I LOVE LUCIA

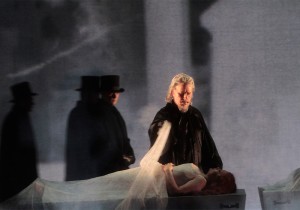

Lucia di Lammermoor, Gaetano Donizetti’s darkly romantic tale of honor, betrayal, loss and madness, opens this Saturday at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion and plays through April 6. Directed by Elkhanah Pulitzer with scenic and projection design by the amazing Wendall K. Harrington (Tony-winner for The Who’s Tommy), this all-new production by Los Angeles Opera features fiery soprano Albina Shagimuratova  in the title role. You will also hear the original scoring for a glass harmonica during the famous mad scene. What it will not feature, fortunately, is most of the source material.

in the title role. You will also hear the original scoring for a glass harmonica during the famous mad scene. What it will not feature, fortunately, is most of the source material.

In the year before his death, English critic and novelist Ford Madox Ford published a 900-page survey of world literature, The March of Literature: From Confucius’ Day to Our Own. In it, he has a few choice words for popular novelist Walter Scott, including the assessment “amateur literary hack.” In referencing Scott’s novels Rob Roy (1817) and Ivanhoe (1820), Ford wrote, “His literary merits are almost undiscoverable ’¦ We are no longer inclined to sit four hours over a book before the author will deign to give us some idea of what his story is.”

I suspect that Salvadore Cammarano had the same thought when writing the Italian language libretto of Lucia Di Lammermoor, very loosely based upon Sir Walter’s sprawling historical novel The Bride of Lammermoor (1819). This tale of a scorned woman who becomes a deranged murderess is pure gothic horror, but it does’”to say the least’”meander, focusing not on the story’s tragic lovers but Scottish politics and daily life at the turn of the 18th century.

I suspect that Salvadore Cammarano had the same thought when writing the Italian language libretto of Lucia Di Lammermoor, very loosely based upon Sir Walter’s sprawling historical novel The Bride of Lammermoor (1819). This tale of a scorned woman who becomes a deranged murderess is pure gothic horror, but it does’”to say the least’”meander, focusing not on the story’s tragic lovers but Scottish politics and daily life at the turn of the 18th century.

This is why Cammarano ignores most of the book, picking up what minor exposition he needs from the first few hundred pages, and going right for the melodramatic stuff in the final chapters that makes opera fun: A woman being forced into a convenient marriage, a ghost, a forged letter, a cemetery, a castle, family feuds, madness, murder, suicide, and a truly insane wedding party.

It is the opera’s wedding party which has become one of the most famous mad scenes in the repertoire. Mad scenes, which contain portrayals of insanity, have always been popular in dramas such as Hamlet, but they became a widespread practice in Italian and French operas during the early nineteenth century. Donizetti loved writing mad scenes, and Lucia’s bel canto breakdown is one of the most famous soprano solos in all of opera. Written for nightingale soprano Fanny Tacchinardi-Persiani, the exceptionally challenging scene is full of vocal fireworks and flowery, embellished vocal lines. Many of the melodies from the opera’s previous songs are warped to show Lucia’s crackbrained condition. The choruses and storyline course unswervingly into Lucia’s double aria and recitative, making this a spooky scene drenched not just in blood but in psychological overtones.

It is the opera’s wedding party which has become one of the most famous mad scenes in the repertoire. Mad scenes, which contain portrayals of insanity, have always been popular in dramas such as Hamlet, but they became a widespread practice in Italian and French operas during the early nineteenth century. Donizetti loved writing mad scenes, and Lucia’s bel canto breakdown is one of the most famous soprano solos in all of opera. Written for nightingale soprano Fanny Tacchinardi-Persiani, the exceptionally challenging scene is full of vocal fireworks and flowery, embellished vocal lines. Many of the melodies from the opera’s previous songs are warped to show Lucia’s crackbrained condition. The choruses and storyline course unswervingly into Lucia’s double aria and recitative, making this a spooky scene drenched not just in blood but in psychological overtones.

Since it was written, the scene has been a showcase for the most technically agile sopranos. L.A. audiences are lucky to get Russian coloratura soprano Albina Shagimuratova, who only recently made her role debut as Lucia during the 2010/2011 season at Houston Grand Opera; of that performance, The New York Times wrote: “Baby faced and clarion voiced, Ms. Shagimuratova was a riveting Lucia, her flighty mad scene the stuff of nightmares.” On Feb. 1 of this year, she became the first Russian soprano to sing Lucia at Milan’s Teatro alla Scala. Here is a recording of Shagimuratova singing the Mad Scene:

Since it was written, the scene has been a showcase for the most technically agile sopranos. L.A. audiences are lucky to get Russian coloratura soprano Albina Shagimuratova, who only recently made her role debut as Lucia during the 2010/2011 season at Houston Grand Opera; of that performance, The New York Times wrote: “Baby faced and clarion voiced, Ms. Shagimuratova was a riveting Lucia, her flighty mad scene the stuff of nightmares.” On Feb. 1 of this year, she became the first Russian soprano to sing Lucia at Milan’s Teatro alla Scala. Here is a recording of Shagimuratova singing the Mad Scene:

Making its return in L.A. Opera’s production is a rarely heard instrument that Donizetti used when scoring Lucia’s descent into battiness’”the glass harmonica. Have you ever run your moistened finger around the rim of a wine glass only to hear a specific musical note? So did Galileo, who first wrote of this phenomenon in Two New Sciences. But it was Irishman Richard Pokrich who created what would commonly be known as the “glass harp,” a set of upright wine glasses, with each glass tuned to a different pitch, either by construction or varying levels of water. The novel instrument met the public in 1741, and found favor when it was played by opera composer Christoph Willibald Gluck, who used 26 goblets for his “singing glasses.” Mozart had actually composed music for the glass harp long before Donizetti.

