A BRIDEGROOM ROBBED OF ITS CHARM

Anxiously anticipating The Robber Bridegroom at International City Theatre (ICT), I felt like an excited bride who had already slept with her soon-to-be husband, but found on the wedding night that her bridegroom was cold, unimaginative, and flaccid. If every bridegroom on the planet had the qualities of Todd Nielsen’s production, even heterosexual marriage would be outlawed. How is it possible to take one of the sweetest musicals ever written and turn it into one of the most unfocused and incredibly unfunny evenings in memory?

Mr. Nielsen is no theatre slouch and it seemed like the man could do no wrong since I first came upon his genius in 1982, so there may be stronger forces at work here, namely Actors’ Equity and the cost-cutting efforts of regional houses.

You should know that The Robber Bridegroom is a largely unknown, sparkling, tongue-in-cheek Broadway musical that can be summed up as an enchanting bluegrass folk tale. Based on a Eudora Welty novella, the refreshingly sly account of a two-faced bandit on the Natchez Trace has a quirky, charismatic, comical book and delightful lyrics by Alfred Uhry (of Driving Miss Daisy fame) and an ingenious country score by Robert Waldman, which is tuneful, beguiling, and out of the ordinary – it calls to mind early Appalachian music, but avoids the trappings and banality of country.

My first experience with this piece that celebrates the lustiness of the Mississippi Territory came at a college performance in 1978, two years after Barry Bostwick won a Tony for his performance as the gentleman robber on Broadway. (One year before that, an unknown Kevin Kline starred in a year-long national tour; a two week stop of that same tour in New York earned another unknown her first Tony nomination: Patti LuPone).

Since my first outing at a CSUN, whether at a storefront or regional theatre, the libretto and the stylized, improvisational trappings therein never failed to delight and amuse. (Uhry’s Tony-nominated 1975 book was up against Chicago and A Chorus Line, so what’s a first-time playwright to do?)

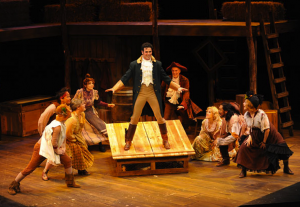

The unusual story has an even more unusual and experimental context: according to Uhry, the piece is one long country dance with various characters calling different parts of the action, much like a square dance caller prompts to the beat of the music. Thus, we begin in some Mississippi barnyard in 1942 where lead players and a large chorus (egregiously cut from this production) set about to tell us outrageous folk stories, settling on Welty’s account (which takes place in 1795) about rascally crook Jamie Lockhart (a perpetually plasticene performance by Chad Doreck), who intends on relieving rich planter Clemment Musgrove (a perfectly cast Michael Stone Forest) of his treasures. Lockhart prefers to “steal with style” and permeates the home of Musgrove, inhabited by his bored but willful daughter Rosamund (bright and beautiful newcomer Jamison Lingle) and her jealous and hideously lustful stepmother, Salome (a bounteously talented but insanely unamusing Sue Goodman).

Intertwined with the leads is the kookiest coterie of characters ever concocted: an inept, pea-brained, hired assassin named Goat (Adam Wylie, whose multi-octave voice is such a unique instrument that it should be preserved for posterity); his backwoods, trashy Mama (Teya Patt); ham-fisted bandit Little Harp, who carries the living head of his brother Big Harp in a trunk (Michael Uribes and Tyler Ledon); and a talking Raven (Tatiana Mac).

This unique musical is primed to be staged in a (what-was-then) nascent American form: Story Theatre. Since all that is required from the authors is an expansive playing space, it is the actors who become not just the peaty swamps and fertile forests, but the cute critters that dwell within. By excising the ensemble, usually eight or more performers, Nielsen has effectively made his main players serve double-duty as chorus, frantically frolicking freely about with no sense of atmosphere whatsoever (to wit, a few actors were noticeably panting after scene changes).

