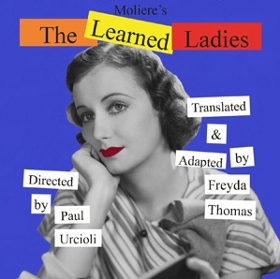

FRANCE: WHERE THE WOMEN ARE WOMEN (AND THE MEN ARE WOMEN, TOO)

Director Paul Urcioli’s delightful production of Moliere’s classic skewering of female emancipation is given an additional dimension of gender politics by the intriguing notion of having all the roles, both men and women, played by female performers who portray the men in drag. Why this should be a shocking innovation is debatable: Back in the day (well, the 16th century, anyway), Shakespeare used to be performed with only male actors and no one shrugged. Indeed, in earlier times, the mere sight of a woman at the theater was enough to cause rage and disgust. It is only until fairly recently, compared to that time, that a woman’s place moved from the bedroom and kitchen – or, rather, out of the back of the cave.

Freyda Thomas’s charming adaptation, which is couched in the rhyming couplets to keep the feel and tone of the original text, sets the work in a 1930s country manor, lending the piece a gorgeously lush glamour. The play centers on the romance between beautiful Henriette (Sarah Brill) and her beloved paramour Clitandre (Marta Kuersten), who want nothing more than to get married. Henriette’s father Chrysale (Elizabeth Neptune) thoroughly approves the match, but her mother Philamente (Madeleine Maby) isn’t as gung ho. Philamente, you see, possesses trendy notions of the roles of women and is herself under the sway of pompous charlatan intellectual guru Trissotin (Katie Honaker), who has created a sort of salon with other members including Phalemente’s daffy sister Belise (Sara Montgomery), and Henriette’s older, spinster sister Armande (Francesca Day). When Philamente plots to marry Henriette to the pretentious scholar, not realizing that Trissotin is a greedy crook and faker, Henriette, Clitandre, and Chrysale are forced to desperate measure to outwit the mother and save the romance.

Freyda Thomas’s charming adaptation, which is couched in the rhyming couplets to keep the feel and tone of the original text, sets the work in a 1930s country manor, lending the piece a gorgeously lush glamour. The play centers on the romance between beautiful Henriette (Sarah Brill) and her beloved paramour Clitandre (Marta Kuersten), who want nothing more than to get married. Henriette’s father Chrysale (Elizabeth Neptune) thoroughly approves the match, but her mother Philamente (Madeleine Maby) isn’t as gung ho. Philamente, you see, possesses trendy notions of the roles of women and is herself under the sway of pompous charlatan intellectual guru Trissotin (Katie Honaker), who has created a sort of salon with other members including Phalemente’s daffy sister Belise (Sara Montgomery), and Henriette’s older, spinster sister Armande (Francesca Day). When Philamente plots to marry Henriette to the pretentious scholar, not realizing that Trissotin is a greedy crook and faker, Henriette, Clitandre, and Chrysale are forced to desperate measure to outwit the mother and save the romance.

Romance is, of course, a central dramatic theme of Moliere’s comedy, but the work is actually also a potent political tract, spoofing the idea of women rising above their station and attempting to shift into worlds that were traditionally male. The female characters seeking education, but being tricked by the loathsome Trissotin, are roundly ridiculed for their naïve foolishness in being swayed by the wrong elements of intellectualism. Although the teasing boasts a layer of bona fide affection, Moliere’s intention is to have us laughing merrily at the notion of these silly women daring to educate themselves, as we ultimately affirm the play’s ultimate moral: There’s nothing wrong with woman being educated, as long as it isn’t excessive and doesn’t injure the male dominated class system and gender hierarchy.

