MUCH ADO TO KNOW ITSELF

Sean Branney has been as lauded as a Los Angeles theater director can be, and Theatre Banshee has done some great work recently, so it’s disappointing to report that their new Merchant of Venice is, like Portia’s dowry boxes, a hash of gold, silver and lead.

In this story, the importer Antonio (Time Winters) frets over his literally at-sea fortunes even as he takes out a loan to help his friend Bassanio (Daniel Kaemon) woo the heiress Portia (Kirsten Kollender). Antonio’s business ventures founder, delighting the usurious moneylender Shylock (Barry Lynch), eager to exact revenge for Antonio’s anti-Semitic discourtesy. Shylock’s contract calls for the famous pound of flesh to recompense the defaulted monies, and it’s up to Portia, of all people, to save her lover’s friend from certain death. Between and among these heavy moments: jokes, puns, dancing and pratfalls. ‘Cause, you know, it’s a comedy.

Well, they don’t call it a problem play for nothing. The term applies in this case equally to the incredibility of the plot points and to the play’s unfitness for easy categorization. It also refers to the insoluble central conflicts and themes of the plays so labeled: unfaithfulness in Troilus and Cressida; social status in All’s Well That Ends Well. In Merchant, it’s race relations. In this world, money fixes everything but hate; even when Shylock is offered twice his original loan of ducats, he insists on collecting with his dagger. He’s been spat upon, had his character assassinated, had his business deals interfered with: all by Antonio, which nobody thinks is funny except Antonio.

So Shylock has good reasons for his vengeful attitude; Antonio, though, accounts for his behavior as benevolent intervention on behalf of those Shylock would have ruined financially. But the question of race is all over this play: everybody hates the Jew, not only for his avarice but because he’s a Jew. Shylock has a few choice words for Christians, too. Therefore a modern production invariably feels an obligation to address the play’s virulent racism, which is barely mitigated by a handful of speeches, all from Shylock himself; the poetry and truth of “if you prick us, do we not bleed?” does not overcome the dozens of slurs characters heap upon him. To his credit, Branney does not go out of his way either to excuse Shylock or to distinguish his behavior from his ethnicity; one (or, dreadfully, sometimes a combination) of these choices is de rigueur lately, and in the PC era has tended to pull all the focus of Merchant productions.

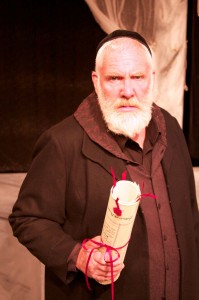

Branney has, however, allowed or directed the venerable Barry Lynch to play Shylock so consistently in one note, out of harmony with and yet not sharply enough delineated from the general levity of the production, that the nuance and variety of the character is lost in shrill, frowning shout. In fact a lot of people yell too much in this show, as if volume will make these old, old jokes funnier. (Extended slapstick involving a blind man, anyone?) This comedy’s chief comic relief – now there’s a structural problem! – is the servant Gobbo, whose bits Tim Stafford rushes too much to amuse and pitches too loud to pass unnoticed.

A play with this many good actors in it, yet featuring such all-over-the-map acting, points the familiar finger of fault at the director. Time Winters looks as if, in truth, he knows not why he is so sad, which is fine for Antonio but not fine for the actor. The character certainly has his share of preoccupation, but Winters’ is a vague sadness, and it is unclear much of the time just why he frets. This is a question that must be answered for the audience; like Hamlet’s vacillation, Antonio’s depression either explains itself or baffles its own purpose.

Kirsten Kollender plays an energetic and passionate Portia, and she, Kaemon and Branney create the most moving casket scene I’ve ever witnessed. But Kollender, so convincingly Irish in last year’s Dolly West’s Kitchen, needs to consult her copy of Speak with Distinction and ground herself in some Standard American Speech. She’s not alone in requiring the attentions of Edith Skinner: many a classical actor in Los Angeles looks the part but sounds like she’s from Topeka, spoiling the efforts she’s made to create character and separating herself from actors who can employ a neutral tongue (among them the charming eye-roller Ericka Winterrowd as Nerissa and Brett Mack, much better here as the buffoonish Gratiano than as the dour soldier in Dolly West). Kollender has excellent instincts and is in many ways a fine actress; if she devoted some of her abundant energies to a few technical elements, she might broaden both her vowels and the variety of roles she may convincingly voice.

There’s a much bigger issue with Portia, the play’s most dynamic role, that’s not as much the actress’s responsibility as her director’s. Branney sets up this Portia as a spoiled brat who flings used toothbrushes at her servants and delights in leading on suitors (James Schendel and Anthony Mark Barrow) only to crush their hopes. When she indulges in the cross-dressing inevitable to every Shakespearean comedy, posing as a lawyer on a lark, Portia should discover the boundaries of her influence. Up to this point, she has discussed Antonio’s pending execution according to the rules of her own life, in which privilege trumps all: her first impulse is to buy Shylock off, and she barely believes it when told that won’t work. In the courtroom, this overindulged girl ought to realize that by taking Antonio’s defense into her hands, she has displayed a Promethean hubris that nearly costs a man’s life. Kollender does play a sudden sense of gravity, but Branney has not framed her discovery as he has, for instance, some of the comic “takes” between Portia and Nerissa; and so Portia does not achieve a twinge of maturity, only (upon Antonio’s reprieve and Shylock’s commensurate devastation) another indication of her own potency. Thus her later game of teasing her husband about his faithfulness, and her own, lacks the depth of rueful experience, and the play ends as a silly farce instead of as a thoughtful comedy. This is especially disappointing given that she and Branney have just subjected the moneylender to a public humiliation massive in its implications.

It’s no simple task to make comedy from chestnuts, to inform that comedy with tragic elements, or to stage a big dance in the middle of it all. That any Merchant is even watchable is a great success, and Branney’s certainly is watchable. It’s just not very consistent; but then, neither is the writing. Even Shakespeare couldn’t get everything right.

photos by Donald Agnelli ©2012 Theatre Banshee

The Merchant of Venice

Theatre Banshee in Burbank (Los Angeles Theater)

scheduled to end on May 13

for tickets, visit http://www.theatrebanshee.org