DESIRING MARTHA GRAHAM

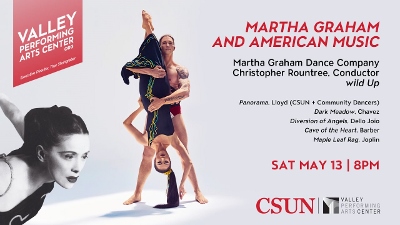

Presented at the Valley Performing Arts Center, Martha Graham and American Music took five dance pieces from within the Dance Company’s repertoire and matched them to live accompaniment by the L.A.-based music collective wild Up and its conductor Christopher Rountree. The result was a testament to Graham’s modern-day relevance as an artist, enhanced by a universal theme that bound all five, distinct stories together: Human desire’”alternatively presented as dark, heavy, light-hearted and comic, but always as demanding.

This VPAC season closer served as an introduction to the dance company and by extension contemporary ballet. The selected works that made up the evening were simple and strong pieces that flaunted some of Graham’s signature choreography, love, mythology along with a self-parodying number, which grounded her seriousness in laughter.

The show began with Graham’s 1935 piece, Panorama. The work, presented by 28 dance students from CSUN and local LA high schools, is grounded in militaristic marching and high knee lifts set to dramatic drumming (music by Norman Lloyd). Initially explained by Artistic Director Janet Eilber as being based in social activism, and the exploration of space and geometric patterns, the movement is mainly based in fluid groups that would alternatively take center stage to form a shifting panorama of people.

When briefly broken away from the group, individual dancers poise their arms in different positions around their body and head, rather than continuing to move as one entity, showing off the individual’s role for the first time in the routine. Their costumes were all the same red material that stuck out boldly in communistic unity against a blue backdrop and emphasized their final army-like formation with arms outstretched in a victorious “V” as they geared toward revolution and change.

Dark Meadow Suite, first commissioned in 1946, is about desire and seeking. Inspired by the time a young Graham spent with the Southwest Pueblo and Mexican Native Americans, the piece concentrates on six women dressed in earth tones whose movements’”as with Panorama’”are very regular and unified. However, their regular pattern of stomps and community-based rituals are quickly interrupted by scantily clad men who steal the stage as they bring a conflicting element of desire into the women’s lives.

The men’s poses are confident, slapping their thighs loudly as some women take turns dancing with the four newcomers. Much of the focus is on the men’s strength and ability to lift or lead their partners. The music peeks and falls dramatically, mimicking the progression of their dances as the men determine their wants and needs. Harmonized movements are contrasted with sharp, full-body extensions wherein the women lean away from their partners. Set to music by Carlos Chavez, the dance never reaches a solid conclusion as the main couple remains on stage alone as Lorenzo Pagano, the Adonis-like figure, strongly holds Anne O’Donnell, his mate, by her ankles, longingly looking up at her as she reaches outward, continuing to roll her hands in waves as if swimming away from him.

With Diversion of Angels, the evening’s themes grow more passionate and concrete, aided by a score by Norman Dello Joio. This 1948 work explores love expressed either three different women or possibly one woman in three stages in her life. Color differentiates each character’s frame of mind: yellow represents school-aged flirtatiousness and indecisive love (Laurel Dalley Smith); red is romantic love, which often comes across as lust (Anne O’Donnell); and white is mature, spiritual love (Leslie Andrea Williams). The light, romantic music depicts their moods as they shift between their male companions and other potential love interests.

Smith most often hides her face while skipping across the stage and exchanging looks with male dancers. Her appearances are whirlwind and fleeting. O’Donnell, equally quick, is sometimes hard to distinguish from Smith, who she occasionally mirrors side-by-side. Much of her time is spent in the arms of men who lift and spin her around; she gets lost in turbulence more often than her yellow counterpart, her performance climaxing with erratic rolling on the floor. She occasionally crosses paths with her better, wiser half in white, only staying temporarily within their shared routine while Williams carries on without her. Williams is Diversion of Angels’ indisputable star. Her posture is tall and her strides confident as she places her body up against her partner (Abdiel Jacobsen) in a warm hold. Despite being surrounded by temptation, she chooses to ignore other men, concentrating on her duet with Jacobsen, who does the same when it comes to other women. In the end, they are the only couple to be shown fully embracing one another as partners.

Cave of the Heart (1946) encompasses the most somber plot. Set to Samuel Barber’s music, the story revolves Medea (Xin Ying), a sorceress who in a fit of obsessive and vengeful rage murders her old lover Jason (Ben Schultz), his new wife, the princess of Corinth (Charlotte Landreau), and (not explicitly shown on stage) their two children. Props play a significant role in this take on the ancient Greek myth: A wire tree acts as a vessel that switches between protecting Ying when she is vulnerable and inhibiting her when she is forced to depart in the end. Similarly the makeshift throne serves to emphasize beats in the story’”at one point, the chorus (Konstanina Xinatra) throws herself over the structure after realizing that she can’t prevent the horrific events from unfolding.

Although there is no mystery involved in the conclusion of the piece, Medea’s desire to be with her former lover allows for an array of movement that is more plot-driven and dark when depicting the first death, that of the princess. She is dragged onto the stage in a sheet, which is unceremoniously pulled off of her to reveal her unmoving form. This contrasting presentation of the dark side of love adds to the shock value of Cave of the Heart while enriching the sweetness and desirability of Diversion of Angels.

The final work which came at the end of Graham’s repertoire, 1990’s Maple Leaf Rag, is the best way to highlight Graham’s tropes, including dramatic extensions, stoic expressions, and serious overtones complete with familiar angular arm and leg movements. These artistic choices may seem foreign to first-time viewers, but they helped Graham stick out from the beginning of her career.

The piece is a mish-mash of characters who appear in familiar-looking costumes to mock the character of the choreographer herself, frustratingly trying to come up with something new. The dancer here sits on a wide bar, sometimes moving along to the pleasant and active scene around her, but often brooding with lack of inspiration. The music, played live by pianist Richard Valitutto, is Scott Joplin’s masterpiece after which the ballet is named. Moments interrupting the fluidity of Graham’s thoughts are portrayed with heavy tones banged out on the keys, which often announce the appearance of dark characters that cross the stage in over-the-top slides and spins.

Closing with Graham’s spoof of herself not only lightens the mood from Cave of the Heart, but also reaffirms the entire show by embodying desire as the aspiration to create. Coupled with the seamlessness with which the new music matches and outlines the dancing, it has the ability to trigger the audience’s personal desire to research more Graham on their own and return to new shows in the future.

photos by Luis Luque

Martha Graham and American Music

Valley Performing Arts Center

18111 Nordhoff Street in Northridge

played May 13, 2017

for tickets, call 818.677.3000 or visit VPAC

for more info, visit Martha Graham