Romance is, of course, a central dramatic theme of Moliere’s comedy, but the work is actually also a potent political tract, spoofing the idea of women rising above their station and attempting to shift into worlds that were traditionally male. The female characters seeking education, but being tricked by the loathsome Trissotin, are roundly ridiculed for their naïve foolishness in being swayed by the wrong elements of intellectualism. Although the teasing boasts a layer of bona fide affection, Moliere’s intention is to have us laughing merrily at the notion of these silly women daring to educate themselves, as we ultimately affirm the play’s ultimate moral: There’s nothing wrong with woman being educated, as long as it isn’t excessive and doesn’t injure the male dominated class system and gender hierarchy.

Perhaps this is why the casting of women in all the play’s male roles adds a soupçon of anger to the comedy. In Urcioli’s assured production, a great deal of thought has clearly gone into how the men should be portrayed. The women performing as the male characters do more than just act out the parts of men here: They attempt to embody elements of male assurance and entitlement, performing them with just a hint of affectation to underline the satiric point. If you don’t think that the notion of women making fun of male arrogance–in a play about men subjugating women–doesn’t make for thematically potent theater, you should probably stick to Neil Simon next time.

Perhaps this is why the casting of women in all the play’s male roles adds a soupçon of anger to the comedy. In Urcioli’s assured production, a great deal of thought has clearly gone into how the men should be portrayed. The women performing as the male characters do more than just act out the parts of men here: They attempt to embody elements of male assurance and entitlement, performing them with just a hint of affectation to underline the satiric point. If you don’t think that the notion of women making fun of male arrogance–in a play about men subjugating women–doesn’t make for thematically potent theater, you should probably stick to Neil Simon next time.

As Chrysale, the father of the house, Neptune, cunningly mannish in 1930s business-wear and slicked-back hair, blusters about like Jackie Gleason, every bit the unassailable Alpha Male. By contrast, Honaker, with half-lidded eyes and a leering mouth, from which a loathsomely wiggling tongue occasionally emerges, is the very image of male promiscuous sleaze in her depiction of Trissotin. In one moment, almost missed if you blink, when Philamente declares that Henriette must marry Trissotin, the sleazy rake quickly turns half-upstage and wriggles his tongue like Ozzie Osborne eating a bat: It’s a deliciously ghoulish sight to see. By contrast, the female-playing-female performers interact with the drag-dudes with a fluttery femininity that artfully hints at the way women of previous eras had to act as satellites to their men. Brill cuts a wonderfully vulnerable and headstrong Henriette, while Maby’s intellectually rigid and emotionally shrill Philamente is a fascinatingly compelling portrait of a modern woman shackled to a subservient society.

As Chrysale, the father of the house, Neptune, cunningly mannish in 1930s business-wear and slicked-back hair, blusters about like Jackie Gleason, every bit the unassailable Alpha Male. By contrast, Honaker, with half-lidded eyes and a leering mouth, from which a loathsomely wiggling tongue occasionally emerges, is the very image of male promiscuous sleaze in her depiction of Trissotin. In one moment, almost missed if you blink, when Philamente declares that Henriette must marry Trissotin, the sleazy rake quickly turns half-upstage and wriggles his tongue like Ozzie Osborne eating a bat: It’s a deliciously ghoulish sight to see. By contrast, the female-playing-female performers interact with the drag-dudes with a fluttery femininity that artfully hints at the way women of previous eras had to act as satellites to their men. Brill cuts a wonderfully vulnerable and headstrong Henriette, while Maby’s intellectually rigid and emotionally shrill Philamente is a fascinatingly compelling portrait of a modern woman shackled to a subservient society.

This is ultimately a Learned Ladies that’s more political than most, but it still offers moments of broad humor and crisp comic timing, though these often seem slightly subordinate to the gender thematics. However, it’s hard not to be impressed by a play that wears its intelligence on its sleeve, in a sprightly, whimsical, and sometimes trenchantly sardonic production that melds wit to farce.

The Learned Ladies

Cake Productions and New Ateh Theater Group

The Abingdon Theatre Arts Complex

June Havoc Theatre, 312 West 36th Street

scheduled to end on October 19, 2013

for tickets, visit Learned Ladies

for more info, visit

http://cakeatehproductions.weebly.com/