A DIFFERENT TYPE OF SOCRATIC PROBLEM

Perhaps one of the reasons Socrates has become a god-like figure in the world of philosophy is that we know very little about the actual man who existed during the dawn of writing. He kept no diaries and wrote no treatises, yet philosophies attributed to the classical Greek thinker’”Socratic Method, Socratic Paradox’”have become a mainstay in modern discourse.

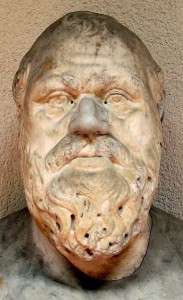

What is certain, according to historians, is Socrates’ provocative personality. Indeed, some scholars maintain that his sentencing to death by an Athenian tribunal had more to do with his “corruption of youth” (read: homosexuality) and his in-your-face approach rather than his actual philosophies (maybe he didn’t write more because he was too busy orally challenging Greek conventions). Plus, if you check out his bust which resides in the Palermo Archaeological Museum, it’s easy to imagine this arrogant ogre-of-a-man spitting his opinions on your neck.

What is certain, according to historians, is Socrates’ provocative personality. Indeed, some scholars maintain that his sentencing to death by an Athenian tribunal had more to do with his “corruption of youth” (read: homosexuality) and his in-your-face approach rather than his actual philosophies (maybe he didn’t write more because he was too busy orally challenging Greek conventions). Plus, if you check out his bust which resides in the Palermo Archaeological Museum, it’s easy to imagine this arrogant ogre-of-a-man spitting his opinions on your neck.

Ironically, he stressed a simplistic way of living, adding that the wisest man is he who claims that he really doesn’t know shit. This idea of a move from self-centeredness and self-indulgence was inherited by one of Socrates’ older students, Antisthenes, who became the originator of another philosophy in the years after Socrates’ death: Cynicism.

Since there are no extensive writings that exist from Socrates himself, what we do know about him comes courtesy of his contemporaries: Aristophanes, the playwright who viciously parodied him in The Clouds (although by all accounts they were friends); Xenophon, a historian who preserved his sayings; Aristotle, the polymath who studied under Plato and went on to tutor Alexander the Great; and  more so than any other, Plato, a student of Socrates who wrote The Last Days of Socrates, a series of four dialogues which describe his trial and death.

more so than any other, Plato, a student of Socrates who wrote The Last Days of Socrates, a series of four dialogues which describe his trial and death.

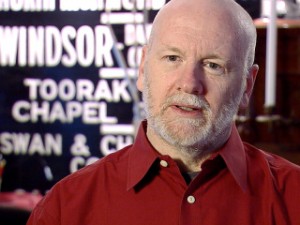

It is the latter which has been turned into a large-scale, one-hour oratorio for orchestra, chorus and baritone soloist, who sings the role of Socrates. Contemporary composer Brett Dean and librettist Graeme William Ellis trimmed Plato’s verbose dialogues into a three-movement shape, beatifying Socrates the philosopher while skirting Socrates the personality. For its U. S. premiere, the work received such an astounding rendering by the LA Phil that it’s a shame to report anything other than complete praise for the overlong piece.

First, the good news: Dean, an Australian former violist from the Berlin Philharmonic (which premiered the work under the baton of Sir Simon Rattle last April), is rightfully gaining attention. He is enthusiastically inventive in Last Days and he is clearly having a blast with unique orchestrations and fascinatingly fun chorale work. Watching the piece being triumphantly tackled by the enormous  orchestra and LA Master Chorale, both of which had sections perform from the “listening area” out-of-sight behind the balcony, it’s no wonder that extra rehearsal time was required, forcing a short postponement of the premiere.

orchestra and LA Master Chorale, both of which had sections perform from the “listening area” out-of-sight behind the balcony, it’s no wonder that extra rehearsal time was required, forcing a short postponement of the premiere.

I’m proud of Gustavo Dudamel for refusing to showcase this complicated premiere last Thursday. Patrons who thought they would see it on the same program with Leif Ove Andsnes performing Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4 that night, found it replaced by an additional Beethoven piano concerto (the No. 2). We were fortunate enough to catch Last Days on a program with Andsnes’s rich and fluid take on the 4, but both programs included the five-minute tasty tidbit, Beethoven’s The Ruins of Athens Overture.

