THE NEW TRADITION OF AWARD-WINNING

MUSICAL WORKS-IN-PROGRESS

In the evolutionary process of the modern Broadway musical, Next to Normal is still somewhere between ape and man; for all the pioneering and innovative writing, intriguing subject matter, and outstanding performances, the finished product left me frustrated that it didn’t live up to its own potential. There are many ingredients that validate the shows popularity: it is to be commended for a bold and daring new way of communicating the kind of subject matter that you would expect from Albee or O’Neill rather than musical theater. The story of a family dealing with the seemingly irresolvable dilemma regarding mental illness is told with compassion and honesty in a most compelling manner. Librettist Brian Yorkey has written tremendously honest dialogue, and there are surprising twists and turns as medical treatment becomes more perplexing than the disease itself. A play about mental illness is daring enough, but to musicalize it and even be partially successful is amazing. But something is amiss and I truly believe that Next to Normal is still an unfinished product, regardless of the maelstrom of hype that is bestowed on this Tony and Pulitzer Prize winner.

In the evolutionary process of the modern Broadway musical, Next to Normal is still somewhere between ape and man; for all the pioneering and innovative writing, intriguing subject matter, and outstanding performances, the finished product left me frustrated that it didn’t live up to its own potential. There are many ingredients that validate the shows popularity: it is to be commended for a bold and daring new way of communicating the kind of subject matter that you would expect from Albee or O’Neill rather than musical theater. The story of a family dealing with the seemingly irresolvable dilemma regarding mental illness is told with compassion and honesty in a most compelling manner. Librettist Brian Yorkey has written tremendously honest dialogue, and there are surprising twists and turns as medical treatment becomes more perplexing than the disease itself. A play about mental illness is daring enough, but to musicalize it and even be partially successful is amazing. But something is amiss and I truly believe that Next to Normal is still an unfinished product, regardless of the maelstrom of hype that is bestowed on this Tony and Pulitzer Prize winner.

Interestingly enough, as with director Michael Greif’s earlier Broadway hit, Rent (which cemented the trend of social stigma as the theme of a Broadway musical), Next to Normal also feels like an incomplete show that was catapulted into legendary status by Tony Awards and a Pulitzer Prize. (The death of composer Jonathon Larson on the eve of Rent’s Off-Broadway premiere also sealed its status as a critique-proof phenomenon.)

I want to rave about Next to Normal simply based on its originality, but feel compelled to point out gaps and inconsistencies because, as original as the creators are, the show circumnavigated my heart; the journey never made it inside.

I want to rave about Next to Normal simply based on its originality, but feel compelled to point out gaps and inconsistencies because, as original as the creators are, the show circumnavigated my heart; the journey never made it inside.

I want to rave about Tony-winner Alice Ripley’s raw and strong portrayal of Diana, the mother lost in a sea of medication used to treat a bipolar depressive disorder, but her Melissa Etheridge /Betty Buckley vocals were, at times, unintelligible and garbled, made even more thrashing due to the rock concert volume necessary to fill the ghastly aural vacuum at the Ahmanson Theatre, which, as usual, sucks up smaller plays and musicals that would fare much better in an intimate house, such as the 766-seat Booth Theatre in New York, where the Broadway production still resides. The kick-off of the National Tour here in Los Angeles proves that some shows suffer when a tour plays a 1,600-seat house; the sheer size disconnects us from our relationship to the show, as it did with Spring Awakening and Doubt, just a few of the shows ill-suited to the Ahmanson.

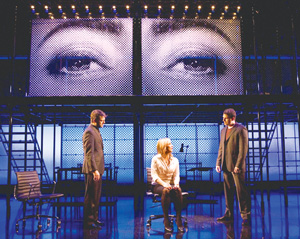

I want to applaud Michael Greif’s inventive direction, one that is able to fill the entire proscenium on Mark Wendland’s tri-level set, but I can’t help but shake the feeling that this set could be used for any Rock and Roll show (and in fact a similar set was used for Jersey Boys).

I want to applaud Michael Greif’s inventive direction, one that is able to fill the entire proscenium on Mark Wendland’s tri-level set, but I can’t help but shake the feeling that this set could be used for any Rock and Roll show (and in fact a similar set was used for Jersey Boys).

I love Tom Kitt’s fusion of modernistic rock and old-time Broadway inventiveness (Mozart is used as a background for one character’s lament, just as Beethoven was used as underscoring for Lucy in You’re A Good Man, Charlie Brown), but even while admiring Kitt’s wholly original sound, I found myself yearning for that one ballad, that one tuneful eleven o’clock number, but it never came; even Burt Bacharach’s 1968 wacky score of Promises, Promises was made all the more palatable with the accessible ballad, “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again.”

I want to notice that I had an emotional pit in my stomach because the creators took me on a harrowing journey of a family’s tragic ordeal — one which vividly brings to mind my own family dynamics; at the same time, I wondered why we were brought to the edge of catharsis time and again with no resolution. Lucky is the audience member who could wipe away a tear at the end, but some may feel emotionally constipated — especially considering that obtrusive ending that seemed to say, “We aren’t going to end this show on an upbeat note, but if we suddenly make the music buoyant, and shine mega-watts of bright light in your faces while the rear of the stage is awash in sky-blue, you will leave the theater fulfilled.”

I want to say, “How brave to have a musical mirror life and not wrap up the yarn of predicament in a neat, little bow at the end.” But instead of inspiring me to discuss my own personal journey involving a family member’s mental illness (and the frustrating feeling that somehow, somewhere there must be a drug that will induce a degree of normalcy), I am haunted, plagued and mystified by a cornucopia of questions regarding plot and construction of the show.

