I’M NOT SAYING YOU SHOULD

BE SKIPPIN’ PIPPIN, BUT’¦

Prepare yourself. After all the rave reviews and buzz from New York, Diane Paulus’s Tony-winning revival hits the road filled with enough high-flying frivolity to bedazzle even the most jaded of theatergoers. But for all its extraordinarily magical moments it ends up being a soulless circus due to a problematic book and less-than-magnetic leads. But hey, this is America, where forgive-and-forget audiences will happily trade glitz for storytelling. Just how this national tour resonates is wholly dependent on the viewer.

This powerhouse pumped-up Pippin both explicates and paves over the imperfections in Roger O. Hirson’s libretto about a prince searching for fulfillment in the realm of his father, Charlemagne, a.k.a. King Charles. Constructed like Children’s Theater — although it’s clearly for the older crowd, dealing with regicide, combat, and lust, to name a few — the first act is a chain of scenes (most with a character who appears only once): Pippin as warrior; Pippin as king; Pippin as sex machine.

Act II slows down as the depressed prince attempts domesticity with a widow and her young son. Then he’s back to his futile quest, egged on all the while by a chorus of street performers and the Leading Player, a Sportin’ Life emcee who devilishly urges Pippin to explore facets of life that, once discovered to be empty, may lead the youth to despair and maybe even suicide.

It’s actually an ordinary musical, even with the charmingly palatable melodies and engaging lyrics by Wicked’s Stephen Schwartz. Without a distinctive style by a director who plays up the darker themes of depression and angst, Pippin feels like the weakling musical that can be beat up by Annie. Bob Fosse’s original 1972 production — which got more than a few kids, including myself, addicted to theater — added enough pell-mell diabolical dazzle that the feeble book became one colorful, magical, musical, rhythmic body. Theatrical legend has it that Fosse fought against an intermission; money-hungry producers wanted revenue between acts, but Fosse knew that audiences, realizing there was no there there, would continue past the merchandise directly to a taxi.

Here, there’s so much going on that the added intermission is almost mandatory. Paulus tapped circus genius Gypsy Snider of the Montreal-based company 7 Fingers (Les 7 doigts de la main), and the adroit acrobats perform Cirque du Soleil-style feats of derring-do that enhance the unique theatricality of Pippin’s journey. The band of storytellers assisting the Leading Player are transformed here into a cast of pole-climbers, hoop-jumpers, and assorted circus-troupers whose astounding antics are played out on Scott Pask’s big-top set. Act I’s downside, if you can call it that, is that the repetitive brilliance of any Cirque show can become enervating without an engaging story. Thus, the 78-minute first act feels like an enchanting eternity.

Paulus also enlisted Chet Walker, who danced in the original, to choreograph in the Fosse style: his sensual and sexual work is executed best by Sabrina Harper as Fastrada, Pippin’s conniving stepmother. A consummate triple-threat, the leggy, lithe Harper summons the spirit of Fosse better than the acrobats do — all are charming and move well but some lack the Fosse finesse; still, it’s great to see that simple, stylish bump-and-grind again.

And while the visuals never bore, some songs are upstaged by the staging: While recuperating on the widow Catherine’s estate from a failed sense of self, Pippin bemoans that he’s too “Extraordinary” for menial tasks. Feathers fly fast and furious as animals flutter about the barnyard, but the shtick doesn’t stick and — as in other scenes — there is so much going on that we don’t know where to look. As such, a great song doesn’t land. Fortunately, Kristine Reese as Catherine stays grounded enough to hold our attention.

The talk of the town will no doubt be Andrea Martin as Pippin’s grandmother, Berthe. The feisty, voracious Berthe sings of life’s simple pleasures (“No Time at All”) as the audience is encouraged to join in the chorus. The number has always been a showstopper (ask anyone who saw the great Irene Ryan in the original), but here, a buff performer takes the 67-year-old Martin to the air, where she even delivers a verse hanging upside-down. Sadly, this audience favorite is Martin’s only number, and she spends the better part of the show hanging backstage.

