I GET THE PICTURE

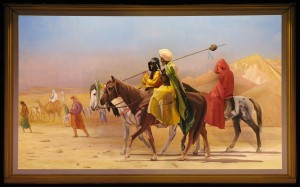

Pageant of the Masters’ The Big Picture is perhaps the most three-dimensional idea from the fertile mind of director Diane Challis Davy. Continuing the 80-year tradition of celebrating art with a performance of “living pictures”’”tableaux vivants’”this year’s production is a tribute to the history of motion pictures and the ways in which masterpieces of art have inspired and informed the movies. Every  year has its own theme, such as Eat, Drink and be Merry and The Genius, but this year allowed Davy to bring to life the widest-ranging array of art I have ever seen at the Pageant: film effects (including beginning and end credits); timeless works by Michelangelo (a tie-in to The Agony and the Ecstasy); Carlo Freter’s sculptures of Venus and Diana which adorn the Roman Pool at Hearst Castle (a tie-in to Citizen Kane); four Gainsborough portraits (a tie-in to Barry Lyndon); paintings by Vermeer (styles) and Jean-Léon Gérôme (dramatic spectacle); posters; lobby cards; and famous fountains used in cinema, including Roman Holiday’s Trevi (the shimmering water effects showcased the inventiveness of technical director/lighting designer Richard Hill).

year has its own theme, such as Eat, Drink and be Merry and The Genius, but this year allowed Davy to bring to life the widest-ranging array of art I have ever seen at the Pageant: film effects (including beginning and end credits); timeless works by Michelangelo (a tie-in to The Agony and the Ecstasy); Carlo Freter’s sculptures of Venus and Diana which adorn the Roman Pool at Hearst Castle (a tie-in to Citizen Kane); four Gainsborough portraits (a tie-in to Barry Lyndon); paintings by Vermeer (styles) and Jean-Léon Gérôme (dramatic spectacle); posters; lobby cards; and famous fountains used in cinema, including Roman Holiday’s Trevi (the shimmering water effects showcased the inventiveness of technical director/lighting designer Richard Hill).

With over 45 individual works of the utmost quality, professionalism and magnificence, it’s best to concentrate on but a few. It’s amazing that a viewing of so many wondrous creations doesn’t bring on Stendhal syndrome, a psychosomatic  disorder (dizziness, fainting, confusion) caused by looking at too much beautiful art.

disorder (dizziness, fainting, confusion) caused by looking at too much beautiful art.

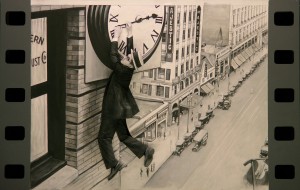

The movie stills of Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd were cleverly bordered by sprocket holes, and the actors in these scenes were wisely given the opportunity to move after holding their pose. The most ingenious film stills were Vertigo, which has Kim Novak gazing at art in a museum, and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, a segment used to honor Chicago’s Art Institute and highlight impressionist masters Seurat and Caillebotte.

As a tribute to Bette Davis, who volunteered for the Pageant in 1957 but had to cancel at the last minute (ah, Hollywood!), Davy chose Joshua Reynolds’ Sarah Siddons as the Tragic Muse. The consummate Dan Duling’s literate commentary, richly delivered by Richard Doyle, consistently offered nuggets of trivia. In this case, we learned that the portrait was used as the template for the fictitious Sarah Siddons  award in All About Eve. I discovered later that this invention of Joseph L. Mankiewicz became a reality just two years thereafter when some distinguished Chicago theater-goers re-invented it as an award for outstanding actors on the Chicago stage (well, celebrities as much as actors).

award in All About Eve. I discovered later that this invention of Joseph L. Mankiewicz became a reality just two years thereafter when some distinguished Chicago theater-goers re-invented it as an award for outstanding actors on the Chicago stage (well, celebrities as much as actors).

For those unfamiliar with the Pageant, lavish sets, painted with painstaking precision, provide the backdrop for its hundreds of volunteer cast members wearing elaborate costumes, stiff hats and wigs, and perfectly shaded make-up. The result: stunning artwork re-creations on the grandest scale. So seamless is the display that it’s nearly impossible to tell where the background painting stops and the costumes start’”or which figures are painted into the set and which are represented by actors posing within the artwork. Set, costumes, lighting, and music all come together in a spectacular display that’s a true feast for the senses.

