ARTHUR MILLER’S CLASSIC DONE TO DEATH

AT THE COLONY THEATRE

What cachet Arthur Miller’s 1949 classic Death of a Salesman has in terms of power and artistry, nuance, subtlety and insight, is buried by Mark Blanchard’s ineffectual staging currently on display at the Colony Theatre. Neither the director nor most of the cast demonstrate anything but the most superficial connection to or emotional understanding of the material in this by-the-numbers interpretation.

This is the story of Willy Loman, a 63-year-old failing salesman whose life and legacy are crushed by the American Dream, making the play as timely now as in 1949. The characters deal with the same economic and social struggles as we do today (there’s even a scene where Willy’s employer is completely distracted by his new recording machine, a foreshadowing of our gadget-filled era). This is why the most heartbreaking moments–if the play is done right–are the happier scenes from Loman’s more optimistic past and the times when a young family and an inspired salesman still had hope that they could live the American Dream.

It is through this juxtaposition of a hopeful past and a hopeless present that we bear witness to the deterioration of Willy’s mental and emotional states–casualties of his failures and regrets, and of a lifetime spent in a futile pursuit of success and approbation, goals which he’s chased without ever asking himself if they were worth pursuing.

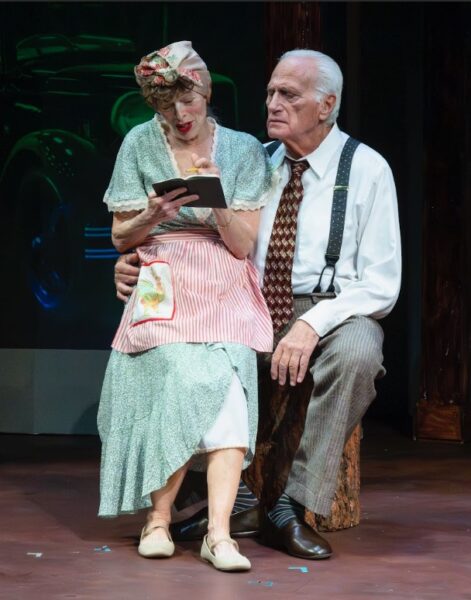

While the real cancer of this revival is the nonexistent direction, the casting is dubious at best. Both Joe Cortese at 76 as Willy and the luminescent Francis Fisher at 72 are simply too old, seeming more like the grandparents of the family. Fisher certainly embodies the love, dedication and patience of Linda. When she claims things will get better, we believe her. But that vivid determination to protect Willy at all costs lays low. As for Mr. Cortese, the energy and personality that should turn on a dime between abject pride, dementia, criticism, and emotional outbursts — a sign of his unmet needs — feel premeditated and clunky. He lacks variation.

