BY GEORGE, I THINK THEY’VE GOT IT;

THE SCRIPT, HOWEVER’¦

A friend of mine is an Alan Ayckbourn fanatic, owning dozens of the prolific playwright’s scripts, yet he can count on one hand the productions he has seen to date. For him, American productions are never as good as the scripts. Therfore, he says, he’d rather read the prolific British playwright.

I concur with my friend that something is lost in translation when Ayckbourn’s plays hit the States, perhaps due to the subtleties that only an English actor can glean from the mind of an English author. While some may perceive Ayckbourn’s plays to be slight, he is both a master observer of the English suburban middle class and a deft innovator who overcomes the confines of a black box by challenging our notions of space and time—such as with his plays House and Garden, both of which take place concurrently on different stages using the same actors. However, at the Manhattan Theatre Club in New York, the time device of House and Garden could not compensate for the American cast’s inability to overcome the weightlessness of the material. The London production of Communicating Doors (with Julia McKenzie) was a funny, thrilling and optimistic farce in which doors between adjoining hotel rooms served as a mechanism for time travel; and yet the off-Broadway production (with Mary-Louise Parker) felt paper-thin.

Of course, Ayckbourn is at his best when he is shocking or devastatingly funny, such as his trilogy The Norman Conquests, but it is his overall ability to make the commonplace human experience utterly fascinating that explains why he is the world’s most performed living playwright. Ayckbourn’s reputation is well-deserved, regardless of how slight or significant a particular script may be. On stage, however, the Knighted Scribe’s words are deceptively simple, not unlike those of Neil Simon; actors must be grounded in reality for the comedy to soar.

Yanks may be forever challenged to get that British patois down pat (and vice versa, which may explain why recent revivals of Neil Simon in London used American actors). Absurdly enough, probably due to Sir Alan’s astounding body of work, reviewers tend to overpraise American productions, such as last year’s Bedroom Farce at the Odyssey, which was so off-the-mark that it was downright embarrassing.

Yanks may be forever challenged to get that British patois down pat (and vice versa, which may explain why recent revivals of Neil Simon in London used American actors). Absurdly enough, probably due to Sir Alan’s astounding body of work, reviewers tend to overpraise American productions, such as last year’s Bedroom Farce at the Odyssey, which was so off-the-mark that it was downright embarrassing.

This brings us to the Old Globe’s U.S. premiere of Life of Riley, the 74th play of the inexhaustible writer. The device here is that George Riley, a character we never meet, has been given a few months to live, thereby affecting the lives of three couples. Included in these duos are Riley’s doctor, an ex-paramour, a soon-to-be ex-wife, and a philandering best friend. When Riley is cast in a local playhouse production of Ayckbourn’s own Relatively Speaking (his first hit [1965] that also deals with infidelity), the wily Riley uses the situation for manipulative purposes of his own.

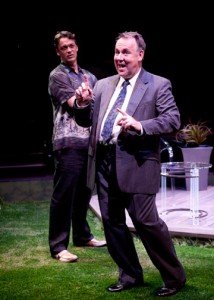

Fortunately, director Richard Seer and his lovely cast have overcome the impediments normally associated with American productions of Ayckbourn’s works—they hit all the right notes, especially Colin McPhillamy as Riley’s doctor, Colin, and Henny Russell as Kathryn, Colin’s wife, who conspires to rekindle an old love affair with Riley by suggesting he be in the community play.

Fortunately, director Richard Seer and his lovely cast have overcome the impediments normally associated with American productions of Ayckbourn’s works—they hit all the right notes, especially Colin McPhillamy as Riley’s doctor, Colin, and Henny Russell as Kathryn, Colin’s wife, who conspires to rekindle an old love affair with Riley by suggesting he be in the community play.

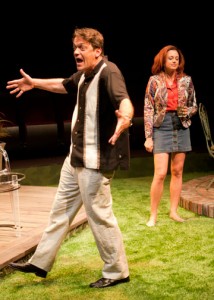

Unfortunately, this play, Life of Riley, is not one of Ayckbourn’s better efforts. True, some of the dialogue is funny (Kathryn notes that conversing with her spouse is akin to “talking through a sheet of glass, as if you’re in prison or at the post office”), and there is no shortage of mistaken motivations, but the structure does not compel—especially due to three underdeveloped characters: Monica (Nisi Sturgis), who left Riley just weeks before his diagnosis; Simeon (David Bishins), the swarthy Scottish farmer with whom Monica now resides; and Tilly (Rebecca Gold), a teenage girl who has almost as much stage time as George Riley (remember, we never meet him).

Mr. Bishins is a perfect example of why Life of Riley neither sizzles nor fizzles: the actor brings strength and vulnerability to what is essentially a thankless role; everything about him screams hardscrabble, hard-working cultivator, but his presence adds no conflict or surprise. When Monica’s sense of spousal obligation sends her to Riley’s side, Simeon’s response is to kick a large tire and go limping offstage. This scene, as with many others, makes the play come off as a very long episode of a British sit-com. It’s a physical bit of business which falls flat and interrupts the flow of the piece, thereby keeping the tension at a minimum.

Mr. Bishins is a perfect example of why Life of Riley neither sizzles nor fizzles: the actor brings strength and vulnerability to what is essentially a thankless role; everything about him screams hardscrabble, hard-working cultivator, but his presence adds no conflict or surprise. When Monica’s sense of spousal obligation sends her to Riley’s side, Simeon’s response is to kick a large tire and go limping offstage. This scene, as with many others, makes the play come off as a very long episode of a British sit-com. It’s a physical bit of business which falls flat and interrupts the flow of the piece, thereby keeping the tension at a minimum.

Some scenes positively crackle: Tamsin (Dana Green) is so furious that her husband Jack (Ray Chambers) is having an affair that she accepts Riley’s offer to take a holiday (read: have an affair of her own); when Kathryn and Monica, who have also been invited on holiday by Riley, meet Tamsin at Riley’s home, the fur really flies. Likewise, the scenes in which Colin and Kathryn rehearse their parts in the community play (only to discover that it mirrors the communication problems in their own marriage) are rife with wry wit.

The result is that Life of Riley is a pleasant afternoon tea instead of a sumptuous feast. It’s a quandary as to whether Seer could have done more with the material. Both the play’s world premiere (at the Stephen Joseph Theatre in Scarborough, directed by Ayckbourn himself) and here in San Diego were staged in-the-round, and Seer’s cast has no problem handling the English idioms and idiosyncrasies. Certainly, the Sheryl and Harvey White Theatre—one of the finest ever built, both for sight-lines and its technical capacity—is perfectly utilized: Robert Morgan’s set of four gardens (and costumes that could be worn in any Ayckbourn play from the 1960s onward) fit the space perfectly, and Paul Peterson’s multi-directional sound is extraordinary.

Perhaps Ayckbourn, who suffered a stroke in 2006, was just feeling a bit more genteel. One can only hope that we will see more of his vulgar villains and biting observational wit in the future—produced with the excellence of The Old Globe, naturally. In the meantime, Life of Riley is a nice diversion, no different than a stroll through sunny Balboa Park where The Old Globe is situated.

photos by Henry DiRocco

Life of Riley

Donald and Darlene Shiley Stage

The Old Globe

1363 Old Globe Way in Balboa Park

ends on June 5, 2011

for tickets, call 619.234-5623 or visit The Old Globe