Every year without fail, one of the highlights is a glimpse into the making of these living works. This year, the sold out crowd collectively held its breath for Frederic Remington’s A Dash for the Timber, which currently hangs in the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. The 1889 oil painting, which portrays cowboys in the Southwest shooting at Apaches behind them, is revolutionary for illustrating  airborne horses in true gait. Remington was influenced by Eadweard Muybridge, whose fast-action sequential photographs were displayed by the Pageant in black-and-white glory immediately following A Dash for the Timber.

airborne horses in true gait. Remington was influenced by Eadweard Muybridge, whose fast-action sequential photographs were displayed by the Pageant in black-and-white glory immediately following A Dash for the Timber.

In dim light, the background set’”inside a giant shadow box’”rolled onto the playing area facing upstage. With their backs to us, costumed cast members assumed their stance. An arm stretched this way, a head turned that way, a knee bent. After the “wagon” rotates 180 degrees, a massive frame was adjusted to fit the “canvas.” But as the stage lights came up, the magic transpired: Individual elements, silent and motionless, ceased to exist as they melted into the background and transformed the scene into a living work of art.

The ripple of sensations which occurs within the next 90 seconds is mind-blowing. First is the shock of the work itself. Remington had accompanied General Cook on the trail of Geronimo, so he knew firsthand what a hostile Indian encounter was like. With fine alkali dust swirling about the hot, barren landscape, the eight cavalrymen, one of them wounded, exude exhaustion, panic, and adrenaline as a  cluster of Apaches approaches threateningly in the background. There is almost a sense of vertigo as the figures seem to be moving, yet the actors remain perfectly still. Then, your eye scans the image, looking at details: the cornflower-blue shadows; a chestnut horse gasping for breath as foam pours from its mouth; the scarves and reins flapping in the wind. Then the uncanny feeling when you notice that one of the riders and another horse are looking directly at you with palpable desperation, but there is nothing you can do to assist their fearful flight. Then you scrunch your attention on the faces, some in vivid detail, others obscured by the dust or the shadow of a hat. The ferocious action of the scene forces you back, but the meticulous details keep pulling you in.

cluster of Apaches approaches threateningly in the background. There is almost a sense of vertigo as the figures seem to be moving, yet the actors remain perfectly still. Then, your eye scans the image, looking at details: the cornflower-blue shadows; a chestnut horse gasping for breath as foam pours from its mouth; the scarves and reins flapping in the wind. Then the uncanny feeling when you notice that one of the riders and another horse are looking directly at you with palpable desperation, but there is nothing you can do to assist their fearful flight. Then you scrunch your attention on the faces, some in vivid detail, others obscured by the dust or the shadow of a hat. The ferocious action of the scene forces you back, but the meticulous details keep pulling you in.

Adding to the emotional experience is the 28-member orchestra under the sterling leadership of John Elg. While the evening included more previously published music than usual, Victor A Vanacore’s original “A Dash for the Timber” evoked  classic western film scores, perfectly emulating the likes of Jerome Moross (The Big Country) and Elmer Bernstein (The Magnificent Seven). Even familiar scores had new life breathed into them with exciting arrangements. Kim Schamberg avoided syrupy Muzak for his arrangement of “Gigi” to accompany Carpeaux’ fountain Les Quatre Parties de Monde, instead offering a lush, romantic rendition of the Lerner & Loewe tune. Alan Steinberger and the husband-and-wife team of Starr Parodi & Jeff Eden Fair also contributed original compositions and arrangements.

classic western film scores, perfectly emulating the likes of Jerome Moross (The Big Country) and Elmer Bernstein (The Magnificent Seven). Even familiar scores had new life breathed into them with exciting arrangements. Kim Schamberg avoided syrupy Muzak for his arrangement of “Gigi” to accompany Carpeaux’ fountain Les Quatre Parties de Monde, instead offering a lush, romantic rendition of the Lerner & Loewe tune. Alan Steinberger and the husband-and-wife team of Starr Parodi & Jeff Eden Fair also contributed original compositions and arrangements.

