A DIFFERENT KIND OF GAME

Rufus Wainwright received a smattering of awards for his self-titled 1998 debut, loud fanfare for his follow-up album Poses, and his cover of Leonard Cohen’s classic “Hallelujah” for the Shrek Soundtrack in 2001, but has not found the same level of praise or success for his subsequent efforts. Mentions of his name continue to be peppered among classic songwriters like Elton John, George Gershwin, Cole Porter, and Brian Wilson. And there is nary an article that fails to mention his lineage; a child of two highly revered folk music singer-songwriters, Loudon Wainwright III  and Kate McGarrigle. He is also an outspoken activist for gay marriage; married to Jorn Weisbrodt, with whom he shares his daughter, Viva; conceived courtesy of Leonard Cohen’s daughter, Lorca Cohen.

and Kate McGarrigle. He is also an outspoken activist for gay marriage; married to Jorn Weisbrodt, with whom he shares his daughter, Viva; conceived courtesy of Leonard Cohen’s daughter, Lorca Cohen.

Wainwright has been riding on the coattails of his own potential for the last fifteen years. He’s a man who has the talents and qualities of a star, but hasn’t been able to break through in a way that similarly idiosyncratic contemporaries Bon Iver and Sufjan Stevens have. Hitmaker and Grammy Producer of the Year Award-winner Mark Ronson was enlisted to produce Rufus’ latest effort, the ironically titled comeback album, Out of the Game, trading most of his trademark 19th century operatics for 1970s rock and roll with a 21st century sheen and gloss, but this album did not produce any hits.

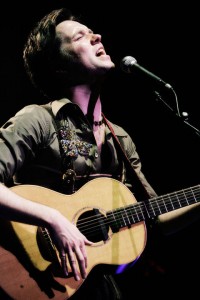

In a ninety-minute concert at Valley Performing Arts Center last week, Wainwright – performing solo, accompanying himself on a concert grand piano and two acoustic guitars – elucidated why he is nearly universally praised for his gorgeous operatic voice, exquisite piano prowess, and inventive, intricately detailed songs. However, his songwriting is often self-focused, and his lofty demeanor can occasionally keep  the audience at arm’s distance. He may have a smaller following than his songs deserve, but there’s no doubt that he’ll continue to be in the game for a long time, no matter how much he thinks he’s out of it.

the audience at arm’s distance. He may have a smaller following than his songs deserve, but there’s no doubt that he’ll continue to be in the game for a long time, no matter how much he thinks he’s out of it.

He swiftly dove straight into the bright and lively “Art Teacher;” his voice nimble and powerful, and his hands moving along the ivories with expressiveness akin to George Winston on his deeply felt yet propulsive Winter record. After that opening song, he admitted that his only knowledge of Northridge was in reference to the 1994 earthquake. Pleasantries and humorous admission aside, he then played the dark and heavy waltz “This Love Affair” and the wistfully spry “Grey Garden.”

“The best part of the show is when I stand up,” Wainwright proclaimed, grabbing an acoustic guitar, and delivering the clever self-effacing eponymous title track of Out of the Game. His voice was looser and more playful, while his guitar work overall  was more like an enthusiastic camp counselor (his piano work is far more accomplished and nuanced).

was more like an enthusiastic camp counselor (his piano work is far more accomplished and nuanced).

He joked afterwards that his latest release didn’t sell well for two reasons: One, it’s hard to get kids to relate to being “Out of the Game,” and the second was because it happened to be released right when a certain “Massive Korean” took the world by storm with “Gangnam Style.” He mused, “So once again, it’s Korea’s fault.”

Next played was “Jericho,” which follows “Out of the Game” on the album as well. It carries soulful echoes of Elton John with its soaring melody and rapturous chorus, which is why I found it curious that this song full of dancing bass notes and octave hopping was relegated to straight guitar strumming; it would’ve had more colors and verve played on the piano.

Back at the piano, he performed the constantly chromatic and jaunty Debussy-flavored “Matinee Idol,” and the plaintive “Martha,” a song written in the style of a voicemail to his sister addressing her absence and insisting she come visit or at least  call him back while he was tending to their ailing mother.

call him back while he was tending to their ailing mother.

