AN EVERY LITTLE THING OF BEAUTY

The most amazing thing about the recurring slow-motion sequences of hovering hummingbirds in Every Little Thing is the stillness of their tiny heads, even as their wings flap and their little bodies shift in air. As Terry Masear tells us, among other remarkable things, the wings of a hummingbird flap fifty times per second. She rightly asks, how can you know this and not tap into some magical realism? It might be said that those who do tap into magical realism in our world have much of it in themselves. This would apply to Terry, herself quite magical, one of those extraordinary people who actually devote their lives to what other people can only think about doing.

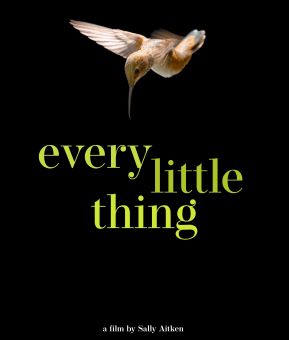

Every Little Thing, directed by Sally Aitken, and opening January 10, 2025 (NY) and January 17 (LA), seeks to awaken our attention to the kind of divine evanescence and moment-to-moment splendor embodied by hummingbirds themselves. Appreciation for the present moment, Terry claims, is one of the greatest lessons humans can learn from any animal.

Terry Masear is the ideal documentary subject; solitary, knowledgeable, obsessive, eccentric, she is passionate and well-equipped in carrying out her project of rescuing and recuperating every injured or ill hummingbird she comes across in the city of Los Angeles. She lives in a gorgeous home, the outdoor space of which she has converted into a rehabilitative paradise for injured hummingbirds. In addition to the hummingbirds she finds are those brought to her attention by any who make use of her know-how and gentle skill. The scenes of Terry fielding phone calls from seemingly anyone with hummingbird-related issues are strangely compelling; at one point she resolves from afar the minor catastrophe of one trapped in a skylight. The man involved in that incident is interviewed in the documentary, and spoke of “the life-force” of the hummingbird he’d freed, an idiom which serves to remind us we are, after all, in Los Angeles.

Though Terry helps people, and we even witness a friendly visitation from a young woman with injured baby hummingbirds, which Terry immediately sets about healing, tipping a tiny pump into the tiny mouths of these tiny marvels, she can also be unforgiving in her critique of human selfishness. When she is given a hummingbird whose temporary owners damaged its wing by dumping sugar water on it, Terry convincingly argues that this behavior reflects a broader attitude of arrogant disregard for nature. The feeling that hummingbirds are ours to be mishandled is a statement about nature at large which Terry rightfully refuses to tolerate.

As Terry is a rich subject, so our inevitable curiosities about her backstory are steadily and unobtrusively satisfied by director and writer Sally Aitken (Playing With Sharks), who intersperses a straightforward presentation of interviews and scenes with her subject, with the aforementioned slow-motion majesty of fluttering hummingbirds, or in communion with flowers and dew-dropleted branches, accompanied by Caitlin Yeo‘s sensitive score (wildlife cinematographer Ann Prum). The hummingbird very clearly belongs to nature, and is lovingly nourished by it.

It may occur to many who watch this documentary that the hummingbirds fortunate enough to fall into Terry’s care receive a parental love and steadfastness unexperienced by many human children. Along those lines, it occurs to Terry late in the documentary that she may have been driven to her work with the hummingbirds because of her terribly abusive childhood. She grew up poor in Wisconsin, and the extent of the abuse she suffered almost killed her. Despite this, she was always a unique set of energies waiting to be channeled into worthy endeavors; when she was in grade school, and the teacher’s prompt to “draw what you want to be when you grow up” produced the predictable firefighter and farmer responses from the boys, and nurses and mothers from the girls, Terry was the odd one out, drawing an androgynous character in a black beret. “Does this mean you want to be an artist?” her teacher asked.

“Sort of…” Terry answered.

Though Terry would probably agree with Walt Whitman when he writes in Song of Myself, “I think I could turn and live with the animals … Not one is dissatisfied, not one is demented with the mania of owning things,” she is no Grizzly Man, nor is she even that radical. She simply uses her resources, which appear quite extensive, to restore to health as many of these magical creatures as possible. Her Xanadu is not a pleasure dome for her, but a heavenly aviary for these fallen fairy feathered wonders.

Terry is not busy about distinctions between hummingbirds and humans; if you close your eyes and hear the authentic care in her voice as she coaxes a bird into steady flight, the power of raising young life into cultivated confidence and safe travels will ensure you aren’t either.

This is a worthy and valuable portrait about one who, like hummingbirds, provide this world with its magical and necessary abnormality. When conformity is uncaring, the eccentricity of Terry’s sympathy becomes a refuge from neglect and blindness.

stills courtesy of Kino Lorber

Every Little Thing

WildBear Entertainment and Dogwoof Releasing

94 Minutes | Australia | in English

opens at the IFC Center in NY January 10

and in LA at the Laemmle Monica in January 17, 2025

with national expansion to follow