THE LONG TERM RELATIONSHIPS OF SINAN ÃœNEL AND LEO TOLSTOY

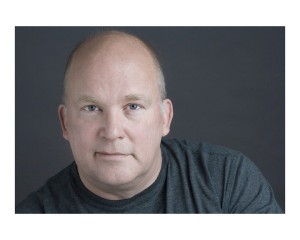

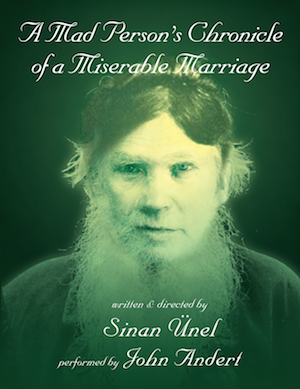

Cheryl King’s intimate Stage Left Studio on Manhattan’s West 30th Street specializes in showcasing one-to-two-person plays. Through November 22, Sinan Ãœnel’s A Mad Person’s Chronicle of a Miserable Marriage joins the eclectic repertoire of solo gems. Embodying both Leo Tolstoy and his wife, Sonya, John Andert stars in the play that was written especially for him. Sinan Ãœnel sat with Stage and Cinema’s Gregory Fletcher to discuss it.

John’s bio mentions that this is his seventh play of yours to perform.

Yes, it’s been a long, fruitful collaboration. Both on- and off-stage. Actually, this is the second time he’s performed this role. He originated it back in 1996 in Provincetown–more than originated, he collaborated with me as playwright and director.

Did working so closely add any stress to your relationship together?

No, we have a very easygoing time of it. He listens to my observations and I listen to his; it’s a very simpatico relationship.

How long have you been together?

Since 1982-83.

How ironic that a congenial long-term relationship takes on the turbulent, unhappy, long-term relationship of Leo and Sonya Tolstoy. Embodying both, John plays Sonya in Act I and Leo in Act II, chronicling their mad relationship for a modern day audience. When in their marriage do you think the rocky times began?

Most likely from day one, when he gave her his diaries to read. He had chronicled all his sexual conquests, including his serfs, prostitutes, and even friends of her mother’s. This was shocking to her. She didn’t know how to handle it. The promiscuity was shocking but also the fact that she’d been asked to read about it. It soon became clear that they disagreed about “how to live.” She had bargained to live the life of a Countess, surrounded by luxuries and privileges, while he wanted to live the much simpler life of peasants. She wanted their marriage to go in one direction and he in another.

What was your first contact with the Tolstoys?

I was reading Anna Karenina when I came across some of his biographies. His struggle with mortality and religion intrigued me as I was also wrestling with similar questions. Then I came across Sonya. Her volatile personality, her stubbornness, and her violent reaction to her husband’s philosophy interested me. She’s clearly a very strong character, and she and Leo together make quite a dramatic combination. Once he left the Orthodox Church and began to write religious tracts, their conflicts grew even more. He wrote a novel called Kreutzer Sonata, which put forward his highly antagonistic views about relationships between men and women. Clearly, he wasn’t a fan of marriage and blamed women. This book infuriated her and caused her a great deal of embarrassment. She was convinced that the book was directed against her and this put her over the edge. But, on the other hand, he didn’t believe in divorce either. Even if they were allowed to divorce, I don’t think they would have split in spite of all their problems, disagreements, and unhappiness. I think they were very much attached to each other, which is what my play is about: two people who can’t get away from each other although they are in so much conflict.

Does the title “Mad Person’s Chronicle” apply to both of them?

It really applies more to the actor who channels those characters in his mind. The madness of schizophrenia, the divided personalities, is embodied in the actor who comes onstage and lives through their lives.

It’s so theatrical and wonderful to see one actor play both roles. John embodies Sonya simply by putting on a dress, a pair of earrings, and a necklace cross. No wig, make up, or even shoes.

Originally, we tried a wig, but it was disaster. Then we realized, John wasn’t pretending to be Sonya, he was a male actor embodying her personality.

