THE STURDIEST DILAPIDATED HOUSE IN TOWN

When she enters her house, so badly in need of repair that it might as well be razed as restored, she walks with a strange somnambulistic slowness, one foot seeming to go forward and the other simultaneously taking a step backward. She doesn’t seem to mind being drenched, as her husband does, and indeed seems impervious to the howling winds and lashing rains beating against her door and leaking into her living room. The sounds of orgiastic pleasure, coming from the floor above, don’t seem to concern her, either. Signs of life are, after all, signs of life. She has hardly had time to remove the stink of death that has invaded her weary bones, having just returned to Passagoula, Mississippi from a weekend in Memphis where she buried her gay son Chips, the most beloved of her three children. Grief seems to be clouding her memory, but it could just as easily be terminal boredom or the recognition that her own death is drawing near.

She is Bella McCorkle, the woman at the heart of A House Not Meant To Stand, the last play of Tennessee Williams. And she is brought to scarily brilliant life by Sandy Martin in a career-transforming performance that doesn’t miss a beat of the text, going from one extreme to another – from the comic to the tragic, from standing still to falling down, from the outrageous to the muted – in as slippery and cockeyed a fashion as Williams must have intended. And when Ms. Martin sits alone on the broken-down couch of her crumbling house, stuffing pills down her throat, one after another, unsure whether or not she has already taken one just a second before, she suddenly gets lost in reverie, and the image is so palpable that we almost don’t need the spectral image of her dead son to know what she is thinking. And yet, it is one of the most extraordinarily hallucinogenic images in a production that takes inordinate pleasure in fantastical imagery. But it is Ms. Martin’s stillness that breaks one’s heart. In that moment, it is as if the character of Amanda Wingfield, based on the playwright’s mother, has been transformed into this dissolute creature named Bella McCorkle who resembles, to a great degree, Tennessee Williams himself. And it brings to full circle the arc from The Glass Menagerie to A House Not Meant To Stand.

She is Bella McCorkle, the woman at the heart of A House Not Meant To Stand, the last play of Tennessee Williams. And she is brought to scarily brilliant life by Sandy Martin in a career-transforming performance that doesn’t miss a beat of the text, going from one extreme to another – from the comic to the tragic, from standing still to falling down, from the outrageous to the muted – in as slippery and cockeyed a fashion as Williams must have intended. And when Ms. Martin sits alone on the broken-down couch of her crumbling house, stuffing pills down her throat, one after another, unsure whether or not she has already taken one just a second before, she suddenly gets lost in reverie, and the image is so palpable that we almost don’t need the spectral image of her dead son to know what she is thinking. And yet, it is one of the most extraordinarily hallucinogenic images in a production that takes inordinate pleasure in fantastical imagery. But it is Ms. Martin’s stillness that breaks one’s heart. In that moment, it is as if the character of Amanda Wingfield, based on the playwright’s mother, has been transformed into this dissolute creature named Bella McCorkle who resembles, to a great degree, Tennessee Williams himself. And it brings to full circle the arc from The Glass Menagerie to A House Not Meant To Stand.

There was a certain comic absurdity to the tragic untimely death of Williams – he choked swallowing the lid of a prescription vial in an attempt to get to his pills faster – that has not escaped the notice of Simon Levy, who directs the play with a sure grasp of its mutable nature. In addition to the lingering portrait of Bella stuffing those pills down, there is a wild moment, when another of the play’s characters drops his vial of nitroglycerine tablets and starts scrounging around for those that fell out in his mad rush to get to them, that goes directly to the craziness that the play embodies but which must have also been living inside Williams when he wrote it. And it is that craziness that makes House burst with so much life.

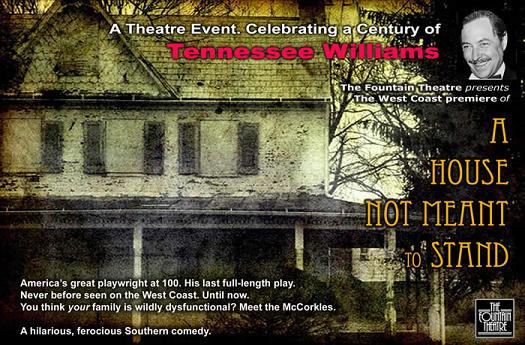

And what better way to celebrate the Williams centennial is there than to resurrect a play that is largely unknown and that, despite the fact that Time Magazine called it his best play in a decade when it was performed at Chicago’s Goodman Theatre in 1982, has rarely been produced in his own country? It is becoming increasingly clear that his late plays, which were reviled and dismissed when they were originally produced, are better now than they seemed then, although too many of them have yet to receive a definitive production. House may or not come to be counted among his genuine masterpieces, but Levy has at least given us a chance to see how fecund and bountiful his talents continued to be right up to the end. He was still experimenting with structure and content; he could still create characters, with all his art at his command, who matter; he was still capable of writing those insanely beautiful arias that any actor, rising to the occasion, can take pleasure in singing.

