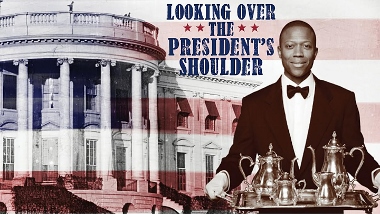

PRESIDING OVER HISTORY

This is a discovery-rich, impeccably presented journey through our political past: American Blues Theater’s Looking Over the President’s Shoulder takes audiences on an invaluable 80-minute tour of the White House, unlike any we ever could. Smoothly written by A.B.T. artistic affiliate James Still and cogently directed by Timothy Douglas, this one-person one-act reprises the omnicompetence and piercing observations of Alonzo Fields, a witness to American history at its most domestic.

The grandson of a freed slave, Fields was a butler (finally chief butler, like Carson at Downton Abbey) at the White House from 1931 to 1953. The majority of his social service was for Democrats (Roosevelt and Truman), bookended by two Republicans (Hoover and Eisenhower). He saw, and through Manny Buckley’s masterful performance, tells us, the best and worst about four pre-war, war and post-war presidents. As with Lee Daniels’ The Butler, Still’s reclamation effort, based on Fields’s memoirs, restores and confirms the personal price behind public events: We grasp conditional change and idiosyncratic impulses, fascinating revelations that contrast what happened with what might have been.

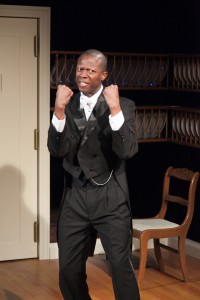

Brian Sidney Bembridge’s very serviceable set consists of racks and racks of White House china: A chandelier-lit dining room in the background suggests the East Room. His resonating foreground is a room for remembrance. Buckley does the rest, beautifully. His narration displays the same grace, gravity and assurance that Alonzo Fields displayed, supervising crucial or intimate state and family dinners during a Depression, a hot and a cold war. Fields, to whom politics was always people, saw the veneer of civilization, as much as the trappings, and the pain behind the protocol.

Tellingly, Fields, born in 1900 and dying in 1994, never wanted the eminence he achieved. From his youth, in an all-black town in southern Indiana, his dream was to be an opera singer. But hard times required quick money. A minister’s connection to Mrs. Herbert Hoover led to a two-decade, upstairs/downstairs gig. It put Fields literally behind American and foreign icons’”Presidents, first ladies, Winston Churchill, movie stars, labor leaders, closeted Ku Klux Klanners, captains of industry, movers and shakers.

Tellingly, Fields, born in 1900 and dying in 1994, never wanted the eminence he achieved. From his youth, in an all-black town in southern Indiana, his dream was to be an opera singer. But hard times required quick money. A minister’s connection to Mrs. Herbert Hoover led to a two-decade, upstairs/downstairs gig. It put Fields literally behind American and foreign icons’”Presidents, first ladies, Winston Churchill, movie stars, labor leaders, closeted Ku Klux Klanners, captains of industry, movers and shakers.

Fields was there to see and hear gossip about whether a “cripple” could be elected Chief Executive (he was right and they were wrong); the chaos of Pearl Harbor Day; Eleanor’s quiet anguish when F.D.R. died before the war could; the moment in Fort Lauderdale when Churchill coined the phrase “Iron Curtain” before introducing it to the public; Erroll Flynn acting like the jerk he was; the great soprano Marian Anderson singing at the White House but not allowed to dine there; and the proper way to discourage visitors from absconding with White House “souvenirs” such as spoons and porcelain. Throughout, Fields’s goal was “to help make history,” if only by getting out of the way when not needed–and in the way when he could make a dynamic difference.

We encounter the proper, puritanical, tee-totaling Hoovers, where servants would hide in a closet to escape detection; the pell-mell Roosevelt clan and how Eleanor, not wanting the help to be hidden, let him use the elevator; how his favorite President, Harry Truman, embodied heartland integrity and fairness in person and in public (he desegregated the Armed Forces); and, finally, Alonzo Fields’s affecting farewell to 104 famous rooms as he says goodbye to “Ike” and returns to Boston and the rest of his life. (We learn little about his family, other than that his wife bossed him around as he did the 6 butlers and 16 cooks of the White House staff.)

Betraying too much personal pride and common sense to be an Uncle Tom, Fields is never less than intriguing as he marvels at the seamless transitions of presidential power–how he could serve breakfast to one Presidential family the morning of January 20th and dinner to another one with a very different concept of cuisine.

Betraying too much personal pride and common sense to be an Uncle Tom, Fields is never less than intriguing as he marvels at the seamless transitions of presidential power–how he could serve breakfast to one Presidential family the morning of January 20th and dinner to another one with a very different concept of cuisine.

Fields never got to be an opera singer, though his happiest memory was in 1936 when he got to perform informally in the White House, the chief occupants not, however, present. Happily, for us, Buckley feelingly and totally recalls seminal close encounters with greatness and pettiness. He shares these with spontaneous and invigorating directness and sincerity. We’re present at a lot of creation.

photos by Johnny Knight

Looking Over the President’s Shoulder

American Blues Theater

Greenhouse Theater Center, 2257 N. Lincoln Ave.

Thurs-Sat at 7:30; Sun at 2:30

Sat at 3 on Feb 27 & March 5

ends on March 6, 2016

for tickets, call 773.404.7336 or visit American Blues Theater

for more Chicago Theater, visit Theatre in Chicago