For what purpose was this expurgation done? Was this Nielsen’s vision? I suspect that ICT, once one of the most inventive, cutting-edge companies in Southern California, has fallen into the hands of necessity-over-art. Can they not afford a larger cast? More and more, especially in companies with Equity contracts, cast sizes are shrinking. Could it be that Equity’s financial demands are dictating creativity? Is this an Equity issue? Only four of the nine actors are in Equity, so what prevented ICT from bringing on eight more non-Equity ensemble members? Will Equity not allow it?

ICT, as with other mid-sized, special Equity-contract houses, is in a troubled economy: perhaps they are financially beholden to an unpredictable subscription audience, forcing their hand to choose smaller casts, even as production values remain impressive. Whatever the reason, this production simply smacks of corner-cutting, both in the presentation and the rehearsal time needed to make it work.

Yet imagination costs nothing. One need look no further than local companies such as Anteaus, Rogue Machine, and Boston Court to know that great art is not dictated by budget. Indeed, the last season at ICT was particularly uninspiring and lacking in substance overall. That’s not to say that Robber can’t be done with a smaller cast, but the dull affair here feels slipshod and hastily thrown together, with little attempt at inventive business or a stylized ambiance. Is it coincidence that this critic has not seen a packed house at ICT this entire past season? Whatever happened to, “If you build it, they will come?”

Budget woes also point to the pecuniary restraints of the musicians: the estimable Gerald Sternbach does wonders by manifesting a much-needed honky-tonk on the piano, but there is no piano in the score. Yet another lure of this show is the on-stage string band, which can also be a part of the business, but that, too, was cut in half (still, admirably played by Roman Selezinka, Gary Lee and Brad Babinski on strings). When you substitute piano for mandolin, the score no longer emulates Mississippi’s Rodney’s Landing of 1942 as much as it does The Country Bear Jamboree at Disneyland. (Neither, by the way, did we sense a flavor of Welty when actors mingled with the audience beforehand using modern vernacular).

Plus, somebody (sorry, Mr. Sternbach) forgot to tell the actors that, much like the Carter Family, a vibrato has little to no place in original Bluegrass Music. Singers should hit a note just slightly flat and slide up to true pitch, or pitch songs toward the high end of one’s vocal range, without straining. Also, the exquisite, moody harmonies were handled well by the players, but they were swallowed up and hollowed out by the lead voices.

Even with the huge issue of the truncated chorus and band set aside, Nielsen’s direction was uncharacteristically sloppy and unfocused – you rarely knew where to look on stage as actors scurried like prairie dogs at the site of a hawk. Nielsen either phoned in his direction (a common problem with overworked mid-size and Equity-waiver directors), or he could only do so much with what he had.

As Lockhart, Doreck’s charisma doesn’t make it past the first row because it is a surface, presentational charm. Naturally, he is appealing (why else would he come in third on NBC’s Grease contest?), but we need an actor who is not just magnetism cubed, but can handle the demands of the score – Doreck sounds as if he is singing from his throat, abdicating any opportunity to add inflection. He may steal with style, but he certainly didn’t sing with style.

One good thing that came from the missing assembly of background players was that the haunting ballad “Deeper in the Woods” was handed over to the quirky Mr. Wylie, who brought an entrancing spookiness to this lovely melody. Still, his transformation from the bleating simpleton Goat to lyrical singer was disconcerting.

The powerful pipes and commanding presence of Sue Goodman serve the songs of Salome well, but her line readings were strangely devoid of invention and humor (although her Broadway-style belting was also incongruent to the Hillbilly-styled music). Thank goodness for the beguiling Miss Lingle, whose Rosamund was thoroughly captivating; her winsome, gentle, and assured interpretation of “Sleepy Man” validates why this is one of the best ballads ever to come from Broadway.

Unfortunately, the title of that song also referred to a saddened critic in the audience.

photos by Carlos Delgado

The Robber Bridegroom

International City Theatre

Long Beach Performing Arts Center

300 E. Ocean Blvd. in Long Beach

Thurs – Sat at 8; Sun at 2

ends on November 6, 2011

for tickets, call 562.436.4610 or visit ICT