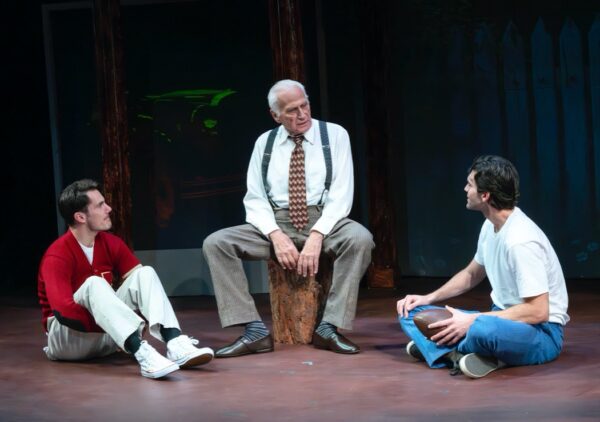

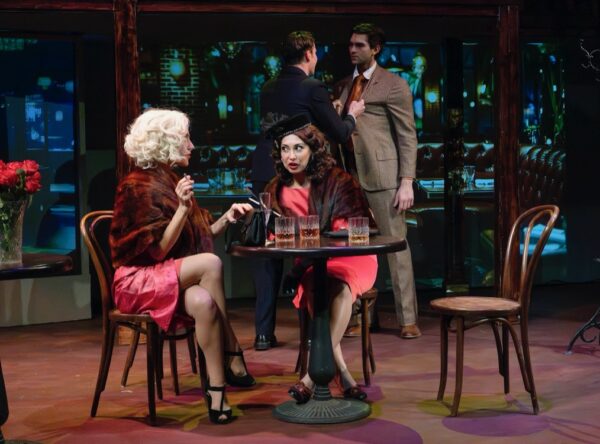

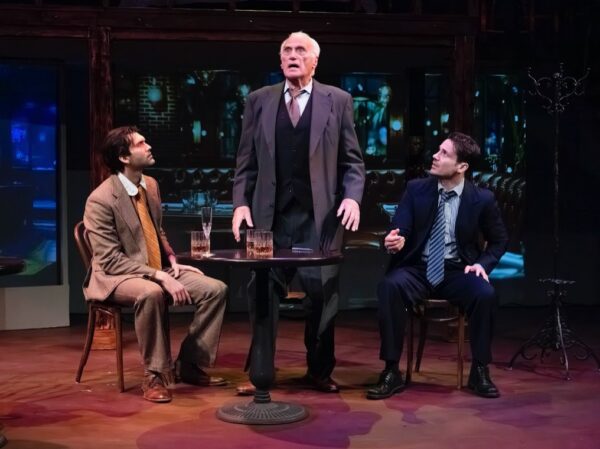

Willie’s only hope now lies with his two boys, who he believes will make something of their lives and in turn save him. But it’s obvious that this will never happen. His sons are as broken as Willie himself. Willy, espousing that the key to a person’s success is being well-liked and attractive, has pushed this dogma on his children. As Biff and Happy, Cronin Cullen and Robert Smythe respectively, are the best in the cast, likeable and definitely attractive; I believe they are brothers, I believe that Biff is a loser who carries the weight of failure on his shoulders, and I believe that Happy is a Casanova who loves sex with women. Still, a modern-day restaurant scene which is supposed to be uncomfortable, even painful, plays out like an acting class, aided by the head-scratching placement of the actors, some of whom are amateurish at best.

But if an actor lacks talent or isn’t right for the part, is that really their fault? In Blanchard’s Salesman, rather than mining their insides for something resembling real feelings, the cast — except for Cullen and Smythe — does a lot of indicating with unemphatic line readings that sound like the performers are afraid of their own voices (far too much of the dialogue was indecipherable). This prevents us from connecting emotionally to the characters, which makes great dialogue fall flat and turns the entire experience into an arduous chore.

The design elements follow Blanchard’s non-vision: The Loman’s furniture is supposed to be faded, but here it looks neglected. That would be fine if furniture choices properly fit other scenes, but here it seems that everyone in 1949 purchased amenities from a garage sale. The lighting by set designer Justin Huen is indistinct with oscillating flood lights from above, and Vicki Conrad‘s costumes were ill-fitting for the most part with too many collars sticking up on the men and a horrifying wig for one actress. Fritz Davis‘s large projections were effective, but did not fully compensate for the relatively unchanging set. And why was the kitchen–the heartbeat of the play–all the way stage left instead of at center? And after the play’s climax, the most off-putting bit of direction arrived with a stagehand running on to clunkily flip over a headstone, the inscription of which faces us, not the characters looking at it.

Blanchard is either deaf to all the false notes or is incapable of correcting them. I lean towards the former, especially considering some of his other directorial choices range from dull to pretentious to ludicrous (during a scene with Willy downstage, Fisher and Smythe sit at the top of the stairs looking like lovers cooing and embracing). Additionally at last night’s opening, the cast did not actively listen to each other, fumbling some lines and stepping on others. I wondered if this was due to the postponement of last Saturday’s original opening date because of the Los Angeles fires, but this meant they had even more preview performances to get it right. And we are told that the runtime is 120 minutes with intermission, but including a late start, we were there nearly 3 and 1/2 hours. Ugh. Murdered by Death.

photos by Billy W. Bennight II

Death of a Salesman

Panic! Productions

Colony Theater, 555 N Third St. in Burbank

free parking in the multi-level lot adjacent to the theater

Tues-Sat at 7:30; Sun at 3:30; Sat at 3:30 (Jan 25)

ends on January 26, 2025

for tickets ($35-$65), visit OnStage411

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

While a few of the actors manage to very occasionally eek out a believable and effective line reading this 3 hour snooze-fest is misguided from the very first line to the last. I am a big Frances Fisher fan but she delivers one of the worst stage performances I’ve seen in years. I know she is more than capable so I can only blame the director who offers absolutely zero help to any of the actors. The Best Play Ever Written?!?!?! You’d never know it from this production!