Another casting coup is that Charles is now played by the original Pippin, John Rubinstein, who offers his king with a perfect blend of sprightly wackiness and earnest earthiness.

No doubt, Paulus capably uses her three-ring rouser to take a trite tale and launch it into space. Unfortunately, her two leads don’t sparkle as they should. Matthew James Thomas, who created the titular role and left the Broadway cast last March, stepped in at the last minute for this tour when Kyle Selig (Book of Mormon) took a medical leave of absence for vocal rest*. The athletic Thomas, who also played Peter Parker in Spider-Man: Turn  Off the Dark, no doubt brings youthful exuberance, arrogance, and wanderlust to the directionless man, but he is consistently one-note in the pouty department, and frankly seems tired.

Off the Dark, no doubt brings youthful exuberance, arrogance, and wanderlust to the directionless man, but he is consistently one-note in the pouty department, and frankly seems tired.

Bringing down the entire affair is Sasha Allen as the Leading Player (the role which brought stardom and a Tony to Ben Vereen). This gender-neutral role is the show’s core, but Allen, a back-up singer who placed in the top 5 on NBC’s The Voice, lacks both the gravitas and the Broadway chops necessary to come off as life’s number one temptress. She’s toned but not a dancer; and she has a distinctive vibrato but offers some of the worst breath control and phrasing I have ever heard in a Broadway show. It’s disconcerting at best when she breathes in between syllables. This role is way beyond her means, and it begs the question why producers saw fit to cast her. In the attempt to carbon copy Broadway, where a black actress (Tony-winner Patina Miller) also played the part, they sacrificed a third of what this show needs to soar — the other two being design and direction.

I still have a soft spot in my heart for Pippin. While the storyline basically remains unconvincing, the timeless parable of simplicity triumphing over the desire for more remains persuasive. Born in the year that disillusionment with politics, Watergate, and the Vietnam War was growing thick, America was rethinking her gung-ho egocentrism, and a show which parodied the futility of war, power, and the burgeoning sexual revolution in a stylized but darkened Vaudevillian context was, for audiences anyway, a breath of fresh air, running a whopping 1,944 performances.

But the radical counterculture of the 1960s — evident in the fabulous falderal of Fosse’s Pippin — would soon give way to the ubiquitous happy, yellow smiling face of the 70s — evident in this lighthearted rendition. Paulus’s eschewing of the shadowy element for a hyper-presentationalism made the second act “detestable” for one friend (his word; I actually enjoyed the latter half more).

I love the existential message here, which is practically Theater of the Absurd: Looking for meaning in a meaningless existence is futile; extraordinary satisfaction can be found in accepting life’s absurdity. As per Pippin’s grandmother, life — or in this case a Broadway spectacle which lost magic on the road — is merely a brief gift to be enjoyed as best one can.

photos by Terry Shapiro and Joan Marcus

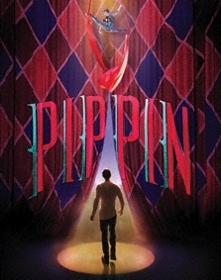

Pippin

national tour

reviewed at Pantages Theatre in Hollywood

ends on November 9, 2014 in Los Angeles

tour continues through 2016

for dates and cities, visit Pippin the Musical

[*Editor’s Note: The Nederlander Organization and the producers announced on Oct. 30 that Kyle Dean Massey, who recently played the role of Pippin on Broadway, will be replacing Matthew James Thomas, who leaves the tour on Nov. 2. Also, Lucie Arnaz will replace Andrea Martin as Berthe beginning Nov. 11, 2014.]

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

What makes PIPPIN viable today isn’t Paulus’s cirque flourishes. It’s the relevance and relatability of its lead character and his journey. Never before has middle-class American youth been more lost and in search of a cure for their widespread and well documented ennui. With high drop out rates, high job dissatisfaction, low voter participation, serial hook ups and — like Pippin — still living at home with a divorced parent, today’s youth are tired of mindless American competitiveness. I loved the show and found it to be deep, thought provoking and highly entertaining.