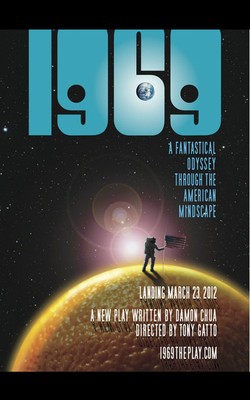

ONE VERY, VERY SMALL STEP FOR DAMON CHUA

Tony Gatto gets an A for effort, having mounted a colorful if unnecessarily literal production of a Damon Chua script that defies dramaturgy and good sense even as it embraces bad and even offensive conventions. 1969, billed as “a fantastical odyssey through the American mindscape,” feels more like a self-indulgent slog through a playwright’s inner monologue. Producers Fayna Sanchez, Chua and Gatto have corralled an impressive log of design talent and some committed, talented actors, in service of a play unlikely to be remembered as anybody’s best work.

1969 places, in unhistorical circumstances, several historical characters including American Atheists founder Madeline Murray O’Hair (Rebecca Avery) and her sons Jon (Ken Peterson) and Bill (Pat Scott); Apollo 11 astronaut Michael Collins (Brendan Farrell) and his son Junior (Rod Kellar); and the ghost of Mary Jo Kopechne (Meredith M. Sweeney), who in this story is not killed in the car wreck that does kill Ted Kennedy (Kyle Overstreet): instead Kopechne makes a deal with an anthropomorphic tree (Brett Fleisher), trading her life for Kennedy’s in an extreme fit of hero-worship. The ill-conceived character of Tree, a sort of sinister vegetable Koch brother, underwrites the work of Anita Bryant (Annie McCain Engman) in promoting both Florida orange juice and the Christian Right agenda, and sends Kopechne on an odyssey of evangelism she is told she must perform if she wants a happy afterlife. Thus she meets Bill O’Hair, a Vietnam veteran complete with violent flashbacks and a thousand-yard stare, whose psychoses include a belief that his real family (David Pavao and Chloe Peterson) lives in his television. Abandoning her guardian angelship of Bill, Kopechne travels to the moon with Junior in a stolen UFO to correct another major difference between this 1969 and the one that happened on earth.

Sounds like fun, right? Surely something could be made of all that. But this play isn’t a comedy; much of the subject matter is horrific in nature, and the most ridiculous elements are presented as deadly serious. Anyway, it’s not funny, with a single exception (a sci-fi movie glimpsed twice on late-night TV; if the whole show had been written, directed and acted in the style of those two brilliant scenes, it would be worth its weight in box office gold). The writing is flawed in every way: it invents rules for its universe to which it is casually unfaithful; it bores when it should thrill; it drops promising premises in favor of whimsical dead-ends.

The play’s many narrative threads are never tied or sewn or even left to hang but almost willfully unraveled by their weaver: Junior’s rescue mission, for one, jibes absolutely not at all with the convention, established elsewhere in the play, of revising alternate-reality history to match existing records outside the play. In an alarming lack of taste, Chua and Gatto present a pair of gay characters as such mincing, prancing stereotypes that I thought for a second I had gone back to the real1969. Least forgivably, much of the dialogue in this talky play simply fails to serve any purpose: it’s not amusing; it’s not clever; it doesn’t further the story; it just fills the many, many one- and two-minute scenes that litter the play’s problematic landscape.

One serious production problem, that might account for much, is the pacing; if Gatto can suck the air out of the leaden scenes and interminable scene changes, he could cut easily five and maybe ten minutes off the running time. When you’re directing a show full of short scenes, you must work the scene changes as heavily as the scenes themselves, and sometimes this means giving up a costume change; sometimes it means not allowing your designers to do all they can within the budget…

’¦ because another problem, causally related to the pacing issue but less easily fixed, is the decision to stage the show as realistically as possible, on a small-theater budget. The result is a tech-heavy show that has to scrimp here and there. For half a million bucks, you can build a giant television that characters can pop in and out of (really beautiful work by set designer David Mauer and video designer Adam Flemming) and still have money to build a spaceship (barely there at all), a car (not there), a forest (ditto). But if you don’t have the money, another plan is to avoid having to choose which set piece to build and thus creating a discrepancy in style; instead you can create all these realities through more basic elements of stagecraft, like acting. Poor theater can be better theater; that’s why it was invented, not from necessity but intention.

’¦ because another problem, causally related to the pacing issue but less easily fixed, is the decision to stage the show as realistically as possible, on a small-theater budget. The result is a tech-heavy show that has to scrimp here and there. For half a million bucks, you can build a giant television that characters can pop in and out of (really beautiful work by set designer David Mauer and video designer Adam Flemming) and still have money to build a spaceship (barely there at all), a car (not there), a forest (ditto). But if you don’t have the money, another plan is to avoid having to choose which set piece to build and thus creating a discrepancy in style; instead you can create all these realities through more basic elements of stagecraft, like acting. Poor theater can be better theater; that’s why it was invented, not from necessity but intention.

But this brings us to another problem with this production: an uneven cast. Some of these performers are great, and make me believe (for instance) that they’re walking in the forest the production didn’t physically build. Some of them though, even while wearing elaborate costumes (by Michael Mullen), cannot convincingly convey that they are even actors. And so, despite the enticing premises upon which the show is built, the audience is taken out of the action time and again. It’s too bad; but then, it’s no Chappaquiddick.

But this brings us to another problem with this production: an uneven cast. Some of these performers are great, and make me believe (for instance) that they’re walking in the forest the production didn’t physically build. Some of them though, even while wearing elaborate costumes (by Michael Mullen), cannot convincingly convey that they are even actors. And so, despite the enticing premises upon which the show is built, the audience is taken out of the action time and again. It’s too bad; but then, it’s no Chappaquiddick.

photos by Brett Mayfield

1969: A Fantastical Odyssey Through The American Mindscape

Gatchu Productions at Theatre/Theater in Los Angeles

scheduled to end on April 29, 2012

for tickets call 323-930-0747 or visit www.1969theplay.com