THORNTON WILDER’S SURVIVAL SAGA

It’s a play for all seasons and all sorrows: Writing during the uncertainty of a world war, Thornton Wilder intended The Skin of Our Teeth to be a three-act reassurance. A promissory note to be redeemed during misfortunes, it would remind mortals of their better angels. This winner of the 1943 Pulitzer Prize might, he hoped, offer a blueprint for a worthy peace. When better to create one than when we’re threatened with—whatever? Only during war can we dream of a better world: In peace, comfort is the main consideration.

It’s a play for all seasons and all sorrows: Writing during the uncertainty of a world war, Thornton Wilder intended The Skin of Our Teeth to be a three-act reassurance. A promissory note to be redeemed during misfortunes, it would remind mortals of their better angels. This winner of the 1943 Pulitzer Prize might, he hoped, offer a blueprint for a worthy peace. When better to create one than when we’re threatened with—whatever? Only during war can we dream of a better world: In peace, comfort is the main consideration.

Knowing that “every good and excellent thing in the world stands moment by moment on the razor-edge of danger,” Wilder’s troubled and embattled Antrobus family embody the human race as they (barely) endure an ice age, a great flood, and global war. The first, set in Excelsior, New Jersey, requires sacrificing the dinosaurs and mammoths to shelter humanity from walls of ice (it gives new meaning to “keep the home-fires burning”).

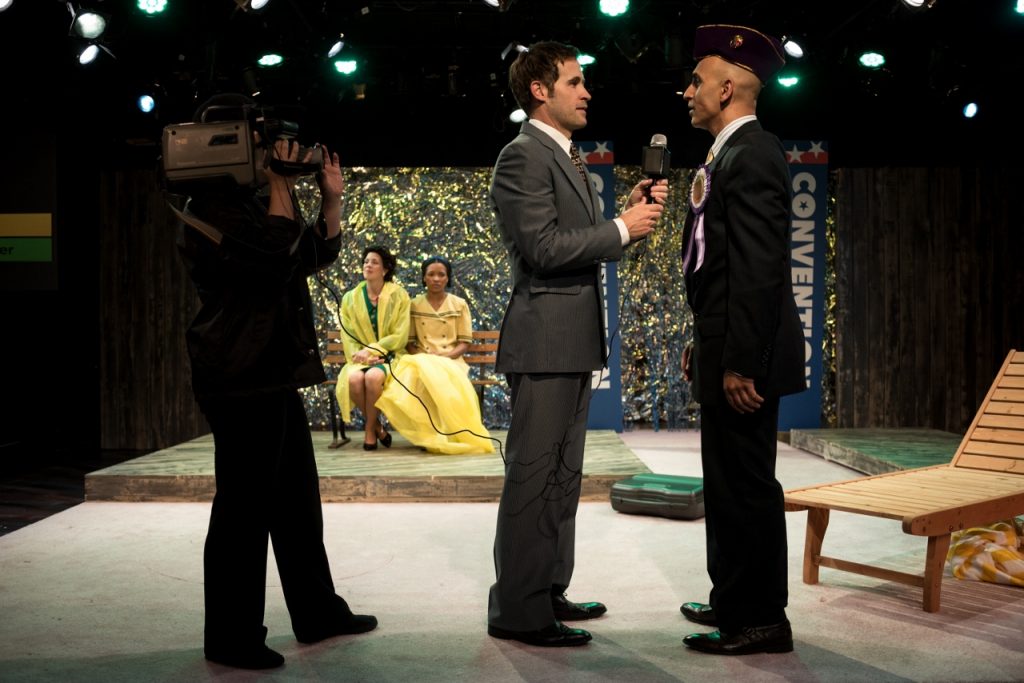

The second scrape with catastrophe, set in a convention-al Atlantic City complete with beauty pageant, requires humankind to rise above sectional and sexual disruptions to escape a rising ocean. The hurricane that hits here seems perversely and prophetically familiar. So does a short-sighted hedonism that puts the present before the future.

The too-contemporary final fight depicts the aftermath of world conflict, where our species’ chief hope is to preserve the wisdom of the centuries (beautifully compared by Wilder to the hours of the night and the planets of the solar system—the music of the spheres). As Wilder knew, “the great ’˜unread’ classics furnish daily support and stimulation even to people who do not read them.”

The too-contemporary final fight depicts the aftermath of world conflict, where our species’ chief hope is to preserve the wisdom of the centuries (beautifully compared by Wilder to the hours of the night and the planets of the solar system—the music of the spheres). As Wilder knew, “the great ’˜unread’ classics furnish daily support and stimulation even to people who do not read them.”

