SALVATION IN A STORM

Who is the titular Flying Dutchman? Is he a mythological figure, a type of the wandering Jew bound to traverse the earth in travail until his day of salvation comes? Is he in some way the composer, an outsider and a genius yearning for acceptance and recognition? Or he is simply a lonely man looking for love? The genius of Richard Wagner’s The Flying Dutchman is that it can be read on so many levels. Of course, Wagner didn’t create the story, which is largely based on Heinrich Heine, but he did write his own libretto and music.

The Flying Dutchman marks a “quantum leap” in Wagner’s oeuvre, as James Conlon argued in his pre-opera talk at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. Although the composer had written three operas previously, they are now considered juvenilia in contrast to the mature voice that emerges in The Flying Dutchman. Also Wagner’s shortest opera, it runs just two hours and twenty minutes without intermission. And that is exactly how LA Opera’s latest production unfolds. Storm follows storm in a terrific tour-de-force from the opening overture to the fatal finale. While the storms provide a unifying force in the drama, the production itself is somewhat disjointed. First, there is Wagner’s realistic scoring, which deftly mimics the howling winds and crashing waves of a storm at sea. Yet, there is nothing terribly stormy about what happens on stage. A wave-patterned curtain provides some visual cue and there are smoke effects that add to the mystery, but Nikolaus Lehnhoff’s production does little to heighten the drama.

The Flying Dutchman marks a “quantum leap” in Wagner’s oeuvre, as James Conlon argued in his pre-opera talk at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. Although the composer had written three operas previously, they are now considered juvenilia in contrast to the mature voice that emerges in The Flying Dutchman. Also Wagner’s shortest opera, it runs just two hours and twenty minutes without intermission. And that is exactly how LA Opera’s latest production unfolds. Storm follows storm in a terrific tour-de-force from the opening overture to the fatal finale. While the storms provide a unifying force in the drama, the production itself is somewhat disjointed. First, there is Wagner’s realistic scoring, which deftly mimics the howling winds and crashing waves of a storm at sea. Yet, there is nothing terribly stormy about what happens on stage. A wave-patterned curtain provides some visual cue and there are smoke effects that add to the mystery, but Nikolaus Lehnhoff’s production does little to heighten the drama.

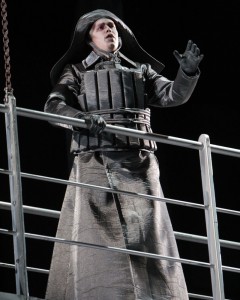

Wagner’s realistic scoring, moreover, is not mirrored in Andrea Schmidt-Futterer’s costume design. There is nothing remotely sailor-like in the sailors’ appearance or captain-like in that of Daland or the Dutchman. Daland especially is a campy caricature, who boasts a monstrous wig and makeup. The Dutchman oddly appears more clerical than ghostly, apart from his white face paint. He wears what looks like a priest’s black cassock (sans white collar), caped cloak and wide-brimmed hat. Daland’s shiny, brightly-colored garb is almost episcopal with his big hair standing duty for a bishop’s mitre. Yet, these two characters are those most in need of salvation. Only Erik and Senta wear conventional attire.

Wagner’s realistic scoring, moreover, is not mirrored in Andrea Schmidt-Futterer’s costume design. There is nothing remotely sailor-like in the sailors’ appearance or captain-like in that of Daland or the Dutchman. Daland especially is a campy caricature, who boasts a monstrous wig and makeup. The Dutchman oddly appears more clerical than ghostly, apart from his white face paint. He wears what looks like a priest’s black cassock (sans white collar), caped cloak and wide-brimmed hat. Daland’s shiny, brightly-colored garb is almost episcopal with his big hair standing duty for a bishop’s mitre. Yet, these two characters are those most in need of salvation. Only Erik and Senta wear conventional attire.

Then there is Wagner’s mythology, which is curiously reflected in the male and female choruses. Every member of each of these choruses looks exactly identical. There is nothing individual or distinguishing, since all wear the same costumes, wigs and makeup. And those costumes give their wearers the look of machines: monochrome in color with lots of round, bulbous shapes. In such clothing they cannot move gracefully, which makes what little dance choreography there is appear awkward and stilted. All of this gives the production an almost abstract and impersonal feel, which is decidedly at odds with the romanticism of Wagner’s story and score.

Then there is Wagner’s mythology, which is curiously reflected in the male and female choruses. Every member of each of these choruses looks exactly identical. There is nothing individual or distinguishing, since all wear the same costumes, wigs and makeup. And those costumes give their wearers the look of machines: monochrome in color with lots of round, bulbous shapes. In such clothing they cannot move gracefully, which makes what little dance choreography there is appear awkward and stilted. All of this gives the production an almost abstract and impersonal feel, which is decidedly at odds with the romanticism of Wagner’s story and score.

While Raimund Bauer’s set design is similarly abstract and static, it does provide a novel way of portraying Senta’s predestined love affair with the Dutchman. Whereas many other productions literally use a painted portrait as a prop that Senta can embrace, Bauer opts for a screen stamped with the imprint of the Dutchman’s shadow. This highly-effective rendering gives the Dutchman a larger-than-life presence in the story and allows the cast to face the audience beyond the screen. Unfortunately, this means that for most of the opera’s duration either the screen of the Dutchman or of the storm acts as a barrier between the cast and the audience.