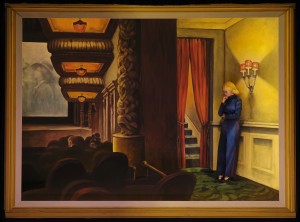

Bill Liston composed original music for the final sequence of Act I, recreating the sounds of Hollywood’s golden age, but also arranged and orchestrated in rousing fashion the familiar songs, “You Oughta Be in Pictures” and “You Stepped Out of a  Dream.” And it is this sequence which displayed the most and least successful elements of the evening, beginning with Edward Hopper’s 1939 New York Movie, which has a deep-in-thought usherette standing beneath a wall light aside a palatial, darkened auditorium. The onstage re-creation actually heightened that Hopperesque world of loneliness, isolation and quiet anguish. Since The Big Picture validates how film-makers have looked to graphic artists for inspiration, it should be mentioned that the voyeurism, moody highlights, and enigmatic familiarity of Hopper’s work heavily influenced film noir.

Dream.” And it is this sequence which displayed the most and least successful elements of the evening, beginning with Edward Hopper’s 1939 New York Movie, which has a deep-in-thought usherette standing beneath a wall light aside a palatial, darkened auditorium. The onstage re-creation actually heightened that Hopperesque world of loneliness, isolation and quiet anguish. Since The Big Picture validates how film-makers have looked to graphic artists for inspiration, it should be mentioned that the voyeurism, moody highlights, and enigmatic familiarity of Hopper’s work heavily influenced film noir.

Norman Rockwell’s Saturday Evening Post cover of Hollywood Starlet came next. The cast was frozen flawlessness as they portrayed the paparazzi of 1936 surrounding a platinum blonde freshly arrived in Hollywood. After scanning the  figurative work about one minute, an audience member whispered, “Look at her face. My God, it’s just perfection.”

figurative work about one minute, an audience member whispered, “Look at her face. My God, it’s just perfection.”

Even more thrilling was Thomas Hart Benton’s 1937 Hollywood, a cynical look at the film world. Commissioned as a two-page spread by Life magazine, this masterwork features a scantily clad blonde on a film set which represents Hollywood’”in typical Bentonesque fashion’”as a muscular industry (Life subsequently refused to run it because of the half-naked woman in the center). With figures both darkened and lit permeating the landscape, this breathtaking re-creation was massive in scope and had many stories going on at once. Being reminded of how many people it takes to make a film, Hollywood triggered in me the thought of how many people contributed their efforts to have this night happen.

After that staggering piece, the display of six Erté statues and a serigraph (Queen of the Night, which graces this year’s poster), felt like a letdown. Yes, the art deco designer worked on sets and costumes in Hollywood, but these works from the  Russian’s later years, however stunning, just didn’t seem to fit the bill (kudos to Davy, however, for displaying them on a Busby Berkeley-type staircase situated on a turntable’”that alone got applause.) After the Ertés, a roar of oohs and aahs came from the audience down left. We could barely catch a glimpse of a classic cream-colored car, out of which came a Jean Harlow-esque star to accept an award that mimicked the Oscar (ain’t no way the

Russian’s later years, however stunning, just didn’t seem to fit the bill (kudos to Davy, however, for displaying them on a Busby Berkeley-type staircase situated on a turntable’”that alone got applause.) After the Ertés, a roar of oohs and aahs came from the audience down left. We could barely catch a glimpse of a classic cream-colored car, out of which came a Jean Harlow-esque star to accept an award that mimicked the Oscar (ain’t no way the  Academy will allow their statue to be reproduced). While the show picked up steam again in Act II, it had trouble recovering from the anticlimactic first act finale.

Academy will allow their statue to be reproduced). While the show picked up steam again in Act II, it had trouble recovering from the anticlimactic first act finale.

Still, this is currently the greatest show around, and I am happy to report the inclusion of Rick Terry’s Storytellers, a bronze of Walt Disney and his Mouse that resides in nearby Disney’s California Adventure. Disney was a visionary and a treasure to the the arts community in general. So, too, is The Pageant of the Masters. Their shows inspire me to learn more about art and celebrate its existence.

The Big Picture

The Big Picture

Pageant of the Masters

Irvine Bowl, 650 Laguna Canyon Road

Laguna Beach

part of The Festival of the Arts

scheduled to end on August 31, 2013

staged nightly at 8:30

for tickets, call 800.487.3378

or visit http://www.PageantTickets.com