IS THAT ALL THERE IS?

For his intriguing but overlong new work Second Quartet, which received its U.S. premiere at The Wallis last weekend, young French choreographer Noé Soulier writes in the program about his 28-minute piece: “Without the spectator having to recognize the motivations behind these complete movements, they are intended to stimulate his or her own physical memory by appearing directed or defined by something that is invisible. This openness allows images, physical expectations, and other associations to inform the spectator’s perception of the movement itself.”

After about 10 minutes, I gave up trying to perceive anything here, or for that matter the entire Fall Program of L.A. Dance Project, a five-year-old company which has taken up residency here at The Wallis in Beverly Hills. This was an evening of dance for dancers’ sake: The ten movement artists and their choreographers may have an idea what’s going on, but we don’t. We may love some of the moves and the sheer athleticism of the skilled dancers, but after a while this kind of dance would have far greater impact if it tried to be more adventurous, or tried better storytelling, or offered a different type of choreography altogether—something to break up the modern dance monotony. While it may be possible to superimpose some kind of meaning behind the moves, ultimately it’s all about the moves. Which is why modern dance can be so tricky.

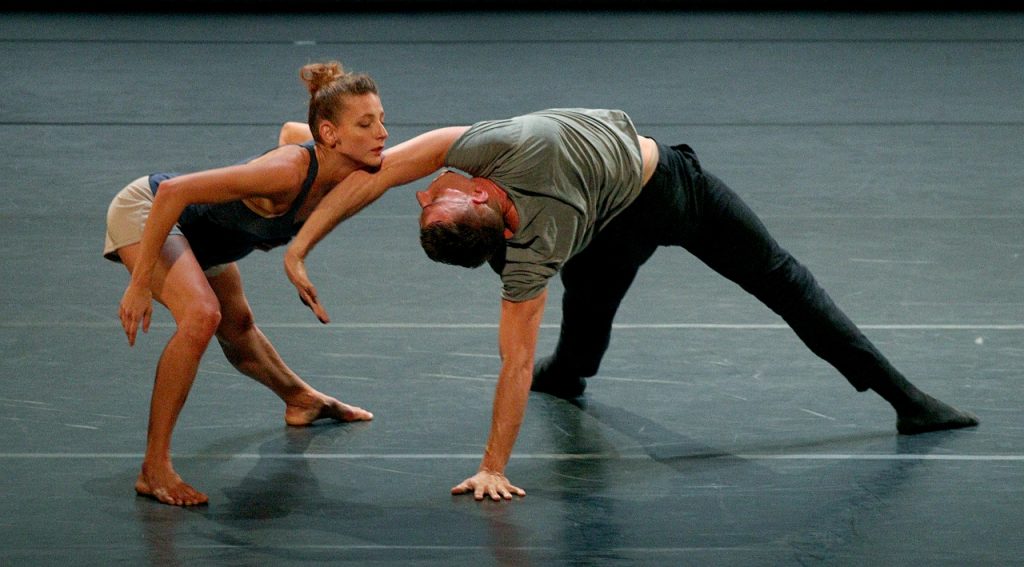

What I saw in Second Quartet was four dancers (Nathan Makolandra, Rachelle Rafailedes, Aaron Carr, David Adrian Freeland, Jr.) throwing a lot of percussive movement at us (many repeated time and again): mule kicks, karate thrusts, head swings, hip thrusts, foot stomps, sauntering, and occasionally something literal such as soccer or basketball maneuvers. Like whirling electrons, the idiosyncratic performers—whether barefoot or in stocking feet—were a pleasure to watch as they fell to the floor or created a series of slow poses or braced their partner or sometimes just tacitly took stock in each other.

What began as exciting, captivating, and fascinating repetition—aided by Tom De Cock and Soutier’s taped minimalist percussion and Victor Burel’s silhouetted lighting—soon became repetitiously mundane, lacking humor and surprise (except in the few pratfalls at the beginning; those, too, lost their appeal).

The other three pieces were created by Artistic Director Benjamin Millepied, whose work fits squarely into modern dance, is moving further and further away from the classical ballet we saw in his work in the past, yet there a few remaining signs of Robbins and Balanchine, but that is disappearing as well. His works are becoming more and more sporadically organized with no signature style. As usual, his work here is either strangely unemotional, meandering, or lacking in clarity. The first few times I saw his work, I thought there’s nothing wrong with watching an interesting series of fluctuating bodies seemingly used for nothing more than visual effect, but now it’s time for reinvention.

