YOUR OLD-AGE HOME FOR THE CLASSICS

Julia Rodriguez-Elliott’s production of Moliere’s The Bungler reminds me of nothing so much as the last two shows I’ve seen at A Noise Within this season. It’s not bad. It respects (not to say reveres, puts on a pedastal, suffocates with solicitude) its text, and presents it in an accessible staging. It features good-enough design, a competent original score, and a capable ensemble with a couple of standout actors. It also lacks the adventurous imagination necessary to really thrill, or to get the most from its source.

In this early rhymed-verse work by a great master, lovingly translated by national treasure Richard Wilbur, wily servant Mascarille (J.D. Cullum) assists titanically hapless master Lelie (the unerring Michael A. Newcomer) to avoid marrying lovely young Hippolyte (Kate Maher) and gain instead enslaved beauty Celie (Emily Kosloski). It’s a slight tale, full of small silliness and big fun; Ms Rodriguez-Elliott has stated her interpretation of the playwright’s intent thusly: “[T]his play doesn’t take on any big issues. It’s just sheer free-wheeling joy as Moliere’s homage to the spirit of commedia.” Depending on whom you wish to misquote, either God or the Devil is in the details, and embarking with such a vague analysis on as specific an endeavor as directing a play seems to have been the biggest risk she took with this show. In fact, in The Bungler Moliere does treat a pretty big issue – the universal tendency to be the destroyer of one’s own happiness – to an exhaustive going-over, and the director more or less finds her moments to address the point.

In this early rhymed-verse work by a great master, lovingly translated by national treasure Richard Wilbur, wily servant Mascarille (J.D. Cullum) assists titanically hapless master Lelie (the unerring Michael A. Newcomer) to avoid marrying lovely young Hippolyte (Kate Maher) and gain instead enslaved beauty Celie (Emily Kosloski). It’s a slight tale, full of small silliness and big fun; Ms Rodriguez-Elliott has stated her interpretation of the playwright’s intent thusly: “[T]his play doesn’t take on any big issues. It’s just sheer free-wheeling joy as Moliere’s homage to the spirit of commedia.” Depending on whom you wish to misquote, either God or the Devil is in the details, and embarking with such a vague analysis on as specific an endeavor as directing a play seems to have been the biggest risk she took with this show. In fact, in The Bungler Moliere does treat a pretty big issue – the universal tendency to be the destroyer of one’s own happiness – to an exhaustive going-over, and the director more or less finds her moments to address the point.

But a general design choice is not a whole-show concept. The production’s self-conscious stagey-ness (the old theater-within-a-theater conceit, executed by John Iacovelli) is interesting to look at, though what it adds thematically would fit into one of the set’s tiny teacups. Making a play not specifically about theater into a play about how theatrical life can be (a single line by a single character doesn’t justify an entire set) smacks of solipsism, one of my least favorite, most employed words to describe what happens on so many stages. Writers whose main characters tend to be writers are not to be forgiven for such a lack of outward vision, and neither are directors who don’t think outside of the (black) box, or the proscenium, or the thrust.

But a general design choice is not a whole-show concept. The production’s self-conscious stagey-ness (the old theater-within-a-theater conceit, executed by John Iacovelli) is interesting to look at, though what it adds thematically would fit into one of the set’s tiny teacups. Making a play not specifically about theater into a play about how theatrical life can be (a single line by a single character doesn’t justify an entire set) smacks of solipsism, one of my least favorite, most employed words to describe what happens on so many stages. Writers whose main characters tend to be writers are not to be forgiven for such a lack of outward vision, and neither are directors who don’t think outside of the (black) box, or the proscenium, or the thrust.

Ms Rodriguez-Elliott does go halfway toward a spirited, unequivocal presentation. A sound cue repeats, to the exasperation of one character, every time a certain country is mentioned; alas, this joke is not only hoary but one of very few that acknowledges or even assimilates into the all-the-world’s-a-stage concept. As slave-dealer Trufaldin, the always excellent William Dennis Hunt indicates a window by thrusting his head through a picture-frame held in his hands; this is clever and funny, but a moment later when he has to hold a gun too, the picture frame goes away though the window (apparently) remains. Trufaldin could juggle the window and the gun, ultimately choosing one or the other; he could try to fire the window instead of the gun; he could end up throwing the window itself in place of the bullet. Any of these stupid bits would execute thematic and, potentially, comic virtues, but no such business occurs; instead, an established device is dropped with no explanation, and an opportunity for the director to go all the way with the concept is missed.

Ms Rodriguez-Elliott does go halfway toward a spirited, unequivocal presentation. A sound cue repeats, to the exasperation of one character, every time a certain country is mentioned; alas, this joke is not only hoary but one of very few that acknowledges or even assimilates into the all-the-world’s-a-stage concept. As slave-dealer Trufaldin, the always excellent William Dennis Hunt indicates a window by thrusting his head through a picture-frame held in his hands; this is clever and funny, but a moment later when he has to hold a gun too, the picture frame goes away though the window (apparently) remains. Trufaldin could juggle the window and the gun, ultimately choosing one or the other; he could try to fire the window instead of the gun; he could end up throwing the window itself in place of the bullet. Any of these stupid bits would execute thematic and, potentially, comic virtues, but no such business occurs; instead, an established device is dropped with no explanation, and an opportunity for the director to go all the way with the concept is missed.

