AN EX-SLAVE BREAKS NEW CHAINS

Eager to be relevant but not quite succeeding, Thomas Klingenstein’s Douglass, a world premiere by the american vicarious at Theater Wit, is nonetheless a valuable historical allegory. An exercise in irony as much as reclamation, it depicts the struggle of a 19th-century American emancipator, not just to find freedom from slavery, but freedom after slavery. Frederick Douglass escaped from Mr. Covey, the taskmaster he knocked down, but in the antebellum era he becomes a sympathetic symbol and lecturer against slavery, not the writer and leader he knows himself to be.

Klingenstein presents, rather statically despite a plethora of plot, three responses to the “peculiar institution” whose ending will require over 600,000 deaths in the decade to come. Refusing to compromise with evil, firebrand Boston editor William Lloyd Garrison (Mark Ulrich) and his Liberator want the North to separate from the South. But for all his radical zeal, Garrison has less respect for blacks as citizens than he has rage for them as chattel. Douglass, who wants to run his own newspaper, is quick to see this liberator’s hypocrisy. But he needs this mentor nonetheless, as well as literary patrons like a shipyard owner’s niece (Carrie Lee Patterson) and an English white lady Julia Griffiths (Saren Nofs Snyder) with whom he has an affair (and, though the play doesn’t mention it, a child).

Anticipating Marcus Garvey, the second reaction comes from Delany (Kenn E. Head), a black power prototype if not embryonic Black Panther. Refusing the pity of philanthropy and thwarted in his desire to become a doctor, he refuses to trust white people. He wants his fellow sub-citizens to emigrate to Africa. He considers Douglass an Uncle Tom (like the then-current book) whose meliorating approach to a national disgrace is temporizing, slow and spineless.

Caught in their crossfire and refusing to be anyone’s “minstrel,” Douglass (De’Lon Grant, giving a skittish performance on opening day) finds himself trapped between Garrison’s abolitionist absolutism and Delany’s staunch separatism. Refusing to give up on America, he unconvincingly argues that, despite its declaration that a black man is 3/5 of a human, the Constitution is an anti-slavery document. It only needs to be enforced to end injustice and inequality. African-Americans must not only be freed from shackles but from the stigma of slavery. (He gives a whole new meaning to “Slow and steady wins the race.”) Champing at the bit to make his mark, Douglass wants his own press in order to prosecute that principle. To get it and a larger audience, he will neglect his faithful Anna (Kristin Ellis) for the patronage of white bluestockings and charitable benefactors.

Once these three positions are presented, Klingenstein unspools the early years of Douglass’s long and complex career, abruptly ending each act as if to show the arbitrariness of the action. Douglass’s dealings with entrepreneur Davis (John Lister), who hates slavery but doesn’t like “Negroes,” flesh in more contradictions for Klingenstein to italicize. Most wrenching here (in the writing more than the acting) is the rift between a manipulated Douglass and his father-figure Garrison, who ends up smearing his protégé for his affair with a British patroness.

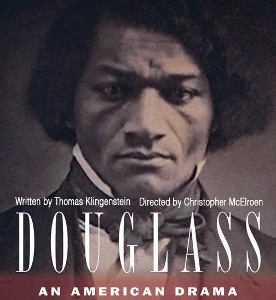

A multi-media masterpiece, Liviu Pasare’s period projections and Sarah Espinoza’s contemporizing sound design (including chants from Trump fanatics) provide urgency to Klingenstein’s reconstruction, more so than does Christopher McElroen’s staging, alternately declamatory or jittery. Douglass’s stubborn efforts to become his own man come off more as an abstract evolution than a timely example of political co-option and exploitation.

To the play’s credit, it asks a necessary question to indict today’s factions: What best sways men’s souls’”reason or feeling (Hillary or Trump)? No question, Douglass’s unfinished journey from chains in Maryland to meetings with Lincoln remains a very American odyssey. But with perverse success Douglass manages to preserve it in amber and under glass.

photos by Evan Barr

Douglass

the american vicarious

Theater Wit, 1229 W. Belmont Ave

ends on August 14, 2016

for tickets, call 773.975.8150 or visit Theater Wit

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

Good to read reviews of the Douglass play and how it reveals his complex relationship with Garrison: The constitution viewed differently by both men, the British role in helping Douglass, both add up to a history not very well known.

Thank you Tom Klingenstein for illuminating us this summer in Chicago. Perhaps the play will be produced in NYC and Boston? Or to Waterville or even Monmouth, Maine?