STAGNANT YET SATIATING

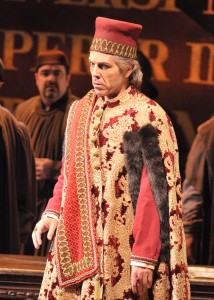

Giuseppe Verdi wrote Simon Boccanegra in 1857, but it is the revised 1881 version which the Lyric Opera is presenting in a stiff yet satisfying production. After searching for his lost daughter (reappearing later as Amelia), Simon Boccanegra (Thomas Hampson) returns to Genoa to find the corpse of his lover and her vengeful father, Fiesco, played by a heart-breaking Ferruccio Furlanetto, a veteran of this role whose voice reaches heavenly foghorn range in his aria, “Il  Lacerato Spirito.” Boccanegra becomes doge in Genoa at the urging of his power-hungry and conniving friend Poalo (a sly Quinn Kelsey); despite his character’s treachery, Kelsey is always welcome on stage because of the thrilling uneasiness he conjures.

Lacerato Spirito.” Boccanegra becomes doge in Genoa at the urging of his power-hungry and conniving friend Poalo (a sly Quinn Kelsey); despite his character’s treachery, Kelsey is always welcome on stage because of the thrilling uneasiness he conjures.

The rest of the opera takes place twenty-five years later when Boccanegra has overcome his tragic youth, becoming a resolute leader who is guided by duty and hardened by lost love. Through an authoritative, yet pained voice, Thomas Hampson skillfully projects Boccanegra’s balance of power and vulnerability, the latter most profound during a touching duet when Boccanegra finally finds his daughter, Amelia (Krassimira Stoyanova), and his tough exterior falls. As Amelia, Stoyanova’s voice effortlessly floats from her chest, a fresh soprano spark in Verdi’s murk of deep basses and baritones. As she sings with her suitor, Adorno (Frank Lopardo), the love of the young couple is palpable.

Director Elijah Moshinsky has lightened this heavy tragedy of betrayal with some well-placed comic timing and acting that avoids melodrama. It’s a nuanced interpretation, suffusing the unlikely, coincidence-crammed plot with realism. Unfortunately, Moshinksy focused his efforts solely on his players’ minute gestures—facial expressions, postures—ignoring their grander movements. When not singing, cast members remain remarkably still on stage, as if they’re just waiting their turns. And when singing, performers stand like petrified wood as if they fear losing their voices. And the few times that the giant chorus appears, the members act as if they were just part of the set rather than characters.

Director Elijah Moshinsky has lightened this heavy tragedy of betrayal with some well-placed comic timing and acting that avoids melodrama. It’s a nuanced interpretation, suffusing the unlikely, coincidence-crammed plot with realism. Unfortunately, Moshinksy focused his efforts solely on his players’ minute gestures—facial expressions, postures—ignoring their grander movements. When not singing, cast members remain remarkably still on stage, as if they’re just waiting their turns. And when singing, performers stand like petrified wood as if they fear losing their voices. And the few times that the giant chorus appears, the members act as if they were just part of the set rather than characters.

Michael Yeargan’s grand but sleek and simple set designs succeed in transporting us to fourteenth-century Genoa, yet he eschews the ostentatiousness associated with the court of Piazza San Marco: The thirty-foot tall pillars speak for themselves, but  very, very quietly. Similarly, Peter J. Hall’s costumes are accurate, yet understated: The chorus members’ washed-out colors don’t overwhelm the eye, even as dozens of them fill the stage, and Amelia’s plain dresses, while highlighting her virtue, let Stoyanova’s voice provide the only ornamentation to the scenes. Still, the visual sparseness disappoints a little; with a score that is mostly forgettable, Moshinsky’s static staging and simplistic visuals are hardly what the Lyric Opera needs to attract non-opera folk.

very, very quietly. Similarly, Peter J. Hall’s costumes are accurate, yet understated: The chorus members’ washed-out colors don’t overwhelm the eye, even as dozens of them fill the stage, and Amelia’s plain dresses, while highlighting her virtue, let Stoyanova’s voice provide the only ornamentation to the scenes. Still, the visual sparseness disappoints a little; with a score that is mostly forgettable, Moshinsky’s static staging and simplistic visuals are hardly what the Lyric Opera needs to attract non-opera folk.

Nonetheless, the music makes a strong impact in the moment. Sir Andrew Davis masterfully conducts Verdi’s score as it roams through a throng of human emotion; there’s a momentum to the music and the story that will carry patrons smoothly through the prologue and three acts.

Despite Simon Boccanegra’s lack of memorable arias, Verdi has wrought a poignant opera brimming with humanity. Behind their facades as politician, betrayer, rebel, and avenger, the men in Simon Boccanegra are, at the core, lovers—of country and of a beautiful young woman named Amelia. The rich and complex story transcends the genre of tragedy, and leaves us with a thought-provoking, universal question: With his affairs in order—and peace in his family and country—is it really sad for a man to die if he has accomplished what he wanted from life? There’s a bittersweet sense of regret, but there’s also an unarguable inevitability that leaves us (perhaps stubbornly) content.

Despite Simon Boccanegra’s lack of memorable arias, Verdi has wrought a poignant opera brimming with humanity. Behind their facades as politician, betrayer, rebel, and avenger, the men in Simon Boccanegra are, at the core, lovers—of country and of a beautiful young woman named Amelia. The rich and complex story transcends the genre of tragedy, and leaves us with a thought-provoking, universal question: With his affairs in order—and peace in his family and country—is it really sad for a man to die if he has accomplished what he wanted from life? There’s a bittersweet sense of regret, but there’s also an unarguable inevitability that leaves us (perhaps stubbornly) content.

photos by Dan Rest

Simon Boccanegra

Lyric Opera in Chicago

scheduled to end on November 9 2012

for tickets, go to Lyric Opera

for info on this and other Chicago Theater, visit http://www.TheatreinChicago.com