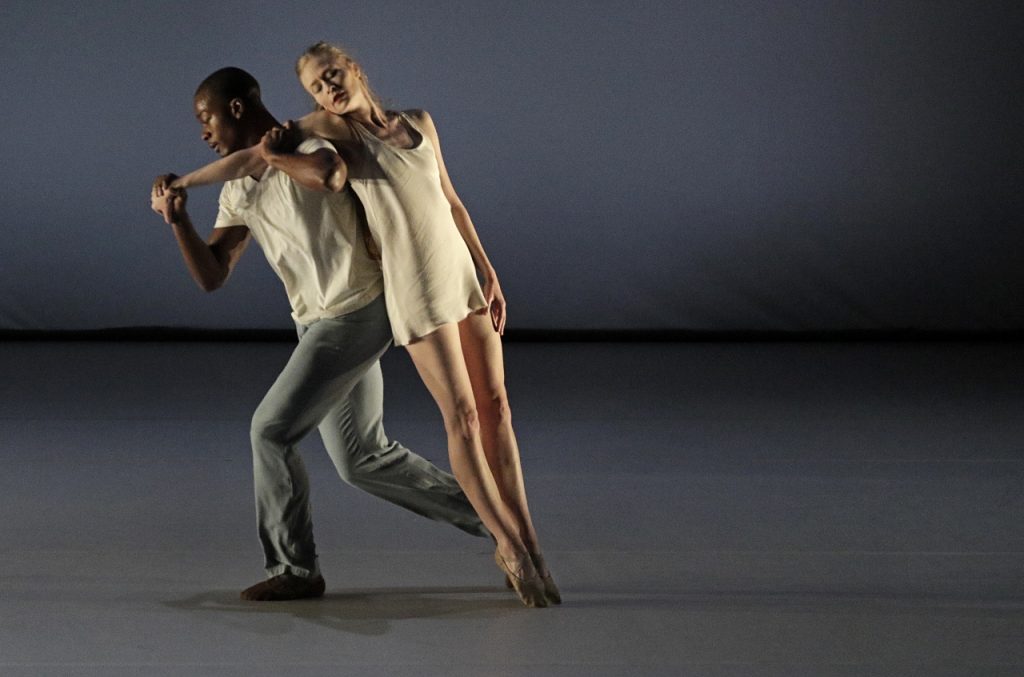

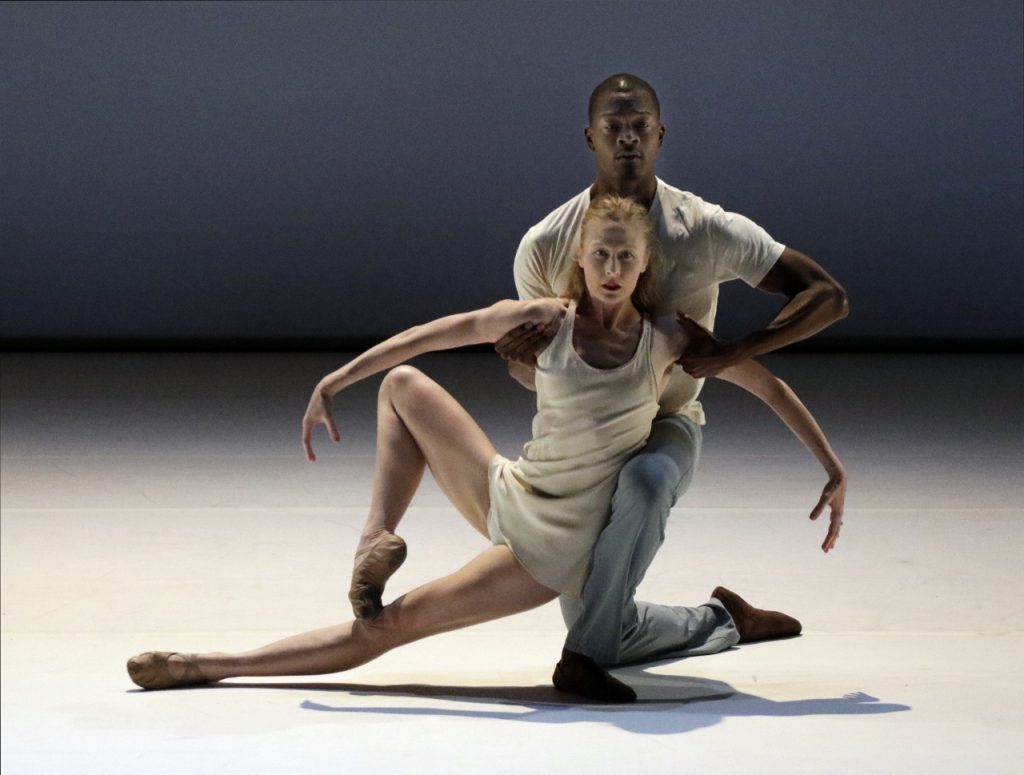

I enjoyed his opening piece most. Closer, a 16-minute L.A. premiere, is an exquisitely romantic pas de deux for David Adrian Freeland, Jr. and Janie Taylor, perfectly suited for each other given his major upper body strength and her supple litheness. Always in close supportive contact—whether strolling, reflecting, skipping, or waltzing; tame or wild with an occasional hesitancy—the lyrical, lovely couple presented their geometric love affair, keeping it so intimate as to make us feel like we’re prying. And even when the lovers disconnect, their moves remain synchronized. Often lit in pale amber by Roderick Murray, the pièce de résistance here was the great pianist Richard Valitutto playing live Mad Rush for piano by Philip Glass.