It is in the introductions to his songs that Wainwright doesn’t always connect with his audience. Before playing “Gay Messiah,” Wainwright spoke about his experience in Paris where demonstrations were being held in opposition to gay marriage. And while he mentioned the fact he found it disturbing because children and families were out protesting in the streets, his lack of focus and aloof delivery diffused what could’ve served as a powerful set-up for his anthem. There was no fire in his belly or passion roused in the audience after his story. Instead, he told a weak joke that was met with mild laughter. In contrast, I am reminded of the time that Bruce Springsteen tied his personal anecdote about living in the dark, disturbing times of the draft and Vietnam, and how it served as the catalyst for a unique and rare bonding moment with his father. This provided the necessary backdrop that had his audience connected to the working class struggles before he sang “The River.”

Wainwright offered the closest thing to insight when he spoke about Jeff Buckley; He talked about how much contempt he had towards the late singer-songwriter early on in his career struggling in New York. Years later, as Wainwright got his record deal and a great deal of buzz, he returned to New York and played some shows – and Buckley turned up to see him. Through the course of conversation and hanging out with him after the show, Wainwright “fell in love with him,” but Buckley passed away a few weeks later. Written as a tribute to Buckley, Wainwright performed “Memphis Skyline” – an impressionistic, melancholic stream of consciousness piece – with great tenderness and passion; and then the Leonard  Cohen penned “Hallelujah” (which Buckley popularized and Wainwright cemented as an enduring standard) with a beautiful, flowing grandeur and grace.

Cohen penned “Hallelujah” (which Buckley popularized and Wainwright cemented as an enduring standard) with a beautiful, flowing grandeur and grace.

With the operatic and melancholic “Going to a Town,” his voice rode out the whole of his baritone-tenor range with supple ease and fluidity. The similarly despondent “Zebulon” followed and segued seamlessly into the delightfully brisk and busy “Cigarettes and Chocolate Milk,” which succinctly demonstrated his exceptional powers working in full: The words were clever and relatable, the melody sophisticated yet catchy, the music adventurous and tuneful, and the vocal performance had power coupled with cheeky personality. Elsewhere, his vocals were often more focused on being operatically languid than telling the story.

“Montauk,” a playful yet pointed love letter to his daughter, Viva, was the first encore. Then, to promote an upcoming tribute album honoring his mother called Sing Me the Songs, he performed “The Walking Song,” written by his mother and aunt, Kate and Anna McGarrigle. It was a song that stood out: Full of wit,  tenderness, and easy sing-a-long structure, it was also one of the few moments where Wainwright got outside of his operatic rigidity and truly appeared to be having fun. This was followed by the cheeky and charming cabaret torch song “Foolish Love.”

tenderness, and easy sing-a-long structure, it was also one of the few moments where Wainwright got outside of his operatic rigidity and truly appeared to be having fun. This was followed by the cheeky and charming cabaret torch song “Foolish Love.”

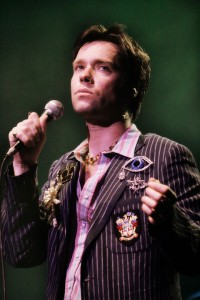

As he played the final number, “Poses,” it served as a reminder of why people root for his success. When he is not so narrowly focused on his autobiographical narrative, it all comes together and he is capable of delivering hypnotically beautiful, accomplished music. His voice live has a presence that has not yet found its way onto recordings. Experiencing Wainwright in this fashion, one is able to hear dimensions not heard in studio efforts. Barefoot and dressed in a black suit that looked like it received some Jackson Pollock action painting, he was dressed just like his music was performed – naked to an extent and outfitted with elegance, with a smash of pop for good measure.

His performance had flashes of cohesive brilliance, a few silly diversions, and even a few flubs, but overall his voice and piano playing were exceptional, and the evening was entertaining.

poster photo by Tina Tyrell

publicity photos by Alex Lake, Barry J. Holmes, Matthias Clamer from RufusWainwright.com

An Evening with Rufus Wainwright

Valley Performing Arts Center

California State University, Northridge

played June 8, 2013

for future events and tickets, visit http://www.valleyperformingartscenter.org/