What you need to take after seeing Next to Normal depends on your tastes. I dare say that I didn’t hate the show, but as with Diana’s pharmacological conundrum, you will either reach for a Kleenex, a Xanax, an aspirin, or Milk of Magnesia to soothe whatever it is that ails you.

photos by Craig Schwartz

Next to Normal

ends on January 2, 2010 at the Ahmanson

tour continues through July 31, 2010

for cities, dates, and tickets, visit Next to Normal

ready

Next to Normal

NEXT TO NORMAL book and lyrics by Brian Yorkey, music by Tom Kitt – with Alice Ripley – Los Angeles leg of the Touring Production – Musical Theater Review

THE NEW TRADITION OF AWARD-WINNING MUSICAL WORKS-IN-PROGRESS

In the evolutionary process of the modern Broadway musical, NEXT TO NORMAL is still somewhere between ape and man; for all the pioneering and innovative writing, intriguing subject matter and outstanding performances, the finished product leaves us frustrated that it doesn’t live up to its own potential. There are many ingredients that validate the shows popularity: it is to be commended for a bold and daring new way of communicating the kind of subject matter that you would expect from an Albee or O’Neill rather than musical theatre. The story of a family dealing with the seemingly irresolvable dilemma regarding mental illness is told with compassion and honesty in a most compelling manner. Librettist Brian Yorkey has written tremendously honest dialogue, and there are surprising twists and turns as medical treatment becomes more perplexing than the disease itself. A play about mental illness is daring enough, but to musicalize it and even be partially successful is amazing. But something is amiss and I truly believe that NEXT TO NORMAL is still an unfinished product, regardless of the maelstrom of hype that is bestowed on this Tony and Pulitzer Prize winner.

Interestingly enough, like director Michael Greif’s earlier Broadway hit, RENT (which cemented the trend of social stigma as the theme of a Broadway musical), NEXT TO NORMAL also feels like an incomplete show that was catapulted into legend status by Tony Awards and a Pulitzer Prize. (The death of composer Jonathon Larson on the eve of RENT’s Off-Broadway premiere also sealed its status as a critique-proof phenomenon).

You want to rave about NEXT TO NORMAL simply based on its originality, but you feel compelled to point out gaps and inconsistencies because, as original as the creators are, the show circumnavigated your heart; the journey never made it inside.

You want to rave about Tony-winner Alice Ripley’s raw and strong portrayal of Diana, the mother lost in a sea of medication used to treat a bi-polar disorder, but you feel the need to comment that her Melissa Etheridge/Betty Buckley vocals are, at times, unintelligible and garbled, made even more thrashing due to the rock concert volume necessary to fill the ghastly vacuum at the Ahmanson theatre (which, as usual, sucks up smaller plays and musicals that would fare much better in an intimate house). The raves from trustworthy friends who have seen the show at the intimate, 766-seat Booth Theatre in New York validate my conclusion that some shows suffer when a touring company plays a 1,600-seat house; the sheer size disconnects us from our relationship to the show (as it did with SPRING AWAKENING and DOUBT, to name a couple of shows that suffered that fate at the Ahmanson).

You want to applaud Michael Greif’s inventive direction, one that is able to fill the entire proscenium on Mark Wendland’s tri-level set, but you can’t help but shake the feeling that this set could be used for any Rock and Roll show (and in fact a similar set was used for JERSEY BOYS).

You love Tom Kitt’s fusion of modernistic rock and old-time Broadway inventiveness (Mozart is used as a background for one character’s lament, just as Beethoven was used as underscoring for Lucy in YOU’RE A GOOD MAN, CHARLIE BROWN), but even while admiring Kitt’s wholly original sound, you find yourself yearning for that one ballad, that one tuneful eleven o’clock number, but it never came; even Burt Bacharach’s 1968 wacky score of PROMISES, PROMISES was made all the more palatable with the accessible ballad, “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again.”

You want to notice that you have an emotional pit in your stomach because the creators take you on a harrowing journey of a family’s tragic ordeal – one which vividly brings to mind your own family dynamics; at the same time, you wonder why we are brought to the edge of catharsis time and again with no resolution. Lucky is the audience member who can wipe away a tear at the end, but some may feel emotionally constipated – especially considering that obtrusive ending that seems to say, “We aren’t going to end this show on an upbeat note, but if we suddenly make the music buoyant, and shine mega-watts of bright light in your faces while the rear of the stage is awash in sky-blue, you will leave the theatre fulfilled.”

You say to yourself, “How brave to have a musical mirror life and not wrap up the yarn of predicament in a neat, little bow at the end!” But instead of inspiring me to discuss my own personal journey involving a family member’s mental illness (and the frustrating feeling that somehow, somewhere there must be a drug that will induce a degree of normalcy), I am haunted, plagued and mystified by a cornucopia of questions regarding plot and construction of the show.

What you need to take after seeing NEXT TO NORMAL depends on your tastes. I dare say that I didn’t hate the show, but as with Diana’s pharmacological conundrum, you will either reach for a Kleenex, a Xanax, an aspirin, or Milk of Magnesia to soothe whatever it is that ails you.

tonyfrankel @ stageandcinema.com

photos by Craig Schwartz

scheduled to close January 2 at time of publication

for tickets, visit http://www.centertheatregroup.org/

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

As usual, Mr. Frankel, you choose snarkiness and the shallow surface interpretation over actually giving a show a chance. Not surprising, given most of your reviews but it grows tiresome after awhile. You may think you’re John Simon, but you have a long way to go and a lot better writing to aspire to if you want to even get near that type of reviewing.