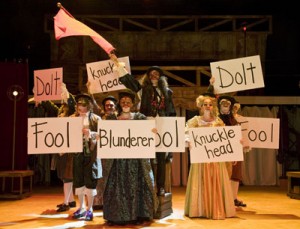

A similar half-measure: the swing players’ wearing commedia dell’arte masks, but moving en masse instead of embodying stock characters like Pantalone (though the show features several old fools) or Arlecchino (though it has a bunch of young ones, too). It’s a choice, and it does allow the cast to serve multiple roles without changing Angela Balogh Calin’s pretty costumes, but it begs the question of why the whole cast isn’t masked. Instead, while the named characters run around open-faced, the masked swing ensemble just gathers to sing David O melodies woven around Mascarille’s dialogue abusing his idiot master, songs that only serve to make redundant an already repetitive set of lines.

A similar half-measure: the swing players’ wearing commedia dell’arte masks, but moving en masse instead of embodying stock characters like Pantalone (though the show features several old fools) or Arlecchino (though it has a bunch of young ones, too). It’s a choice, and it does allow the cast to serve multiple roles without changing Angela Balogh Calin’s pretty costumes, but it begs the question of why the whole cast isn’t masked. Instead, while the named characters run around open-faced, the masked swing ensemble just gathers to sing David O melodies woven around Mascarille’s dialogue abusing his idiot master, songs that only serve to make redundant an already repetitive set of lines.

Among the talented ensemble, Mitchell Edmonds (as Lelie’s father Pandolfe) and Kevin Stidham (as Lelie’s rival Leandre) do particularly brilliant work with character and diction. Mr Stidham chews these couplets to wrest the most tasty meaning from each, though why he kept his English accent in a production where Standard American is the norm was unclear. Perhaps his director knows.

Among the talented ensemble, Mitchell Edmonds (as Lelie’s father Pandolfe) and Kevin Stidham (as Lelie’s rival Leandre) do particularly brilliant work with character and diction. Mr Stidham chews these couplets to wrest the most tasty meaning from each, though why he kept his English accent in a production where Standard American is the norm was unclear. Perhaps his director knows.

Mr Newcomer makes more comic hay of his few lines and appearances than one would have imagined possible, and easily owns a show that ought to be J.D. Cullum’s. As of the second performance, Mr Cullum still had a little trouble with Mascarille’s reams of dialogue, or else his anachronistically natural delivery, with its arbitrary starts and stops, made it seem so to me. But that’s another issue: his director has encouraged or allowed Mr Cullum, the audience’s guide and soliloquizing confidant, to be the sole actor with entirely modern vocal quirks. Given that his dialogue consists entirely of rhymed couplets, which he ignores, the choice is at least wrong-headed, especially matched with what I found to be a physical performance pitched 20% too high to be funny. Much of the mugging and sighing by this very competent actor might have seemed less necessary to him had he been encouraged to invest more heavily in the language, which after all is not exactly hack-work.

The thing is, I suspect this theater isn’t so much unimaginative as afraid to go all the way with concept; I’ll bet the decision to play Mascarille in modern idiom was a gesture of appeasement to an audience potentially put off by two unrelenting hours of rhyming speech. I think this director (A Noise Within’s Co-Producing Artistic Director) is capable of much better work, and that this theater is vastly more intelligent than these perfunctory indulgences suggest.

The thing is, I suspect this theater isn’t so much unimaginative as afraid to go all the way with concept; I’ll bet the decision to play Mascarille in modern idiom was a gesture of appeasement to an audience potentially put off by two unrelenting hours of rhyming speech. I think this director (A Noise Within’s Co-Producing Artistic Director) is capable of much better work, and that this theater is vastly more intelligent than these perfunctory indulgences suggest.

And I think it’s all about money: the fear of alienating – of “losing” – its season ticket holders has narrowed the horizons of many a revered institution. It’s a false concern. People who like theater really like theater, and they will accept a practical education in dramatics if they are shown its potential for excellence. They’ll thank you for showing it to them, and they’ll come away feeling smarter, and in fact being smarter, for the experience.

And I think it’s all about money: the fear of alienating – of “losing” – its season ticket holders has narrowed the horizons of many a revered institution. It’s a false concern. People who like theater really like theater, and they will accept a practical education in dramatics if they are shown its potential for excellence. They’ll thank you for showing it to them, and they’ll come away feeling smarter, and in fact being smarter, for the experience.

Is it wonderful that someone cares enough to stage Moliere and Shakespeare and Corneille in a comfortable 300-seat venue? In Los Angeles, in 2012? Yes. Is that enough to silence all voices hoping that A Noise Within will someday go further? No, it is not. This theater is proud of its “nineteen seasons in the black,” and in a year that has seen several Los Angeles theaters shuttered, that’s cause for congratulation. But there’s more than one reason A Noise Within stays afloat, and can conduct $13 million dollar renovations, et cetera. Consistent competence is one reason. Another is that no production in this beautiful space is nearly as likely to surprise its subscription audience as it is to comfort and reassure it. This theater aspires merely to entertain, and so with all its resources, it consistently somewhat disappoints the playgoer seeking groundbreaking interpretations of the classic works presented here.

photos by Craig Schwartz

The Bungler

A Noise Within in Pasadena (Los Angeles Theater)

scheduled to end on May 27, 2012

for tickets, visit http://www.ANoiseWithin.org

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

Bravo! Haven’t seen the play yet, but I am certain to agree.

As a new subscriber, I am finding that A Noise Within doesn’t surprise. They are satisfied to amuse, entertain and please; every play is a vaudeville riot of laughter and color. But I want theater that makes me feel, think, remember, and that which provokes or disturbs me. I want the voices on stage to be consistent, authoritative and appropriate to the work. Theater should never settle for pleasing.