BAD COP GOOD COP

The cynical title My Kind of Town acknowledges the pop song that celebrates Chicago but also a likely culture of police brutality. This is the work of investigative journalist John Conroy, who wrote 22 articles on police torture in Chicago from 1990 to 2007. Conroy may not be an experienced professional playwright, but in My Kind of Town he’s written a complex, human, and disturbing drama that can unnerve the spectator with its ambiguity. Audiences at the TimeLine Theatre expecting a no-brainer indictment of Chicago police torture are in for a surprising, unsettling, and suspenseful evening. What could be a black-and-white exposure of police brutality turns out to have a disturbing amount of gray in its mix.

Conroy’s play is a fictionalized version of the scandal that emerged from newspaper and government investigations from the 1980’s to the present. The story centers on a police detective named Dan Breen and his colleagues and what they did to arrested men in the basement of Area 2 headquarters that resulted in a confession rate approaching 100%.

One of those confessions was extracted from Otha Jeffries, a violent and hostile young black thug accused of murder. Jeffries sits on death row after being convicted of murder based on a confession he insists was given under torture. Otha’s mother is on a crusade to exonerate her son. Ironically, his father is a police officer who stands aloof from Otha’s violent and anti-social behavior.

The play also brings in a female state’s attorney, a black former police detective (who may have knowledge of the brutality), a lawyer working pro bono to exonerate Otha, and Breen’s wife and sister-in-law. In a series of scenes that shift back and forth in time, we see the stresses that the brutality scandal inflicts on the characters. There are the domestic strains tearing apart the Jeffries family and the tensions between Breen and his wife, who wants to believe her husband is clean, but can’t help but wonder. Enormous pressure is put on the black former detective and the state’s attorney to close ranks with their police brethren against charges from outsiders that could ruin careers and personal lives. Loyalties are tested, lies are told, and memories are conveniently vague.

The implication throughout the play is that the torture charges are legitimate, but that invites the uncomfortable matter of the ends justifying the means. Breen, who never admits any wrongdoing, proudly claims that he and his colleagues are the first and last line of defense against the killers and rapists that infect the city. If the police don’t protect citizens against criminal depredations, who will? It’s a statement that will resonate with members of the audience, even those who consider themselves of a liberal persuasion, when they confront the specter of lawlessness and violence that may be just down the street, with only the police standing in the way of mayhem.

The implication throughout the play is that the torture charges are legitimate, but that invites the uncomfortable matter of the ends justifying the means. Breen, who never admits any wrongdoing, proudly claims that he and his colleagues are the first and last line of defense against the killers and rapists that infect the city. If the police don’t protect citizens against criminal depredations, who will? It’s a statement that will resonate with members of the audience, even those who consider themselves of a liberal persuasion, when they confront the specter of lawlessness and violence that may be just down the street, with only the police standing in the way of mayhem.

And it’s not that the police are pictured as cold-blooded bad guys. Breen is a decorated veteran and a policeman flooded with citations of merit, and is active in charity work. If he is guilty, it’s not out of a love of power but a dedication to keeping the city streets safe from vicious criminals like Otha Jeffries.

The second half of the play turns into an engrossing courtroom-type drama as Otha’s lawyer and the young man’s parents struggle to secure Otha a hearing that could get him off death row. Who will testify truthfully and who will lie to save their reputations and to keep the faith with the policemen under fire? If telling the truth means releasing Otha Jeffries onto the Chicago streets to continue his life of violence, maybe the truth isn’t so attractive an option. The play sets up an ethical and moral dilemma for key characters that nobody in the audience would care to face.

The play does not end in neat resolution or closure. Real life does not resolve issues presented in My Kind of Town in a tidy and satisfying package. The spectators leave the theater awash in perplexity. It all should be cut-and-dried but instead “My Kind of Town” raises issues that leave the thoughtful spectator’s mind churning with unease.

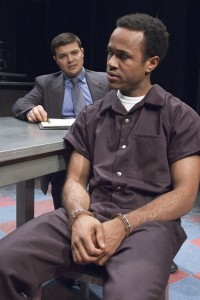

The TimeLine ensemble is filled with pinpoint casting. As the eye of the storm, Charles Gardner delivers a chilling and persuasive performance as Otha Jeffries, a man so twisted by society and his own demons that he is a menace to his family and to society at large. It’s a scorching and uncompromising piece of acting that doesn’t let the viewers off easy in ordering their sympathies. Ora Jones is brilliant as Otha’s anguished mother, desperate to clear her son of the murder charge while recognizing that liberating him from prison could release a destructive force too far gone in anger and hostility for redemption.

David Parkes gives us multiple, and conflicting, sides of Dan Breen. The audience will have no trouble accepting Breen as a sinister force within the police department, intimidating and brutal. And yet he’s a good family man, an ornament to the community, and devoted to forming a barrier between the violence of the streets and law-abiding citizens. It’s hard to admire the character but it’s just as hard to reject his dedication.

The rest of the cast falls in line with the excellence of the principals’”A. C. Smith as the black detective, Derek Garza as Otha’s lawyer, Danica Monroe as Breen’s wife, Carolyn Hoerdemann as his sister-in-law, Maggie Kettering as the state’s attorney, and Trinity Murdock as Otha’s father. The ensemble is beautifully orchestrated by director Nick Bowling, who lays out all the tangled emotions of the story with power and realism.

The production is performed at a brisk pace that reinforces the intensity of the story. Brian Sidney Bembridge designed the effective multi-level set for the intimate theater space. Alex Wren Meadows designed the costumes, Nic Jones the lighting, Mike Tutaj the video, and Mikhail Fiksel the sound (and composed the original music).

For the record, dozens of men have been released from Illinois prisons because their confessions were extracted under torture and the city of Chicago has paid out tens of millions of dollars in compensation to victims of police brutality.

photos by Lara Goetsch

My Kind of Town

TimeLine Theatre in Chicago

ends on July 29, 2012

for tickets, call 773 281 8463 or visit TimeLine

for more shows, visit Theatre in Chicago