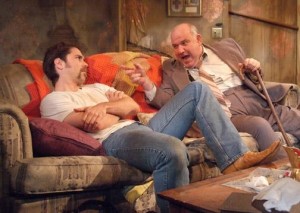

In the demented world of Bella and Cornelius McCorkle, the house they live in is a metaphor for the society they live in, as well as a metaphor for their own thwarted dreams. Williams called it “a gothic spook sonata” (referring, of course, to August Strindberg’s The Ghost Sonata, though Williams jokingly wondered what Strindberg would have thought of it) and it is indeed peopled by ghosts, but the real thrust of the work resides in how fully developed the living characters are, some drawn with sharpness, some with vivid brush strokes. There is a plot of sorts – about an inheritance that Bella may have received from the Dancies (her side of the family) and how Cornelius would like to get his hands on it to resurrect his failed political career – and there’s a curious set of folks who traipse through their house despite the fact that it is storming outside and it is well after midnight. There is the roustabout son who is constantly mistaken by Bella for her dead son and who has come home with a pregnant born-again Christian fiancée. There is a gun-toting and sex-hungry neighbor and his wife who has a penchant for the virtues of cosmetic surgery and the promise of the vices of younger men. They are all in this wacky danse macabre together, though their looniness often keeps them separate from each other. Indeed, Williams understood that most of us are like that: lonely and desperate and alone and probably mad and yet always reaching out for someone or something. And when they can no longer connect to each other, they reach out, in this play, to the audience. And Levy almost has them threatening to jump out of their skins and into the laps of the audience at the Fountain Theatre.

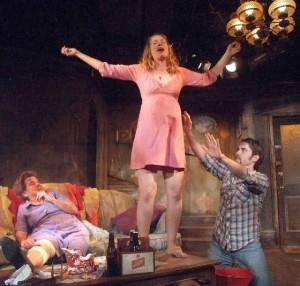

It is, as befits a Williams play, the women in the cast who strike the perfect balance between behavior that is recognizable and behavior that might be considered grotesque. Lisa Richards makes of Jessie Sykes, the lady of the multiple face lifts, a woman marooned on an island of regret and longing, and does it by being simultaneously hilarious and almost tragically moving. Virginia Newcomb’s born-again Christian, when in the throes of being moved by the spirits, has what must certainly be the funniest scene available to theater-goers at the moment. When the men – who are good and will no doubt get better as the play settles into its run – mine the comic possibilities of their roles, particularly in the first act, this could be the ensemble of the season.

Levy is aided and abetted by an exceptional design team. Jeff McLaughlin’s set is a masterpiece of decrepitude; it seems to deteriorate before one’s eyes, and the flimsiness of the wall separating the dining room from the living room develops a certain poignancy as the evening progresses. Keith Skretch’s video projections of  Bella’s ghosts are expressively haunting. And both Ken Booth’s lighting and Peter Bayne’s sound are so right that the audience, upon leaving the theater, may feel as if they are about to walk into a rainstorm of monumental proportions.

Bella’s ghosts are expressively haunting. And both Ken Booth’s lighting and Peter Bayne’s sound are so right that the audience, upon leaving the theater, may feel as if they are about to walk into a rainstorm of monumental proportions.

And Naila Aladdin-Sanders’s costumes are superb; the plastic raincoat over satin lingerie with which Ms. Richards enters in the second act captures perfectly the crazy-quilt feeling that the play exudes. If this reviewer has one serious objection to the stunning work on display, it is the suit that Ms. Aladdin-Sanders has put on Alan Blumenfeld (who plays Cornelius); it may be a cliché, but, as a failed Southern politician, it would probably work better if Cornelius were wearing a white linen suit, so begrimed with dirt that it is now gray, instead of the baggy brown suit that literally seems to be hampering Blumenfeld’s otherwise delightfully bellicose performance.