It’s all too easy to project disasters that Wilder couldn’t contemplate—global warming, climate change, and nuclear war—onto his all-purpose template for struggle and survival. Few plays have grown so well and truly into the future. As with Our Town, Wilder’s imperishable distillation of the American (and human) experience, The Skin of Our Teeth (alluding to how close we’ve come to annihilation) is a gloriously cautionary consolation, as wise as it is wary (“The glory of the stage,” he wrote, “is that it is always ’˜now’ there”). The universal is in the particular and no good deed goes unwitnessed.

A force for progress despite his doubts, Mr. Antrobus is the inventor of the alphabet and the wheel—and he’s not through yet tinkering us into civilization. He protects refugees and cherishes the books that made and keep us human. He sees the family as a unit of persistence but not the greatest reason for prevailing against calamity. Faithful to a fault, his wife, intrepid and doggedly literal-minded, fiercely defends her difficult children—Gladys, demure and unfinished, and Henry (formerly Cain), a testosterone-ridden alpha male with an urge to kill.

Shrewdly and warmly, Wilder transforms what could have been a sententious lecture into a playful and presentational play. Through the saucy maid Sabina (who believes in survival at any cost and without any cause), we’re constantly confronted with the play’s “meta” artificiality. Wilder wanted it to feel like an improvisation, which is exactly how humanity would have to cope with these crises. This dramatist is always willing to play with his play, as well as cast and audience.

Shrewdly and warmly, Wilder transforms what could have been a sententious lecture into a playful and presentational play. Through the saucy maid Sabina (who believes in survival at any cost and without any cause), we’re constantly confronted with the play’s “meta” artificiality. Wilder wanted it to feel like an improvisation, which is exactly how humanity would have to cope with these crises. This dramatist is always willing to play with his play, as well as cast and audience.

The trick for any production is not to compete with the play’s own irreverence. A very welcome 75th anniversary production from Remy Bumppo Theatre Company, Krissy Vanderwarker’s staging, now playing at Chicago’s Greenhouse Theater Center, cleverly moves us from the stereotypical 50s to the laid-back 70s to an apocalyptic present. Whatever the trappings, it never reduces these archetypes to cartoons. It trusts the text, up to and including the bittersweet and highly conditional end.

Delivering a running review of the show even as she performs in it, a pert and impertinent Kelly O’Sullivan’s Sabina turns every strategic snafu and putative reversal into the laughter of relief and recognition. Kareem Bandealy’s dour Mr. Antrobus is nicely contrasted to Linda Gillum, implacably maternal as the protective Mrs. Antrobus, who is also invincibly proto-feminist (she says of women: “We’re not what you’re all told and what you think we are: We’re ourselves.”) Kayla Raelle Holder and Matt Farabee steep their very different siblings in contagious cruxes of adolescence.

Threatening the uneasy cohesion of the Antrobus clan are the challenges of infidelity and adultery (which Sabina incarnates in the second act, set on the famous “boardwalk” during a Noah-like convention of mammals) and free-floating violence (embodied by the always discontented Henry, the anarchist within).

Beyond this nuclear family, however, Wilder honors the supporting cast we call humanity, including the stage manager and the actors playing these characters. Vanderwacker’s terrific ensemble triple up as an all-purpose Announcer (Annie Prichard); Cassandra-like fortune teller (Charin Alvarez, prophesying as if pre-inventing Game of Thrones); a Flintstones-like dinosaur (Kristen Magee); and such worthies as Homer (Diego Colon), Moses (Michael McKeogh), and a Muse (Alice Wu).

It’s nearly three hours of sweetly subversive entertainment, an irresistible charmer not afraid to ask hard questions or offer intriguing solutions. Our “eternal family,” as he put it, has never so needed Wilder’s rueful comforts or ethical encouragement. He knew that this play “mostly comes alive under conditions of crisis.” Right now it couldn’t be more required.

The Skin of Our Teeth

Remy Bumppo

Greenhouse Theater Center, 2257 N. Lincoln Ave.

Thurs – Sat at 7:30; Sun at 2:30

plus Wed at 8 (Oct. 25, Nov. 8)

and Thurs at 2:30 (Nov. 2)

ends on November 12, 2017

for tickets, call 773.404.7336

or visit Remy Bumppo

for more shows, visit Theatre in Chicago