While Raimund Bauer’s set design is similarly abstract and static, it does provide a novel way of portraying Senta’s predestined love affair with the Dutchman. Whereas many other productions literally use a painted portrait as a prop that Senta can embrace, Bauer opts for a screen stamped with the imprint of the Dutchman’s shadow. This highly-effective rendering gives the Dutchman a larger-than-life presence in the story and allows the cast to face the audience beyond the screen. Unfortunately, this means that for most of the opera’s duration either the screen of the Dutchman or of the storm acts as a barrier between the cast and the audience.

Under James Conlon’s superior conducting, The Flying Dutchman soars even despite Lehnhoff’s disjointed production and a last minute cast change: Just seconds before the overture began on opening night, Christopher Koelsch, President and CEO of LA Opera, announced that soprano Elisabete Matos had suddenly become indisposed. Los Angeles-native Julie Makerov quickly stepped in to play Senta, Daland’s daughter (Makerov previously sang the role to great acclaim with the Canadian Opera Company in 2010). Her performance was surprisingly good considering the circumstances. Indeed, Makerov acquitted herself with incredible poise, imbuing the descending tones of Senta’s aria “Traft ihr das Schiff” with characteristic passion, and the finale with tragic determination. While she remained relatively stationary onstage, that was perhaps more a reflection of Wagner’s introspective narrative and Lehnhoff’s abstract production than any hesitancy or lack of readiness on her part.

Under James Conlon’s superior conducting, The Flying Dutchman soars even despite Lehnhoff’s disjointed production and a last minute cast change: Just seconds before the overture began on opening night, Christopher Koelsch, President and CEO of LA Opera, announced that soprano Elisabete Matos had suddenly become indisposed. Los Angeles-native Julie Makerov quickly stepped in to play Senta, Daland’s daughter (Makerov previously sang the role to great acclaim with the Canadian Opera Company in 2010). Her performance was surprisingly good considering the circumstances. Indeed, Makerov acquitted herself with incredible poise, imbuing the descending tones of Senta’s aria “Traft ihr das Schiff” with characteristic passion, and the finale with tragic determination. While she remained relatively stationary onstage, that was perhaps more a reflection of Wagner’s introspective narrative and Lehnhoff’s abstract production than any hesitancy or lack of readiness on her part.

There is not a single weak voice in LA Opera’s stellar cast. Bass-baritone Tomas Tomasson, a native of Iceland, plays the part of the Dutchman with fitting anguish and mystery. While Tomasson sings beautifully, it’s not easy to like and sympathize with his brooding character. Bass James Creswell as Daland, tenor Matthew Plenk as the Steersman, mezzo-soprano Ronnita Nicole Miller as Mary and tenor Corey Bix as Erik contribute some welcome humor to a mostly serious story. Bix and Creswell in particular add a more human element to the mythological romance at the center of The Flying Dutchman. Bix is perfectly buffoonish as the suitor whose love of Senta is unrequited. And Creswell plays Daland – who basically sells his daughter in marriage – as grotesquely grasping and greedy, though his warm bass endows the character with some warmth.

There is not a single weak voice in LA Opera’s stellar cast. Bass-baritone Tomas Tomasson, a native of Iceland, plays the part of the Dutchman with fitting anguish and mystery. While Tomasson sings beautifully, it’s not easy to like and sympathize with his brooding character. Bass James Creswell as Daland, tenor Matthew Plenk as the Steersman, mezzo-soprano Ronnita Nicole Miller as Mary and tenor Corey Bix as Erik contribute some welcome humor to a mostly serious story. Bix and Creswell in particular add a more human element to the mythological romance at the center of The Flying Dutchman. Bix is perfectly buffoonish as the suitor whose love of Senta is unrequited. And Creswell plays Daland – who basically sells his daughter in marriage – as grotesquely grasping and greedy, though his warm bass endows the character with some warmth.

The titular Flying Dutchman ultimately finds his salvation in the midst of the storm. She is Senta, a woman who rescues him from an eternity on the seas. In her, Wagner created a kind of character that would reappear often in his works, that of the redemptive woman. And in the Dutchman, Wagner created his archetypal outsider. Both characters live on in the majestic musical motives that he wrote for each, melodies that are not easily forgotten. If The Flying Dutchman is a triumph of Wagner’s art, LA Opera’s production is a bit like the composer’s own mixed reputation: a combination of genius and flawed vision.

The titular Flying Dutchman ultimately finds his salvation in the midst of the storm. She is Senta, a woman who rescues him from an eternity on the seas. In her, Wagner created a kind of character that would reappear often in his works, that of the redemptive woman. And in the Dutchman, Wagner created his archetypal outsider. Both characters live on in the majestic musical motives that he wrote for each, melodies that are not easily forgotten. If The Flying Dutchman is a triumph of Wagner’s art, LA Opera’s production is a bit like the composer’s own mixed reputation: a combination of genius and flawed vision.

photos by Robert Millard

The Flying Dutchman

LA Opera at Dorothy Chandler Pavilion

scheduled to end on March 30, 2013

for tickets, call (213) 972-8001 or visit LA Opera