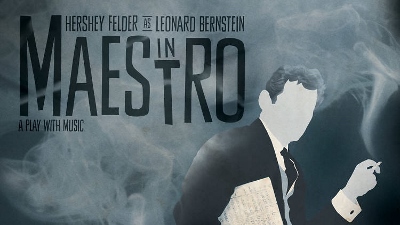

BRINGING BERNSTEIN TO LIFE

Older spectators will remember Leonard Bernstein not just as a conductor, composer, and pianist, but as one of the most vivid personalities and astonishingly effective communicators in the history of American classical music. His life may have ended on notes of regret and frustration, but he was a one-of-a-kind phenomenon, and Maestro does well to bring him alive at the Wallis, even if it is at times overwrought and overly reverential.

Writer/performer Hershey Felder’s impersonation may not reveal the man in all his complexity, but the stage is held for 100 minutes, thanks to Felder’s multitasking as a pianist, actor, and sometime singer. Except for a silvery wig, he isn’t made up to look like Bernstein, but his voice and intonations sometimes sound like Bernstein and his piano skills are well up to fleshing out Bernstein’s talents as soloist and composer.

On François-Pierre Couture’s set that—given the old cameras and Christopher Ash’s multimedia of rolling clouds—looks something like a 1960s television studio in heaven, Felder/Bernstein addresses the audience directly. It’s best not to question the setting of Felder’s many one-man composer recreations but the location here is ambiguous. Ultimately, it’s not important whether this is Bernstein’s last gasp before his death in 1990 or a return from the grave; the audience is entertained with a survey of his life and insights into classical music.

Indeed, much of Maestro, helmed by Felder’s long-time director Joel Zwick, focuses on Bernstein’s skill at explaining classical music to a non-specialist audience. There is one particularly dramatic explication of the “Liebestod” from Richard Wagner’s opera Tristan and Isolde that conveys Bernstein’s passion for music, feverishly dramatized by Felder’s over-the-top piano playing in synchronization with recorded orchestral accompaniment (the levels of Erik Carstensen’s sound design of both soundtrack and voice mic are perfect).

Whatever the circumstances of the scenario, at least the format is easy to follow. Felder begins with Bernstein’s early life, especially his difficulties with his orthodox Jewish Ukrainian immigrant father, who was not enthusiastic about his son’s decision to follow a musical career. There is also a dramatic rendering of Bernstein’s big career break at the age of 25, when, at the last minute, he was called on to replace the ailing Bruno Walter as conductor in a Sunday afternoon concert by the New York Philharmonic. Bernstein’s nationally broadcast performance instantly made him famous and secured his place in the American classical music world.

Among his other achievements, Bernstein was a great raconteur, a gift Felder humorously captures in Bernstein’s account of his first meeting with the notoriously dour conductor Fritz Reiner. And while the show skirts Bernstein’s politics, it is refreshing to witness his notorious temperament when Bernstein explodes in anger over a ridiculing article by Tom Wolfe about his wife, Felicia Montealegre, and a controversial description of a fund raiser for the radical Black Panther Party in Bernstein’s home.

The narrative drive in Maestro isn’t that strong, except for Bernstein’s early relationship with his dad and in the last third of the one-act show when there is a glimpse into Bernstein’s shabby treatment of Montealegre: the bisexual Bernstein abandoned her and his three children to run off with a male companion for a year. (The “play with music” skirts Bernstein’s bisexuality even more than his politics.) The recollections end with Bernstein’s outburst of indignation at his lack of acceptance as a composer. He craved a place in the pantheon of classical music composers but had to settle on being remembered in the popular mind for his work for the Broadway stage. Bernstein may have been comparing his output with the oeuvre of the great composers (his admiration for Mahler is keenly felt here), but it seems difficult to fathom that West Side Story and Candide—benchmarks in musical theater history—are works he considers something for which he must settle.

Maestro is another of Felder’s one-man shows about famous musical figures—George Gershwin, Frederic Chopin, Ludwig van Beethoven, Irving Berlin, et al. Maestro presents a generous helping of Bernstein writings from both his Broadway and classical output, but very few will be familiar to the average listener beyond the excerpts from West Side Story. Passages from the Jeremiah symphony, Mass, and his piano sonata are interesting but they don’t catch the ear like the other composers he has enacted.

I noticed very few, if any, patrons under middle age in the audience. Felder does attract the senior crowd, which revels in reminiscence. Those unfamiliar with Bernstein are advised to arrive early. For several minutes before the show begins, the attentive viewer can absorb a film projected on the upstage wall showing Bernstein delivering one of his inimitable TV discussions of classical music. Ignore the audience conversation as patrons settle into their seats, and you will truly see Bernstein’s charisma and stage presence, as well as his genius at analyzing the heart and soul of classical music for the layman.

photos courtesy of Hershey Felder Presents

Maestro: A Play with Music

Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts

9390 N. Santa Monica Blvd. in Beverly Hills

ends on August 28, 2016

for tickets, call 310-746-4000 or visit The Wallis