Making its return in L.A. Opera’s production is a rarely heard instrument that Donizetti used when scoring Lucia’s descent into battiness’”the glass harmonica. Have you ever run your moistened finger around the rim of a wine glass only to hear a specific musical note? So did Galileo, who first wrote of this phenomenon in Two New Sciences. But it was Irishman Richard Pokrich who created what would commonly be known as the “glass harp,” a set of upright wine glasses, with each glass tuned to a different pitch, either by construction or varying levels of water. The novel instrument met the public in 1741, and found favor when it was played by opera composer Christoph Willibald Gluck, who used 26 goblets for his “singing glasses.” Mozart had actually composed music for the glass harp long before Donizetti.

But the clever contraption was difficult to play and travel with. Leave it to Benjamin Franklin and his trademark efficiency to fix the pitfalls of such an instrument. Instead of glasses, Franklin’s contraption, called a glass armonica, mounted a series of shallow, concentrically positioned cast lead glass bowls onto a horizontally spinning shaft that was continuously spun by a handy foot treadle. The bowls graduated in size with each glass replicating a single tone. Since the glass harmonica was arrayed like a keyboard instrument, you could play up to ten notes at one time. Equally inventive was that the spinning bowls continually picked up moisture from a water-filled reservoir beneath them as they spun; forget about having to moisten fingertips.

But the clever contraption was difficult to play and travel with. Leave it to Benjamin Franklin and his trademark efficiency to fix the pitfalls of such an instrument. Instead of glasses, Franklin’s contraption, called a glass armonica, mounted a series of shallow, concentrically positioned cast lead glass bowls onto a horizontally spinning shaft that was continuously spun by a handy foot treadle. The bowls graduated in size with each glass replicating a single tone. Since the glass harmonica was arrayed like a keyboard instrument, you could play up to ten notes at one time. Equally inventive was that the spinning bowls continually picked up moisture from a water-filled reservoir beneath them as they spun; forget about having to moisten fingertips.

The glass harmonica also began to generate public controversy. Sinister rumors began to float around about the instrument’s otherworldly secret powers. The controversial German doctor Franz Mesmer used it to “mesmerize” difficult patients, and the instrument was banned in a few German cities, disappearing in 1835, the same year Lammermoor opened. Even worse for the glass harmonica’s popularity was the rumor that the instrument’s distinctive harmonic overtones drove players and listeners into madness (this may have been true for musicians: The use of lead glass may have led to lead poisoning).

The glass harmonica also began to generate public controversy. Sinister rumors began to float around about the instrument’s otherworldly secret powers. The controversial German doctor Franz Mesmer used it to “mesmerize” difficult patients, and the instrument was banned in a few German cities, disappearing in 1835, the same year Lammermoor opened. Even worse for the glass harmonica’s popularity was the rumor that the instrument’s distinctive harmonic overtones drove players and listeners into madness (this may have been true for musicians: The use of lead glass may have led to lead poisoning).

Since the device was rumored to send one to the cuckoo’s nest, Donizetti exploited it to emphasize the gravity of Lucia’s unhinged state. But for all of its eerie qualities, the disturbing, bizarre, and ethereal tones of Ben Franklin’s glass harmonica were replaced by Donizetti with two flutes, a scoring familiar to most listeners. Under the baton of James Conlon, Thomas Bloch, one of the very few professional “glassharmonicists” in the world, will play with the orchestra in this production. Here is Bloch playing a Mozart composition:

Since the device was rumored to send one to the cuckoo’s nest, Donizetti exploited it to emphasize the gravity of Lucia’s unhinged state. But for all of its eerie qualities, the disturbing, bizarre, and ethereal tones of Ben Franklin’s glass harmonica were replaced by Donizetti with two flutes, a scoring familiar to most listeners. Under the baton of James Conlon, Thomas Bloch, one of the very few professional “glassharmonicists” in the world, will play with the orchestra in this production. Here is Bloch playing a Mozart composition:

This production is filled with breathtakingly beautiful imagery, enveloping the entire stage with an effect that draws the audience right into Lucia’s increasingly maddening world. And with tickets as low as $19 for every performance, everyone can experience the madness and glass harmonica of Lucia di Lammermoor.

photos by Robert Millard

Lucia di Lammermoor

Los Angeles Opera

The Music Center’s Dorothy Chandler Pavilion

135 North Grand Avenue

ï‚· Saturday, March 15, 2014 at 7:30 pm

ï‚· Thursday, March 20, 2014 at 7:30 pm

ï‚· Sunday, March 23, 2014 at 2:00 pm

ï‚· Wednesday, March 26, 2014 at 7:30 pm

ï‚· Saturday, March 29, 2014 at 7:30 pm

ï‚· Sunday, April 6, 2014 at 2 pm

2 hours and 40 minutes, including one intermission

for tickets, call 213.972.8001 or visit www.LAOpera.com