BLOATED SCORE OR A BIG FAT MUSICAL TRIUMPH?

LA Opera’s production of Verdi’s Falstaff, his last opera which premiered in 1893, fascinatingly elucidates why his one successful comic romp has both detractors and ardent admirers. Those who crave memorable arias will be disappointed, but those who appreciate evocative orchestral music which expresses character and blazes with whimsy will claim this as one of Verdi’s best. I reside between the two.

Shakespeare introduced John Falstaff, that tubby timeworn ne’er-do-well of a knight, in Henry IV Part I; revived his character in Part II; and later used the well-loved scalawag in the comedy, The Merry Wives of Windsor. It is the preposterous plot from Merry Wives that Arrigo Boito uses for the base of his libretto, incorporating some well-known speeches from the Henry plays to enlarge and expand the large and expansive character. Some of the dialogue is truly funny: The  pompous Dr. Caius states that if he ever gets drunk again, it will be in the company of honest, sober men.

pompous Dr. Caius states that if he ever gets drunk again, it will be in the company of honest, sober men.

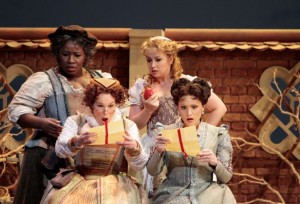

In Acts I and II, Falstaff finds himself pound-free (financially, certainly not physically), so the obese weasel ridiculously sends identical love missives to married ladies Alice Ford and Meg Page, hoping to woo them and thereby win financial favor. When the women learn they have received matching letters, they send neighbor Mistress Quickly to entreat Falstaff to a rendezvous with Alice that afternoon. The Fat Knight gets his comeuppance when he arrives but is thwarted with the unforeseen arrival of Alice’s husband; he is stashed inside a laundry basket and tossed into the Thames by servants.

In the somewhat confusing third act, the disgruntled Falstaff, again at the behest of Mistress Quickly, disguises himself as a Black Huntsman, and arrives at Herne the Hunter’s Oak in Windsor Park to woo Alice one more time. But this time, the company, dressed as fairies, goblins and God-knows-what-all, torments the corpulent rascal until he becomes penitent. And’”just like a 1950s sitcom in which  everyone says wryly, “Oh, that Falstaff!”’”all is forgiven with Verdi’s exhilarating fugue.

everyone says wryly, “Oh, that Falstaff!”’”all is forgiven with Verdi’s exhilarating fugue.

Yes, Falstaff is dissimilar from Verdi’s “big tune” operas, most notably Rigoletto (1851), La Traviata (1853) and Aida (1871), but if you prick up your ears it actually overflows with melodies; too many actually. And when an aria does arrive, it lasts no more than a minute or two. Verdi consistently folds tunes together to the point that nothing truly lands. Let’s just say that musically the opera scarcely ever stands still’”unlike the chorus in the bewildering third act, all of whom remain rather stationary.

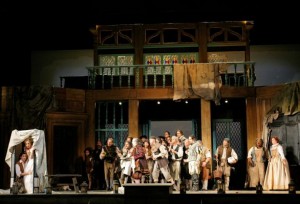

The vision of British director Lee Blakely appears as opera buffa at the Globe Theatre, yet this production isn’t truly funny, mostly because Blakely goes for comic bits such as spit-takes instead of developing humor through characterization. Scenery and costume designer Adrian Linford’s gorgeously and painstakingly detailed set looks like Shakespeare at the Globe, but many of the performers come off like second-rate Vaudevillians (Joel Sorensen, stepping in for Robert Brubaker, plays Dr. Caius like a zombie on cocaine). And you can’t fool an audience in this department: Far and away, the greatest ovations last Saturday were for the two women who never mugged once: robust mezzo-soprano Ronnita Nicole Miller as Quickly and sparklingly light soprano Ekaterina Sadovnikova as Nannetta, Ford’s daughter who is in love with Fenton (Juan Francisco Gatell, beautiful in both stature and voice). Sadovnikova is particularly enthralling in the third act with “Sul fil d’un soffio etesio.”

The vision of British director Lee Blakely appears as opera buffa at the Globe Theatre, yet this production isn’t truly funny, mostly because Blakely goes for comic bits such as spit-takes instead of developing humor through characterization. Scenery and costume designer Adrian Linford’s gorgeously and painstakingly detailed set looks like Shakespeare at the Globe, but many of the performers come off like second-rate Vaudevillians (Joel Sorensen, stepping in for Robert Brubaker, plays Dr. Caius like a zombie on cocaine). And you can’t fool an audience in this department: Far and away, the greatest ovations last Saturday were for the two women who never mugged once: robust mezzo-soprano Ronnita Nicole Miller as Quickly and sparklingly light soprano Ekaterina Sadovnikova as Nannetta, Ford’s daughter who is in love with Fenton (Juan Francisco Gatell, beautiful in both stature and voice). Sadovnikova is particularly enthralling in the third act with “Sul fil d’un soffio etesio.”

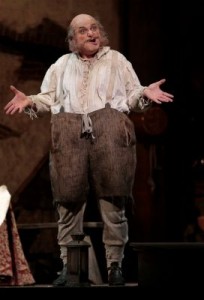

Italian baritone Roberto Frontali’s battered, brusque Falstaff is well-rounded in body and voice, but not character. His physical posturing and hamminess are clear from the back row, but it is unclear whether we should feel pity, sympathy or disdain for  him. Vocally, he never falters, taking his time with the “Honor” aria in Act I (followed brilliantly by James Conlon) and remaining powerful throughout.

him. Vocally, he never falters, taking his time with the “Honor” aria in Act I (followed brilliantly by James Conlon) and remaining powerful throughout.

Linford has a field day with the tattered bodkins of Falstaff and his fellow rogues, but it is the highly textured Elizabethan dresses, the detail of which is reminiscent of miniature portraitist Nicholas Hilliard, that truly steal the eye. The set confuses: Linford has two underutilized Tudor towers bookending the proscenium; both a garden wall and the interior of Ford’s home, however gorgeous like something you’d see at Disneyland, seem to be under construction for no reason; and a huge sail canvas shaped like parchment swoops down with projected Shakespearean monologues on it, but it doesn’t seem to fit the production.

Thus, as it turns out, the best thing about this Falstaff is that score: fascinating for some, impenetrable for others. The singers are terrific’”Erica Brookhyser as Meg, Carmen Giannattasio as Alice, a robust Marco Caria as Ford’”and it’s captivating to listen to the orchestra, especially under Conlon’s astute, muscular and loving leadership (another production of Falstaff was his first professional opera conducting gig). W.H. Auden claimed that Falstaff is a character whose true home is the world of music, and since “music be the food of love” in this production, play on.

Thus, as it turns out, the best thing about this Falstaff is that score: fascinating for some, impenetrable for others. The singers are terrific’”Erica Brookhyser as Meg, Carmen Giannattasio as Alice, a robust Marco Caria as Ford’”and it’s captivating to listen to the orchestra, especially under Conlon’s astute, muscular and loving leadership (another production of Falstaff was his first professional opera conducting gig). W.H. Auden claimed that Falstaff is a character whose true home is the world of music, and since “music be the food of love” in this production, play on.

photos by Robert Millard

Falstaff

LA Opera

Dorothy Chandler Pavilion

scheduled to end on December 1, 2013

for tickets, call (866) 811-4111 or visit http://www.fremontcentretheatre.com/

special concert performance on November 26

Segerstrom Center for the Arts in Costa Mesa