He starts and finishes as an actor. At the preshow, he’s onstage warming up his voice, his tongue, lips, getting ready for a performance. As he changes out of his street clothes, the transformation begins. It’s very theatrical and fun to watch.

This conceit of the actor changing clothes onstage in front of the audience led to the title, A Mad Person’s Chronicle of a Miserable Marriage .

Because the actor may be mad, playing two characters, who are in a mad marriage, and there’s also an unseen character–

The director, who has supposedly set up this stage for them and invited Leo and Sonya from a century ago to speak with a modern day audience.

A theater director or a madhouse director?

A theater director, who has arranged some of Leo’s and Sonya’s personal possessions, a pot of tea, for instance, and wants to make sure they’re comfortable.

And he runs the appropriate music and sound cues–

Yes, everything is properly arranged. Or not. Maybe they’re all mad. The play seems to say that we all suffer from this kind of divided personality.

In Leo’s dialogue in Act II, he wonders if modern medicine would have diagnosed Sonya with schizophrenia.

Yes, but I don’t think she’s schizophrenic, but obviously she’s very disturbed. Leo doesn’t know what schizophrenia is–it’s something he’s read about in the future time that he’s in. He knows Greek and therefore knows that the word schizophrenia means divided personality, so when he’s looking at us–the audience–he sees what we all embody and sees two sides of everything. He talks about the notion that we can go both ways and see both sides of issues, and he admires that we don’t regard this as a disability or a disturbing thing, but that it’s a part of us, that we are all, in a way, schizophrenic in modern times.

I’m guessing if Sonya were truly diagnosed by a doctor today, she would be considered manic-depressive.

Yes, probably. She has a lot of disappointments. She thought her marriage would give her a comfortable, affluent, prestigious life. When she first married Leo, he was a nobleman, a Count, with a big house, lots of wealth, and he turned out to be extremely talented–a genius. But after writing his two world famous books, War and Peace and Anna Karenina, he made a big shift, a psychological crisis. He went into a panic. From that moment on, he has a fear of death and a panic for understanding what life is about. Suddenly, he grew disappointed with Russian society, the upper class culture he was a part of, and he went the other way.

To the serfs, or as she refers to them, peasants.

Yes, once he made this shift, he lived among them, even as a nobleman. He grew to admire them, their simplicity and unpretentiousness, and he wanted to be one of them. Sonya rebelled.

And rightly so. Didn’t she have any children to side with her?

She had thirteen children. Not all of them survived. The play only mentions Sasha, who sided with her father. In the end, all the children were gone, and Sasha was the only one left in the house. Also, Leo grew very close to a man named Chertkov, who shared Leo’s religious philosophical views, and they spent a lot of time together. Before Chertkov, Sonya had been Leo’s partner in writing his great novels. She copied them time and again, working very hard on those great books. The family was collecting the royalties and living well. But then Leo decided to make his books available to the poor, very inexpensively, and Chertkov started taking over the business end of things. Sonya lost her power, her purpose, she felt isolated by Leo, betrayed by her daughter, Sasha, and jealous of Chertkov’s friendship with her husband.

I’m feeling a lot of compassion for Sonya. Is it just me?

There’s the dilemma. Plus, Tolstoy had all these religious followers who were living in his house. Chertkov called them Tolstoyans. Sonya was not amused; these religious followers were living off of them and never–as she complains–tipping the servants. She would have preferred Dostoyevsky to visit’”he would have tipped the servants!

Religious followers have never been big tippers. So were these Tolstoyans at the root of her problems with Leo?

And as I mentioned earlier–the diaries. They both kept copious diaries and shared them with each other, from day one. They wrote very personal things that you wouldn’t normally share with your spouse. The rule was that there would be “no secrets with each other.” The diaries and their contents became a huge arena of competition and conflict. In a way, the diaries became the way they fought and communicated with each other.

Maybe they meant it as a couple’s therapy, but instead it fueled the fire and made things worse.

