UNMASKING A GAY HERO

There is a method of political activism called a “zap.” Basically, zaps are militant but non-violent face-to-face confrontations with persons in positions of authority, but when used in tandem with a media alert, they can be powerful weapons when furthering a cause. Since gay activists in the late 1960s and early ’˜70s represented a  largely closeted community, they didn’t have the manpower for mass demonstrations, such as the 1971 May Day antiwar demonstration in Washington D.C., so zaps were one of the few effective tools at their disposal.

largely closeted community, they didn’t have the manpower for mass demonstrations, such as the 1971 May Day antiwar demonstration in Washington D.C., so zaps were one of the few effective tools at their disposal.

It just so happens that amidst those May Day Protests — while the Nixon Administration sent 10,000 troops to tear gas and arrest Vietnam War protesters — the American Psychiatric Association (APA) was holding its annual conference in the chaotic city. Separate from the tiny “Gay Mayday” contingent of the protests was the newly formed D.C. chapter of Gay Activists Alliance, whose planned zap allowed Frank Kameny, one of the most noteworthy figures in gay rights history — and who coined the phrase “Gay is Good” — to sneak into the conference, seize a microphone, and protest the diagnosis of homosexuality as a mental illness. As a result, gay advocates were invited to a panel with psychiatrists at their next convention.

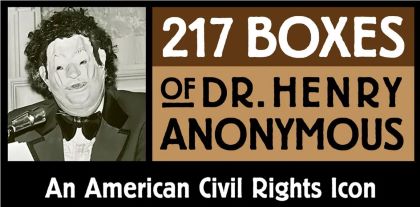

It was there in Dallas, 1972, that John E. Fryer, a gay psychiatrist, appeared using a wig, mask, and voice-distorting microphone to shield his identity. Sitting alongside Kameny and fellow-activist Barbara Gittings, Fryer was introduced as “Dr. H. [for homosexual] Anonymous” at a panel discussion titled “Psychiatry: Friend or Foe to Homosexuals: A Dialogue.” This appearance helped to galvanize a group of largely closeted gay psychiatrists within APA at a time when homosexuality was still widely viewed as pathological by both psychiatrists and society-at-large. The following year, APA removed homosexuality from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

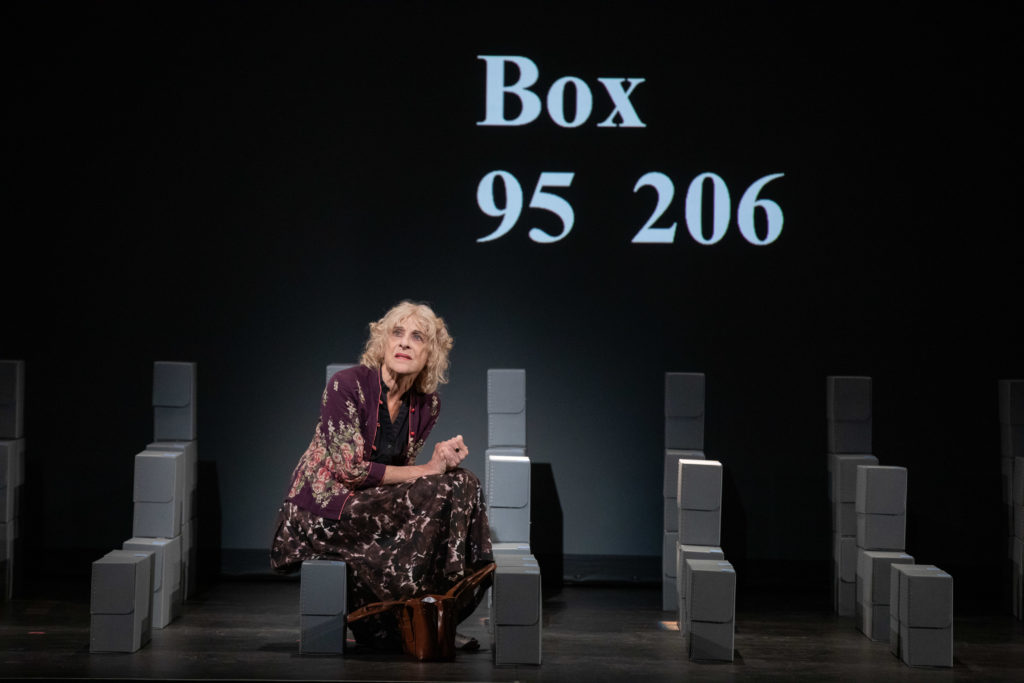

You won’t meet Dr. Fryer in Ain Gordon’s fascinating work, 217 Boxes of Dr. Henry Anonymous, which ran last weekend at UCLA’s Freud Playhouse, but you meet three people who elucidate not just the life and times of this closeted individual but the eras before and after his famous speech. Courtesy of UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance, information is scattered throughout the lobby and in the courtyard regarding the gay movement and its current state. It’s all crucial but it’s also a lot to take in. In a way, so is 217 Boxes which started to feel a bit long even at 70 minutes. But that’s the nature of this admirable beast.

After Fryer’s death in 2003, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania commissioned Mr. Gordon to examine the psychiatrist’s archive — 217 boxes of Fryer’s papers. Culling from correspondence, newspaper clippings, postcards, travel diaries, photographs, subject files, patient records, Fryer’s own medical files, and more, Gordon developed three characters, each with a 25-minute monologue.

The first, played by Derek Lucci in a riveting performance, is Alfred A. Gross, a self-defining “high swish” born in 1895, who addresses us as “Dear Ones.” Gross brought patients to Fryer in the ’60s — men who were arrested for sexual misconduct; if they were treated then those horrible charges could be dropped. Thus, the damaging effects of living in the closet were brought into Fryer’s office. The dialogue is highly theatrical yet halting and interruptive, sometimes cleverly and skillfully evasive, as if Gross is indeed making the dialogue up on the spot. While this style worked perfectly for the first monologue, that abstract nature made the second seem a bit drawn-out.

Fired from her long-time job because of her age, Katherine M. Luder became Fryer’s secretary after his famous speech. She stayed with him for 24 years until her death at 91, and their relationship mirrored that of a marriage — the good and the bad (“Exhausting — these men,” she says). Laura Esterman’s delivery as Luder is not far from an eccentric school marm; it seems more lecture than personal until — through her accounts of patients — we get a startling clear picture of both the liberation movement and the AIDS epidemic.

Understand that all three characters are speaking from the grave, as it were. When Dr. Fryer’s father, Ercel (the patient and understanding Ken Marks), reads as part of his monologue the famous speech, we already know that he died before it was delivered. The speech itself is quite simply remarkable, for it speaks to the underlying cause of homophobia which leads to the distress of the homosexual. Father and son exchanged letters, so we get a sense of the difficulty Ercel had in even conceptualizing homosexuality. He leaves us with a gentle call-to-arms to pick up the baton in the race for rights.

As always in theater, we need conflict, so this subject matter would be have been far more compelling in dialogue; you may leave wanting to know much, much more about Fryer (which may well be Mr. Gordon’s agenda). Still, the writer/director paints an accurate, historically detailed, funny, tragic and occasionally moving picture of life for the gay community in the twentieth century — a march for acceptance which is still far from being achieved around the globe.

photos by Reed Hutchinson and CAP UCLA

draft of John Fryer’s speech from Historical Society of Pennsylvania

217 Boxes of Dr. Henry Anonymous

Pick Up Performance Company(s) Production

UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance

Freud Playhouse, UCLA

played October 20 & 21, 2019

for future events, visit CAP UCLA

for more info, visit 217 Boxes