A FISH OUT OF WATER

Ten years ago, the Tim Burton film Big Fish with Ewan McGregor and Albert Finney, based on Daniel Wallace’s 1998 “novel of mythic proportions,” charmed audiences with its depiction of tall tales turned true. A tribute to storytelling as a gift from one generation to the next, Big Fish is a perfect case of American magical realism. Its downhome Alabama saga is a triumph of imagination which leads to one of the most perfect deaths – and deathbed reconciliations – ever depicted on any screen.

The movie was sweetly uninsistent even as it celebrated exaggeration as an art form. Whether it needs to be turned into a musical is the latest case of apples becoming oranges. Finally opening at the Oriental Theatre as a pre-Broadway tryout, it’s no work-in-regress, but it badly needs fine tuning – emotionally, that is. The show is all too efficient, as you’d expect from director Susan Strohman, a show-woman in the Tamor tradition who can animate a cemetery, but she sometimes fails to find the emotionally intended heart of her source material.

That novel spins the stories invented by Edward Bloom (Broadway veteran Norbert Leo Butz), a traveling salesman in the deep South who combines Baron Munchausen, Paul Bunyan, and Walter Mitty in his fervent attempts to improve on truth. At least that’s how his literal-minded son Will (affable Bobby Steggert), a New York Times reporter who prefers facts over fiction, sees his now-dying dad. But, steadfast throughout, Will’s mother Sandra (elegant Kate Baldwin) is a wife who loves Edward for all his flaws, not despite them.

Now married to the Parisian sophisticate Josephine (Krystal Joy Brown), Edward slowly stumbles onto discoveries about his dad that make his father’s tale-spinning seem less an embarrassment than a destiny. At that point, Will starts to wonder: What if his expected son one day dismisses him too as a liar, or, if not, will he wish that dad had enriched a reality that required embellishment?

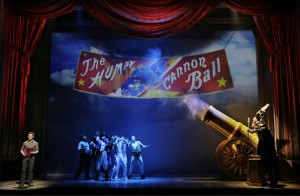

These adventures are depicted with a supple video backdrop and ingenious rolling and flying props by Julian Crouch. They’re equally energized, if not overinterpreted, by Andrew Lippa’s so-so songs, where subtext is never sub. Edward’s adventures begin on the day when Will was born, when Edward set off on an odyssey involved a giant catfish and the gold ring that was used in a futile attempt to catch him. One good whopper deserves another: We’re regaled with depictions of Edward’s swamp-ridden encounter with a Witch (Katie Thompson) who tells him how he’ll die; a mermaid; and a giant who becomes a celebrity. There is also his sojourn with a circus run by avuncular Amos Calloway (Brad Oscar); his passion for daffodil-loving Sandra at Auburn College, and, in the second act, his heroic rescue of the hamlet of Ashton from a flood (a change from the film’s foreclosures) and his abortive love affair with high school sweetheart Jenny Hill (Kirsten Scott).

These adventures are depicted with a supple video backdrop and ingenious rolling and flying props by Julian Crouch. They’re equally energized, if not overinterpreted, by Andrew Lippa’s so-so songs, where subtext is never sub. Edward’s adventures begin on the day when Will was born, when Edward set off on an odyssey involved a giant catfish and the gold ring that was used in a futile attempt to catch him. One good whopper deserves another: We’re regaled with depictions of Edward’s swamp-ridden encounter with a Witch (Katie Thompson) who tells him how he’ll die; a mermaid; and a giant who becomes a celebrity. There is also his sojourn with a circus run by avuncular Amos Calloway (Brad Oscar); his passion for daffodil-loving Sandra at Auburn College, and, in the second act, his heroic rescue of the hamlet of Ashton from a flood (a change from the film’s foreclosures) and his abortive love affair with high school sweetheart Jenny Hill (Kirsten Scott).

Ironically, Strohman’s choreography leaves little to the imagination: It turns the Witch’s “I Know What You Want” into a swirling masque of transient trees; the first-act finale into a stage-wide burst of blossoms; and the circus into a one-ring romp complete with “cobblestone cloggers” and the bouncing rear ends of three plucky pachyderms. Some of these images are as beautiful to behold as those in the film.

Unfortunately, book and screenwriter John August goes wrong in the second act when he fatefully underpresents the toy town of Ashton and neglects how Edward both transforms it and lets it fail. Even worse are irrelevant musical numbers with  no roots in the film, though they may appear in Wallace’s novel: “Red, White, and True,” an elaborate production number that begins as a campfire confession and explodes into an overproduced USO spectacle and, even more absurd, “Showdown,” a Wild West homage that too literally fleshes out the temperamental conflicts between Edward and Will. Even given this story, less can be more.

no roots in the film, though they may appear in Wallace’s novel: “Red, White, and True,” an elaborate production number that begins as a campfire confession and explodes into an overproduced USO spectacle and, even more absurd, “Showdown,” a Wild West homage that too literally fleshes out the temperamental conflicts between Edward and Will. Even given this story, less can be more.

It’s the quieter moments that ring true enough to recall the film, like Edward and Sandra’s lovely ballad “Daffodils” and the duet “Fight the Dragons” between father and son that begins the healing well before Edward dies. Unlike the movie, Edward’s apotheosis as he returns to the river, surrounded by the characters he created (or did he?), seems rushed, less than the powerful sendoff that could bring Big Fish full circle. There were few wet eyes in the house.

At its best, the musical ratifies the film’s credo’”that art is the lie that tells the truth. As is, however, it mistakes the package for the present, over-illustrating a plot that needs a heart.

photos by Paul Kolnik

Big Fish

Oriental Theatre

scheduled to end on May 5, 2013

for tickets, visit (800) 775-2000 or visit http://www.BroadwayInChicago.com

for info on this and other Chicago Theater, visit http://www.TheatreinChicago.com