Yes, it became very dysfunctional. She says that when he died, Chertkov edited Leo’s diaries and deleted anything Leo had to say about his wife in a positive light. His diaries today do feel less genuine and real than hers.

Another reason to be mad.

But then her anger gets the best of her, and she makes life hard for people who then want to get away from her. And in his final days, Leo does just that. But first, he writes her a letter and asks for her forgiveness. The question of forgiveness between these two is a big part of the play. She says at the beginning of the play that, although everybody thinks she’s guilty, she didn’t make him go and die. I think at the end, she also feels very responsible. She’s asking for his forgiveness and our understanding.

When he leaves the house that last time, he dies within days. Do you think he knew he was dying?

He says that he knew he was rushing toward his death. I think he wanted to live his last days in peace. He probably didn’t expect to die in a train station. He was eighty-two years old. When you see his photo, he looks ancient.

That last moment of his life was depicted in the 2009 film “The Last Station” with Christopher Plummer and Helen Mirren.

Yes, many people have written about them and their relationship, although I don’t know of another play. But I’m sure there’s one out there somewhere.

It’s a very poignant relationship, and with John’s performance, along with the writing that feels very rich, and Beethoven’s music that you’ve included–the end of the play is very haunting, and I didn’t want it to end. I wonder how the dynamics would change if a woman played both roles.

When I originally wrote it, John and I discussed the possibility of his sharing the role with our friend, the wonderful actor, Mary Neufeld. That never happened, and John made the role his own.

Perhaps someday in a long run of eight performances a week, it will be more appropriate to see a man and a woman in repertory.

Yes, it would be interesting.

Have you written about any other living people before?

I wrote a play about Tchaikovsky’s last days called Pathetique, named after the composer’s last symphony. The play also takes place ten years later, when his brother and nephew are still dealing with the rumors and their consequences. I read everything I could find. My love of research began with my play, Pera Palas. When I get involved with research, I feel like I’m really working. Research is a lot of fun, especially when you’re working on a period piece.

Is it obvious when you should stop researching and begin writing the play?

Yes, something grabs me, and I find the angle of the piece. With Tchaikovsky, I had to read for months before I figured out what the story was going to be. With this play, too.

Where do you store all that research?

In diaries–I keep two sets: a personal journal and a writing journal. And usually I keep a separate journal for each play.

Do you share your personal diaries with John?

Never. Look what it did for Leo and Sonya.

Just checking. What are you working on currently?

Well I don’t want to elaborate too much, but I’m researching an ongoing archeological excavation in Turkey. I’ve been researching for a long time but still don’t know what the play is yet.

Setting another play in your homeland, how exciting. Might you be our most famous Turkish American playwright?

John jokes and calls me “the greatest living Turkish American playwright.” I have a dual citizenship; my dad came here from Turkey to do his graduate work at the University of Michigan. My mother was there as an undergrad; she was from Oklahoma. After they graduated, they were married, and I was born in San Francisco, and then they moved to Turkey. I grew up there and then, like my father, came here for college. I went to the University of Kansas for my undergraduate degree, and then years later I earned an MFA in Playwriting from Boston University.

Great school–the Boston Playwrights’ Theatre is a gem for BU playwriting graduate students.

Yes, absolutely.

How often do you return to Turkey?

How often do you return to Turkey?

Every couple of years.

Have your plays been produced there?

No, can you believe it? It’s unnerving. Pera Palas is a love letter to Istanbul, and they haven’t gotten it together to produce it there.

Do they know you’ve been produced in Boston, London, New Haven, New York, Provincetown, Germany, Austria, even Pasadena?! Who should I call?

I wish I knew; it’s maddening.

Just as long as it’s not a Tolstoy madness.

A Mad Person’s Chronicle of a Miserable Marriage

Stage Left Studio

scheduled to end on November 22, 2011

for tickets, visit http://www.stageleftstudio.net/tour-ticket.php?id=4