Opening the third act was In Silence We Speak, another pas de duex but for two women. Taylor returned with Rafailedes for what seemed like another ode to lovers, but it’s actually a paean to friendship (the 15-minute piece, which premiered last June at The Joyce, was created for best friends Taylor and Carla Körbes). Set to three David Lang works, the loose-haired women walk, console, and share while wearing loose-fitting jump suits and, seemingly for no reason, tennis shoes, which you can imagine limits the possibilities here—especially in the extensions and lines. (Who cares that these odd unbecoming costumes came from Ermenegildo Zegna by Alessandro Sartori?) It’s surprising how feeble and uninteresting it all turns out to be.

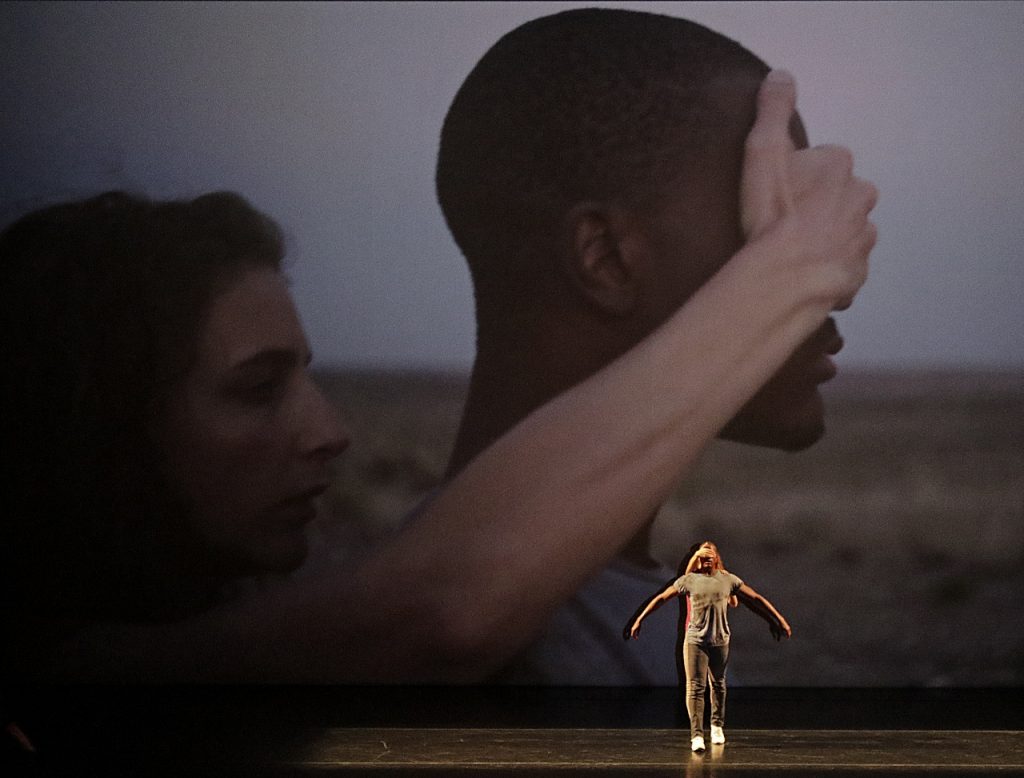

Orpheus Highway, set to Steve Reich’s Triple Quartet, had an amusing set-up which equally failed to live up to its potential. This newer work, which also premiered earlier this year, is both a filmed and danced effort. It somewhat hints at the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice— there are some perceptible storytelling moments but it’s limited. I hear it was filmed in Marfa, Texas, where Giant was made; we can clearly see the desert, a freeway, and an old railway yard. Except for an homage to Robbins’ West Side Story, the dancemaking was unremarkable, messy, and too opaque. The dancers’ moves on film were repeated by live dancers on stage, but they couldn’t compete with that giant screen, which easily usurped their presence.

The dictionary defines “Project” as an individual or collaborative enterprise that is carefully planned and designed to achieve a particular aim. For the life of me, his work doesn’t feel structured or constructed for anything but moving around. I can’t figure out Millepied’s choreography, and I don’t get his aim.

photos by Lawrence K. Ho

L.A. Dance Project

Fall Program

Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts

Bram Goldsmith Theater

9390 N. Santa Monica Blvd in Beverly Hills

ends on November 4, 2017

for tickets, call 310.746.4000 or visit The Wallis