The discovery of A House Not Meant To Stand makes this not merely an important theater event, but a revelation of just how potent Tennesee Williams’s talent was in a period that has been categorized as one of decline. And Sandy Martin’s great performance does for Bella McCorkle what one imagines Laurette Taylor did for Amanda Wingfield. What she is doing doesn’t even look like acting. What higher compliment can one pay an actor?

photos by Ed Krieger

A House Not Meant to Stand

Fountain Theatre, 5060 Fountain Ave.

Thurs-Sat at 8; Sun at 2

ends on April 17, 2011 EXTENDED to May 22, 2011

for tickets, call 323.663.1525 or visit Fountain Theatre

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

Fascinating review! Here’s the latest from the Independent:

The problem with Tennessee: Too hot and too cool

A new exhibition reveals the American playwright’s battles to stage his plays in post-war London

By Guy Adams

Sunday, 13 March 2011

Tennessee Williams turned to post-war Britain to launch his career but ran into censorship problems because of his plays’ frankness about sex and homosexuality

He might have preferred to depend upon the kindness of strangers, but when Tennessee Williams attempted to launch his career in the West End theatres of post-war London, he met an altogether less friendly response: no sex, please, we’re British.

A collection of the American playwright’s private letters and documents being exhibited this month detail his extraordinary clashes with official censors who attempted to prevent both A Streetcar Named Desire and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof being staged in the UK.

They demonstrate how the Lord Chamberlain of the time, an Earl and former Tory MP in charge of licensing all new theatrical productions, took great exception to fruity language and blasphemy in the plays, which are today considered modern classics. His most furious moustache-twitching, the letters reveal, was prompted by references to homosexuality, which was illegal on both sides of the Atlantic. To the dismay of Williams, who was gay, he demanded that all but the most veiled references be cut.

A letter by the Lord Chamberlain to producers of the first London production of Streetcar reveals that eight changes were required, mostly to lines of the play’s volatile protagonist, Blanche DuBois. They included the deletion of the supposedly offensive word “rutting,” and a stern instruction that during the play: “there must be no suggestive business accompanying any undressing”. The censor further demanded that a famous scene in which DuBois recalls how she discovered her first husband in a romantic clinch with a gay lover should be reworked to leave the audience with the impression that the liaison had been heterosexual.

Streetcar was eventually staged, with Laurence Olivier as a director, in 1949, two years after it had opened on Broadway. But an effort to bring Cat on a Hot Tin Roof to the UK almost a decade later met even more severe difficulties. A 1955 letter from the Lord Chamberlain – part of a collection at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas – reveals that the producers were told to make 34 changes to the script before it was deemed acceptable for London.

Williams was told to delete allegedly offensive words, including “crap”, “Christ”, “Jesus”, “bull crap”, “frig”, “half ass”, “boobs”, “humping” and “ass-aching”. He was also told to cut a paragraph in which a character discusses a sexual liaison by saying: “I laid her, regular as a piston.”

More troublesome were instructions to remove entire pages that referred to the homosexuality of Brick, a prominent character. Phrases such as “ducking sissies” and “queers” had to be cut. A typical paragraph reads: “The discussion on page 45 [must] be altered, so as to eliminate the suggestion that there may have been a homosexual relationship.”

Since homosexuality is central to the play, Williams refused to make the changes. Letters between his producers and literary agent reveal how they decided to circumvent decency laws by turning the Comedy Theatre in London into a private members’ club. Directed by Peter Hall, the play opened controversially in 1958.

Cathy Henderson, who helped curate the Texas exhibition, says the arguments over homosexuality foreshadowed later rows with Hollywood censors, who were reluctant to endorse the 1950s film of Streetcar. “He [Williams] minded that his scripts were altered, but he did understand that he was pushing the envelope, and that sometimes compromises would have to be made,” she said.

Experts on post-war theatre say the prudish response was typical of the UK censor of the time. “The biggest arguments tended to revolve around plays coming to London from the US, since most British playwrights edited themselves,” says Sheffield University’s Dr Steve Nicholson, co-author of The Lord Chamberlain Regrets: A History of British Theatre Censorship. The Lord Chamberlain’s role as censor was abolished in 1968, allowing shows such as Hair to run in the West End. Many of his letters to producers are kept in the British Library, where they are occasionally mined by academics.

Sandy does make it look easy, doesn’t she? She’s a natural. You should have seen her in HS bio class. Even further back, her rendition of Gertrude Ederly in an elementary school show, rolling down the aisle of the auditorium on an AV cart, waving her arms in a wild freestyle stroke! She was so spontaneous and outrageously funny! I knew her when…and it seems she hasn’t changed a bit!