THE PLEASURES OF WEBFOOT COCKLEWOMEN

AND MINCED CAT

Under Milk Wood is a vivid combination of poetry, drama, and music that was first performed as a radio play in 1954, and it is squarely rooted in language. Set in a seaside town in Wales called Llareggub (“bugger all” backwards), it is described as a place where bedroom walls are lined with “glasses of teeth and yellowing pictures of the dead,” attics are not dark, they are “Bible-black and airless,” and a sailor  remembers his, “one love in a sea life that was sardined with women” in a village of “webfoot cocklewomen” and “tidy wives.”

remembers his, “one love in a sea life that was sardined with women” in a village of “webfoot cocklewomen” and “tidy wives.”

My favorite parts of the Open Fist Theatre Company’s production at Atwater Village Theatre are all to do with death. I imagine that says more about me than it does about the play. Or maybe it doesn’t. The rest of the audience seems just as eager for the more macabre bits: A blind sea captain remembers a lost love who calls to him and his drowned pals, “Come on up, boys, I’m dead!”; a husband in a loveless marriage orders away for a book on poisons and remembers “ground glass as he tumbles his omelet”; a neat freak calls her two dead husbands to her bedroom every night to give them chores; and butcher tantalizes his wife with dinnertime tales of mincing the neighbors’ cats and serving them up as beef.

The play is a classic of sorts — Our Town with an earthier, more jaundiced view of humanity, though both share a sense of hopefulness that the human spirit will, if not prevail, at least live to see another day, another year, and so on. People behave in ways that belie their inner desires, whether it is the prudish schoolmistress who secretly wants to be ravished, or the town roué who happily dreams of his mother playing “This little piggy” with his toes.

Open Fist does an excellent job with the material. At eighteen actors, it has one of the largest casts I’ve ever seen assembled on a 99-seat theater stage. Yet a lot of shape-shifting (sometimes mid-scene) is still necessary. The play has almost forty characters. It is an ambitious undertaking for any company. The cast is largely quite effective, though varying levels of skills and experience are evident. For some, the juggling of characters, costume pieces, and emotional levels seems to come as second nature. A few struggle as they try to master unfamiliar language and behavior.

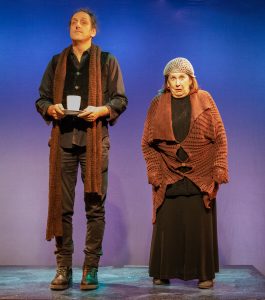

Richard Abraham has an angular, asymmetrical face that could have been drawn by Edward Gorey. He is great fun as the husband who dreams of poisoning or otherwise killing his harridan of a wife, played with acidic, vinegary perfection by Carol Kline. Jennifer Kenyon does a sly, spirited turn as the woman who keeps a firm hold on her germ-free home (“Before you let the sun in, mind it wipes its shoes!”) and an even firmer hold on her two late husbands. Katherine Griffith is physically and vocally agile, able to shift characters on a dime, and she has her sweetest moments as a joyful old woman who happily greets each day reciting the years, months, and days she has been alive.

Other standouts include Jade Santana and Bryan Bertone, with at least seven roles between them. Bertone’s first scene dreaming about his “little piggies” is a delight, and Santana is a force of nature when she plays a girl demanding pennies or kisses from boys. If any character can be said to be the emotional heart of the play, it would be Polly Garter, a free spirit with children from many different lovers whose one true love is dead. Gina Manziello is warm and passionate as Polly. She provides a sort of ballast, as her depth allows other characters to take fanciful flight without fear of floating away. And she sings beautifully.

The first of many wise decisions director Ben Martin makes is to forego the Welsh accent. One would be hard pressed to find eighteen actors anywhere outside of Wales who could get it right, and more importantly, get them to sound as if they come from the same village. I doubt Martin is all that interested in the idea anyway. He also avoids going too over-the-top with the villagers’ “lusty bawdiness.” A little of that sort of thing goes a long way, and can come across as sophomoric, like seventh-grade boys saying the word “penis” and then giggling uproariously. Sex in Llareggub is matter-of-fact, something to censure for some, avoid for others, and enjoy for most. In modern parlance, it is what it is. No need for coy winks or other embellishments.

The staging is impeccable. Martin creates beautiful tableaux and keeps the energy flowing, while expertly establishing the different households and lives of the villagers. We are never lost or confused. Perhaps the true heroes of the evening are Bruce Dickinson and Ina Shumaker, whose props are often the only visual clues we have to the many changes of character and location, along with clever changes in accessories from costume designer Carol Brolaski Kline. Their work is splendid, as are what I imagine to be the herculean labors of stage manager Jennifer Palumbo — this is not an easy show to call.

photos by Darrett Sanders

Under Milk Wood

Under Milk Wood

Open Fist Theatre Company

Atwater Village Theatre

3269 Casitas Ave. in Atwater Village

Thurs-Sat at 8; Sun at 7

ends on August 25, 2018

for tickets, call 323.882.6912

or visit Open Fist