LOVE AND “COMPASSIONATE SILENCE”

We are living through an era that seems to value greed, hypocrisy, narcissism and blatant dishonesty over truth and meaning. This makes the journey into the world of Aaron Posner and Chaim Potok’s The Chosen that much more satisfying. It feels as impactful as a dear friend’s determined embrace, the kind that quiets mere anxiety, allowing tears to finally flow. Each of its four characters is passionately intent on finding what is authentically in his own heart and soul. No vain concerns about spin control or taking the easy way out enter into the picture, and as a result, the virtues of love, spiritual study, and genuine acceptance of others’ differences rule the day. It is profoundly moving, and equally thought provoking.

Based on Potok’s international best-selling 1967 novel, playwright Posner worked both with Potok to adapt it for the stage in 1999, and with Potok’s widow, Adina, to further develop the version used in this production. It is a classic “talk” play, with no small amount of narration from among the cast ’” and in director Simon Levy’s inestimable hands, its traditional form feels vital, alive, and important.

It is the story of two boys from different worlds who find themselves with one another’s help. One is Hassidic, destined to follow in his father’s footsteps as a charismatic rabbi. The other is a secular Jew whose father is a liberal professor. Both fathers seemingly live lives of the mind, but their inner lives guide them towards understanding their sons, as both boys mature and choose paths at odds with what their families intended.

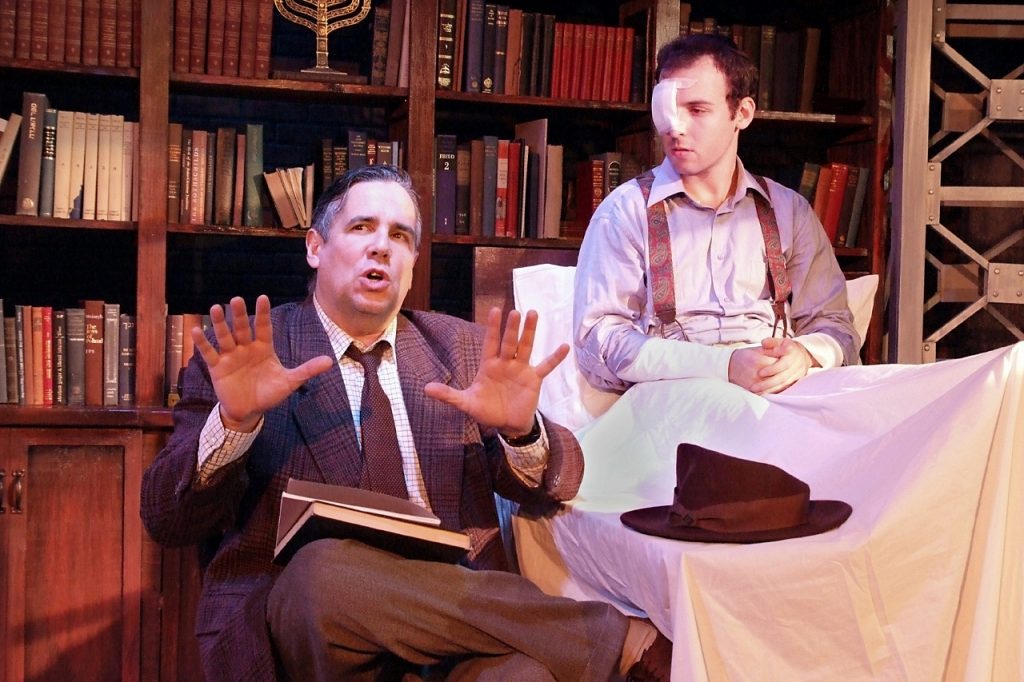

Reb Saunders (Alan Blumenfel) has chosen a life of personal silence with son Danny (Dor Gvirtsman). While they speak passionately about scripture and rabbinical interpretation, they have virtually no direct communication. It drives Danny crazy ’” he cannot understand why the father he so loves and respects would treat him in this way, but feels proscribed from directly asking for answers, and he is scared to share his profound interest in Freud.

Danny’s unlikely friendship with Reuven (Sam Mandel) provides a bridge. Saunders communicates obliquely with his son through Reuven. The war ends, the Nazi genocide of the Jewish people is fully revealed, and the formation of the Zionist movement splits apart the Jewish community. Reuven finds himself drawn to a spiritual life, rather than to the professorial ambitions held for him by his father David (Jonathan Arkin), who has become a passionate advocate for a Jewish state. David’s activism enrages Reb Saunders, who views the spectre of a country led by secular Jews as sacrilege.

At another time in my own life, and perhaps, at another time in our cultural history, I might have felt little sympathy for Reb Saunders fundamentalism or for Danny spiritual and familial dilemmas. Yet, I found myself deeply affected by their journey. Blumenfeld is a marvel. His size and strength commands attention, while his delicacy gives voice to the silence between him and his son. He is driven by conscience and love to make the inexplicable seem rational, essential even. When I was Danny’s age, I would have hated this bombastic man of showy religiosity and entitlement. Now I am moved by the ferocity of his concern, even while recognizing how unbearable it would be.

As Reuven’s father, David, Arkin deftly shifts from the funny, loving single parent to a believable firebrand ’” a man determined that his people should survive and flourish. His deep bond with Reuven is never in doubt. Whether or not he will truly understand his son is more of an open question.

Sam Mandel is our way into the world of the play. He provides most of the narration, jumping in and out of the action seamlessly. His goodness and humor are a great asset to the play, and he can be forgiven for occasionally calling to mind a young Woody Allen.

Dor Gvirtsman is astonishing. His Danny emerges as a brilliant, angular, unpredictable mass of confused loyalties and diametrically opposed certainties. The character and the actor come together to embody Potok’s theme: Ayloo ve’ayloo deevray elokeem chai’eem – “Both these and these are true.”

Under Simon Levy and dialect coach Andrea Caban, the New York and Eastern European accents are as consistent as they are richly enjoyable. Levy has also given great attention to how these characters inhabit space; how they move and how they dress. Hair and makeup by Linda Michaels is equally effective. Turning modern hair to Hassidic and back again is no mean feat.

Peter Bayne’s original music and sound design ably support the production, though I might quibble with the volume and placement of some of the baseball effects. Lighting by Donny Jackson is also a success, giving form and definition to DeAnne Millais’s sturdy set, allowing it to encompass many different realities.

This production resonates on so many levels. For me, it is both antidote and bittersweet reminder of what our society has lost in its race to exalt the lowest common denominator. Yet it also depicts an intensity of family life that I, and I suspect most of us, have never experienced. As I left the theater, I found myself shocked to realize I was jealous of both boys. I’d have taken either one of those dads. Though I’m not sure I would ever have been happy wearing the curly sideburns known as payot.

photos by Ed Krieger

The Chosen

Fountain Theatre, 5060 Fountain Ave.

Sat at 8; Sun at 2; Mon (Pay-What-You-Want) at 8

ends on March 25, 2018 EXTENDED to June 10, 2018

for tickets ($20 to $40), call 323.663.1525 or visit Fountain Theatre