Plato’s work begins with a debate on the nature of holiness between Socrates and a religious expert, “Euthyphro,” which elucidates the Socratic Method. Next, the “Apology” tells of the trial of Socrates as he tears into his accusers and energetically defends himself against charges of heresy; he is sentenced to death by drinking hemlock. In the third dialogue, Socrates, who believes he would be going against his  nature to escape imprisonment, refuses the help of his friend “Crito.” In the “Phaedo,” Socrates discourses on the nature of the afterlife prior to execution; here, Plato promotes his faith in the soul’s immortality: Death should be welcome to the philosopher because it is then that he will attain true wisdom and get rid of the distraction of the body.

nature to escape imprisonment, refuses the help of his friend “Crito.” In the “Phaedo,” Socrates discourses on the nature of the afterlife prior to execution; here, Plato promotes his faith in the soul’s immortality: Death should be welcome to the philosopher because it is then that he will attain true wisdom and get rid of the distraction of the body.

Sounds like it would make a great opera, doesn’t it? That was Dean’s original intention, but now much of the drama has been excised and the four dialogues have been adapted into three movements: The first, “Prelude,” has the tribunal (in this case, the chorale) invoke the Goddess Athena to watch over the trial. The lento but insistent pianissimo opening contains an air of heavenly mysticism courtesy of an electric guitar, accordion and six off-stage violins. As the prelude progresses, there are interruptions of Stravinsky-esque bursts and spider-like strings, as if to indicate the coming storm, climaxing in a forte summons.

Throughout the entire work, the chorus relished their assignment to cluck, clap and hiss, and the five percussionists had a field-day on such unique instruments as terracotta pots and a Waterphone. Even the violins played noisemakers, the basses  used mallots and percussionists bowed their instruments. The display of innovation was gleefully enthralling.

used mallots and percussionists bowed their instruments. The display of innovation was gleefully enthralling.

There were also musical passages, such as a cello cadenza played with mournful elegance by Robert deMaine followed by woodwinds and a rainstick, which called forth a haunting resignation.

But there was a missed opportunity to reinvent the oratorio in Parts II and III, “Apology (The Trial)” and “Phaedo (The Hemlock Cup).” Instead of drama involving arguments and personality, Ellis’s libretto discards characters from the dialogues and indulges in literal Socratisms: “All I know is that I know nothing” and “How we live here decides on that other life” become as wearying as trying to read Plato’s original dialogues. The chorus is relegated to being narrators and spectators when what we need is a less passive Greek Chorus. In the end, Socrates’ request for calm instead brings boredom. To make matters worse, baritone Peter Coleman-Wright lacked power (tenor Joshua Guerrero was twice as commanding in the small role of executioner).

For all the wondrous goings on, I could stomach the troubling libretto. What is inexcusable is this newfangled atonal melody line that is neither minimalistic nor memorable. This inaccessible modern musical style, seemingly de rigueur in new operas, feels like modern composers, after drinking too much of their self-importance, vomit notes willy-nilly onto staff paper. It’s distancing, maddening and clearly unloved by the masses. It speaks volumes how alienating this vocal line is when many spectators were seen exiting Disney Hall at the oratorio’s end without the courtesy of acknowledging LA Phil, the singers, or Dudamel. It is because of the world-class artistry involved that the affair was so amazing to behold, even as the libretto and atonal melodies were all Greek to me.

For all the wondrous goings on, I could stomach the troubling libretto. What is inexcusable is this newfangled atonal melody line that is neither minimalistic nor memorable. This inaccessible modern musical style, seemingly de rigueur in new operas, feels like modern composers, after drinking too much of their self-importance, vomit notes willy-nilly onto staff paper. It’s distancing, maddening and clearly unloved by the masses. It speaks volumes how alienating this vocal line is when many spectators were seen exiting Disney Hall at the oratorio’s end without the courtesy of acknowledging LA Phil, the singers, or Dudamel. It is because of the world-class artistry involved that the affair was so amazing to behold, even as the libretto and atonal melodies were all Greek to me.

photos by Luke Moyer

Los Angeles Philharmonic

Gustavo Dudamel, conductor

Leif Ove Andsnes, piano

Peter Coleman-Wright, baritone

Joshua Guerrero, tenor

Los Angeles Master Chorale

BEETHOVEN: The Ruins of Athens Overture

BEETHOVEN: Piano Concerto No. 4

DEAN: The Last Days of Socrates (U.S. premiere, LA Phil commission)

for future LA Phil events and tickets, call 323.850.2000

or visit http://www.laphil.com/