MEMPHIS PROVIDES RHYTHM

BUT ULTIMATELY GIVES YOU THE BLUES

Kicking off its national tour, Memphis blew into Chicago trying to sell itself as a romping, stomping celebration of rhythm and blues and rock ’˜n’ roll during its turbulent early years in the 1950s. There is plenty of energy on the stage at the Cadillac Palace Theatre, especially from the dancers, but the show has a synthetic feeling to it. The book is predictable and the 19 songs, while they emulate the music of the 1950s, sound more like cover versions of the great anthems of the period.

Memphis centers on a young white male named Huey Calhoun, an illiterate doofus who falls in love with black music. Battling the racism of Memphis during the early 1950s, Calhoun rises from local disc jockey to concert promoter, a blend of Alan Freed and Dick Clark. Calhoun falls for a young black singer named Felicia Farrell, an interracial relationship that could be hazardous to their health back in the segregated postwar era in Memphis.

Memphis centers on a young white male named Huey Calhoun, an illiterate doofus who falls in love with black music. Battling the racism of Memphis during the early 1950s, Calhoun rises from local disc jockey to concert promoter, a blend of Alan Freed and Dick Clark. Calhoun falls for a young black singer named Felicia Farrell, an interracial relationship that could be hazardous to their health back in the segregated postwar era in Memphis.

Huey and Felicia ascend in their musical careers as their love interest gets tighter and tighter. Then, inevitably and predictably, they have a falling out. Huey wants to stay in Memphis – rejecting the possibility of a big career jump as a TV dance party host – and Felicia wants to move to New York City where recording offers await and she is free of the racial divide of the Deep South. So, finally, Huey goes his way and Felicia goes hers, but they have an onstage reconciliation at a Felicia concert to end the story on a warm and fuzzy, if rueful, note. The love affair between Huey and Felicia is difficult to accept, especially from Felicia’s side, but that’s how Joe DiPietro wrote the book so that’s what the audience is stuck with.

The familiar trajectory of the Huey-Felicia relationship isn’t the only cliché in the show: Huey’s mother starts off as a low class racist (“She ain’t nothin’ but a colored girl”), but by the second act she has seen the light of racial harmony, belting out a hip-swiveling gospel solo, “Change Don’t Come Easy,” as blatant an audience pandering number as I have ever heard.

Then there is Gator, a bartender at a small African American club in Memphis. Gator has been a mute since the age of five, when he was traumatized by watching his father being lynched, but when Gator breaks out of his silence in time to lead the first act finale in “Say a Prayer,” it is clearly intended to send the spectators into the lobby at intermission with a large lump in their collective throats.

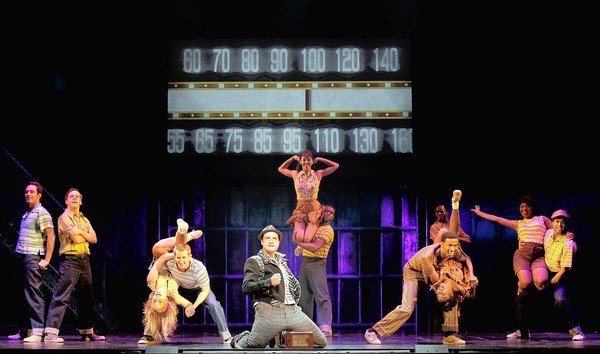

The character of Huey Calhoun may have been inspired by Dewey Philips, a white Memphis disc jockey who was a pioneer in playing black music for white listeners on the radio. Huey’s devotion to black music has saved him from being a loser all his life, so he rides his brashness, and a bit of good luck, into Memphis stardom as the city’s leading radio personality (goodbye Perry Como, hello Elvis Presley). Anyone in Chicago old enough to remember Dick Biondi knows the DJ type.

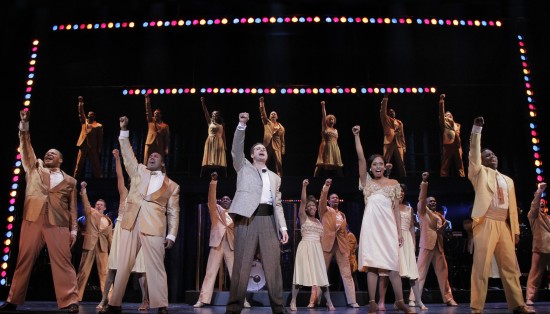

Bryan Fenkart, with a cornpone accent, acts well and sings and dances passably in a demanding role that puts him on stage for almost the entire show. Although Fenkart is locked into a cartoonish role, the opening night audience loved his “aw shucks” personality. Felicia Boswell displays a big voice as Felicia Farrell, and shows some welcome fire in ripping Huey for not going to New York City with her, and away from the racist miasma of Memphis; her verbal blast about life on the black side of the color line is the most honest moment in DiPietro’s book.

There are only a few supporting roles of consequence. As Mama, Julie Johnson is as persuasive as the writing allows, and she does milk her gospel number to considerable effect. Quentin Earl Darrington plays Felicia’s brother Delray and Will Mann plays Bobby, a black janitor at Huey’s radio station who turns out (surprise, surprise) to have great rhythm and blues singing chops. William Parry does a fine job as the white radio station owner who attaches himself to Huey and Felicia as they rise in the music world (he doesn’t sing or dance, but provides a welcome injection of realism into the wobbly narrative).

David Bryan (keyboard player of Bon Jovi) wrote the music and lyrics, which superficially recreate the sounds of R&B and first generation rock, but there is nothing original in the score and nothing the audience can take with it out of the theater, with the possible exception of the rousing “Everyone Wants to Be Black on Saturday Night.”

The biggest upside in Memphis resides in the chorus, full of exuberance and stamina as they jive through Serge Trujillo’s animated if not particularly original choreography. Director Christopher Ashley recreates his Broadway staging on David Gallo’s skimpy sets (Gallo shares the projection design credit with Shawn Sagady); the television simulcasts of the onstage dancing are the best technical effects in the show, made even more effective by Howell Hinkley’s lighting. Paul Tazewell designed the costumes, Ken Travis the sound and Alvin Hough, Jr. conducts the swinging offstage band.

Memphis puts the spectator in mind of Hairspray, another musical that dealt with the early years of rock ’˜n’ roll and racial conflict, except in 1960s Baltimore. But the Hairspray dance numbers soared far above anything in Memphis and the story was both funnier and more dramatic. Even though the audience at the Cadillac Palace did give the cast a standing ovation – a knee-jerk tradition now occurring in theaters around the country on opening nights – their applause sounded sincere. But anyone seeking authentic old-time rock ’˜n’ roll in Chicago is advised to check out Million Dollar Quartet, just a couple of miles north of the Loop.

photos by Paul Kolnik

Memphis

ends in Chicago on December 4, 2011

tour continues to August 12, 2012

for tickets, visit Broadway in Chicago

for more shows, visit Theatre in Chicago