an entire bottle of wine, but never gets drunk. If she is on a street corner talking to us, why does a karaoke soundtrack come on with a string section? I’m like, what street corner are we on?! The audience was full of friends and her director husband Tim Byron Owen who screamed “Bravo” after every song. This is no way to celebrate one of the most celebrated singers of the 20th century. Closed. Played six performances.

Ah, Rent, Jonathan Larson’s 1996 WAY-overproduced musical was revived by Jaxx Theatricals of Chess fame in their intimate space for nine performances, but the company (which has already produced Rent before) concentrates on volume more than story — and it’s an imperfect musical to begin with. Near the beginning of its 12-year-run on Broadway, a film producer walked up to me at intermission and asked, “Do you think it’ll make a good movie?” “I’m still trying to figure out if it’s a good musical,” I answered. And I re-discovered watching Jaxx’s revival exactly how this musical can and still could be tightened. But with Larson’s death the day before the musical’s first preview performance Off-Off-Broadway, the musical remains unchanged (as Sondheim said, “A work in progress frozen in time”) — as is that dull film version. Revival after revival after revival and all those tours keep going based on its fame and its groundbreaking treatment of people with AIDS, queers, and the disenfranchised denizens of the East Village scene.

The Cast of Rent (photo by Corran Villalobos)

The Cast of Rent (photo by Corran Villalobos)It’s amazing that an earnest, energetic, enthusiastic ensemble doesn’t spontaneously combust navigating the tiny playing area between viewers on both sides in an alley theater configuration — a remarkable feat while executing the large crowd scenes and tight choreography. So why with this sprawling well-cast ensemble (Jabari simply glowed as the generous drag queen, Angel) should I be thinking about the musical’s imperfections instead of listening to the songs? Because it goes for big when confidential was called for. Plus, we are given actors with face mikes competing with an overly loud band ensuring that — what? — about 50% of the lyrics are dashed to the fiery pits of musical hell. This is precisely the kind of space where actors should be concentrating on character and wailing to us without mikes, accompanied by a piano and guitar for a truly Bohemian sound. Closed. Rent played nine performance.

In A Going Away Party Play at Boston Court, playwright Keyanna Khatiblou has a persuasive story to tell about her Welsh mother and Iranian father who were living in Iran at the time of the Revolution. There are some truly harrowing scenes in which Khatiblue recreates her family history as her pregnant mom and stalwart dad have moved to Iran, her father’s birthplace, so he could serve in the military for two years in order to work for the American company that recruited him. It’s a stressful situation with her mom working a job speaking in English, while living with her husband’s mother and pro-revolution, lesbian sister adds to the drama.

A Going Away Party Play (photos by Brian Hashimoto)

And yet these awesome scenes are couched in an odd, cutesy children’s theater-like night of party games with friends of the playwright (written as a character named “Mina”), who can’t figure out how she fits in America during the Trump-era. Conveniently, her friends are a European-American, an Iranian-American, a gay-Latino-American and a Korean-American, who address the audience directly (yuck!) to make a PC point about different people and cultures and their thoughts about freedom. In trying to salute multi-culturalism in the U.S., she diffuses her story. Instead of leaving the theater devastated about what some people go through to find freedom from authoritarian regimes, I left thinking about whiny people who are frustrated that the American Dream is really a myth. Closed. Played 13 performances.