SWEET BEGINNINGS

It is thrilling to hear the poetic dialogue of a propitious new American playwright for the first time; one who uses a unique, innovative and visionary arrangement of words that not only awaken your senses, but heighten your hopes that the profligate use of technological blather will not drown out a voice which is at once rich, challenging and distinctive.

That playwright is Tarell Alvin McCraney, and the play witnessed is Marcus; Or The Secret Of Sweet at the American Conservatory Theater. McCraney, just three years out of Yale, has had his plays produced in (amongst other cities) New York, Chicago, Seattle, and London (where he is only the third dramatist to become the International Playwright in Residence at the Royal Shakespeare Company). Marcus is the final installment of McCraney’s triptych, The Brother/Sister Plays which includes In the Red and Brown Water and The Brothers Size, both having recently been produced, respectively, at Marin Theatre Company and Magic Theatre.

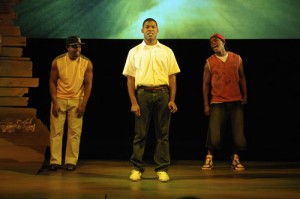

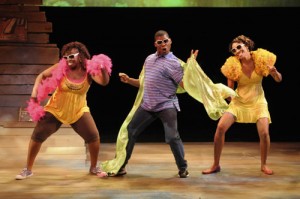

A.C.T. consistently mounts handsome productions, and Marcus is no exception. Associate artistic director Mark Rucker did the best he could with a piece that is far better suited to an intimate house; indeed, the simplicity of his staging actually heightens the impact of McCraney’s dialogue, and Alexander V. Nichols’ stunning projection design creates as many moods as the weather it conveys. All of the acting is superlative (two of the cast are members of A.C.T.’s MFA Program class of 2011), but the crux of this review is about Tarell Alvin McCraney: you will be hearing from this playwright in the future, and it’s time to prick up your ears.

Marcus is a gay coming-of-age play. It seems that all of the inhabitants we meet in hurricane-prone San Pere, Louisiana, either know or suspect that 16-year-old Marcus (Richard Prioleau) is “sweet” – i.e., gay. Marcus certainly supposes he is, but he has yet to make a self-declaration. He even asks his mother, Oba (Margo Hall) if his deceased father was “sweet.” Oba refuses to discuss it, but tells Marcus that he best pray if such “sleeping traits awake in him.” Marcus’ friend, Shaunta (Omozé Idehenre) tries to elicit an admission of “sweetness” from Marcus by asking him to consider what it must have been like for slaves. It is a moment worthy of elucidating the power of McCraney’s words:

Round here Niggas think they got it Hard on the ’˜down low’’¦

What about back then?

Two slaves one dark, and one light, one house

And the other field. They see each other one day.

That sparkle in they eye, they begin to gather

Together when they can, hide their love from the light.

The playwright assumes no hidden messages – it is a day-in-the-life of a poor, rural community in the Deep South – but the themes are universal. We are introduced to people who are mystics and two-timers; people who are jealous and unforgiving; people who alienate and abandon. Not for once do we judge these people – they are doing the best they can with what they have been handed, including the threat of a massive storm that Marcus sees in his tormenting dreams. (Of course Marcus is haunted by dreams and shame – he is yearning for liberation; as with Hamlet, the use of soliloquies offers insight into the torment of our struggling protagonist.)

One of the most fascinating elements is that the characters speak many of their stage directions: “Marcus exits,” or “She smacks her teeth.” It tells us that affectations (the way a hand is waved, for example) are an integral component of their language. It also serves to draw in the audience and create a connection with the characters – a connection so profound that it was startling to discover that San Pere is a fictional community, born of the imagination of a writer who is simply creating an amalgam of the cultures he has known, very much like (dare I say it?) Tennessee Williams.

Those audience members who are not used to active listening may find parts of Marcus downright inaccessible. The characters – Oshoosi, Elegua, Oshun – are named after Yoruba deities (Yoruba is a large ethnic group in western Africa), and you may scratch your head a few times trying to remember who is who. Also, the idiomatic language may be alienating to those unfamiliar with urban slang: when smooth-talking Shua (Tobie L. Windham) announces his entrance with: “Enter Shua with his Kangol/Low’¦Down Low,” I wondered how many folks know that Kangol is a hat, and that “Down Low” refers to seemingly straight black men who have sex with other men on the sly. Of course, we can figure that out in the ensuing scene, but some folks may feel like they’re playing catch-up; in fact, Act II may have already begun before you find yourself acclimated to this new voice. (I myself have yet to read or see McCraney’s other works.)

It is clear now why the run is so short: regardless of my praise (I’m a sucker for an innovative wordsmith), Marcus itself is still a work-in-progress. Auspicious playwrights in America deserve fully mounted productions such as this; we can rest assured that McCraney has been discovered, and is being nurtured by some of the most amazing directors and theatre companies in the world, Mr. Rucker and A.C.T. included. Theatre, like Marcus itself, is about community.

photos by Kevin Berne

Marcus; Or The Secret Of Sweet

American Conservatory Theater

A.C.T.’s Geary Theater, 415 Geary Street

scheduled to end on November 21, 2010

for tickets, call 415.749.2228 or visit ACT SF