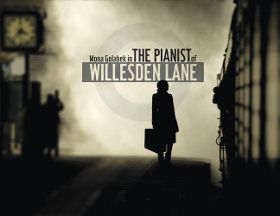

GRIEG, INTERRUPTED

The Pianist of Willesden Lane features world-class piano playing, a moving story, a performer who has mastered the art of the former but not of the latter, and a director who can’t tell the difference.

About ten years ago, pianist Mona Golabek wrote with Lee Cohen a children’s book about Golabek’s mother, Lisa Jura, and her experience as a musical aspirant and member of the Kindertransport, the post-Kristallnacht emigration of 10,000 Jewish children from Nazi-controlled territories to the British Isles. In this book Ms Jura journeys from wartime Vienna to a buzz-bombed London orphanage, to a uniform-sewing shop, and finally to the Royal Academy of Music. Though it hides within itself an inspiring tale of human endurance, The Children of Willesden Lane is not among my favorite youth-oriented Holocaust books, primarily because its simplistic style favors emotional terrorism over courageous storytelling. An eighth grader unsophisticated enough not to feel insulted by the book’s elementary language might come away with a sense of Lisa Jura’s personal suffering, but probably not of any overall truth about humanity’s capacity for evil and renewal. The book is written so specifically about one person’s experience, yet without the detail of character that might make it intimate or truly interesting, that for me it fails to achieve the universal appeal of, say, Elie Weisel’s Night or Anne Frank’s Diary.

Now Hershey Felder has adapted and staged a version of the book in the style of his own series of one-man piano shows, with Ms Golabek telling the story (in the character of her mother) from the keyboard of a magnificent Steinway. Or rather, I should say that she tells the best parts of the story at the piano, enticing snippets of everybody from Beethoven to Scriabin chosen for their relevance to the text and to its emotional life. However, Mr Hershey has directed her to stand from the piano every few bars, just as the music seizes us, and begin to act.

Now Hershey Felder has adapted and staged a version of the book in the style of his own series of one-man piano shows, with Ms Golabek telling the story (in the character of her mother) from the keyboard of a magnificent Steinway. Or rather, I should say that she tells the best parts of the story at the piano, enticing snippets of everybody from Beethoven to Scriabin chosen for their relevance to the text and to its emotional life. However, Mr Hershey has directed her to stand from the piano every few bars, just as the music seizes us, and begin to act.

Ms Golabek’s strengths in this production are her passion for her family history and her musicianship. Neither of these will I deign to question here. Her chops as a narrative actor are less sure. The decision to play her fourteen-year-old mother with wide eyes and a little-girl voice is not the choice of an actor, or a practiced storyteller; it is what a pianist might do if tasked with acting for little children. If this show were designed for children, nobody told the first-night audience composed almost exclusively of artistic, educated patrons over the age of fifty; but I do suspect that children would appreciate the presentational acting more than they would the slow, stately structure of this production.

Ms Golabek’s strengths in this production are her passion for her family history and her musicianship. Neither of these will I deign to question here. Her chops as a narrative actor are less sure. The decision to play her fourteen-year-old mother with wide eyes and a little-girl voice is not the choice of an actor, or a practiced storyteller; it is what a pianist might do if tasked with acting for little children. If this show were designed for children, nobody told the first-night audience composed almost exclusively of artistic, educated patrons over the age of fifty; but I do suspect that children would appreciate the presentational acting more than they would the slow, stately structure of this production.

Mr Felder’s clunky direction of his actor – stand up; declaim; sit down; play – is mirrored in his use of the gorgeous set by David A. Buess and Trevor Hay, ravishingly lighted by Christopher Rynne. Outsized gold picture frames suspended over the grand piano indicate by their emptiness that the playgoer is to be assailed by video projection before the night is out, and indeed she is subjected to a series of images cultural and historical, theoretically illustrating Ms Golabek’s soliloquy. That Greg Sowizdrzal’s newsreel footage of Jewish subjugation begins to repeat its loop before fading is as good a gauge as any of the depth behind Mr Felder’s intentions for it. One wonders how long audiences will accept such haphazard creativity from those supposed to be leading lights. Once more, in lieu of theatrical imagination we are fobbed off with devices better fitted to a less rigorous medium; and once more, a story with great potential is allowed to loll in the wash of its most obvious elements. By the time Erik Carstensen’s sound design drowns Ms Golabek’s piano with a canned piece of orchestrated Rachmaninoff, what illumination the evening possesses has already been darkened.

Mr Felder’s clunky direction of his actor – stand up; declaim; sit down; play – is mirrored in his use of the gorgeous set by David A. Buess and Trevor Hay, ravishingly lighted by Christopher Rynne. Outsized gold picture frames suspended over the grand piano indicate by their emptiness that the playgoer is to be assailed by video projection before the night is out, and indeed she is subjected to a series of images cultural and historical, theoretically illustrating Ms Golabek’s soliloquy. That Greg Sowizdrzal’s newsreel footage of Jewish subjugation begins to repeat its loop before fading is as good a gauge as any of the depth behind Mr Felder’s intentions for it. One wonders how long audiences will accept such haphazard creativity from those supposed to be leading lights. Once more, in lieu of theatrical imagination we are fobbed off with devices better fitted to a less rigorous medium; and once more, a story with great potential is allowed to loll in the wash of its most obvious elements. By the time Erik Carstensen’s sound design drowns Ms Golabek’s piano with a canned piece of orchestrated Rachmaninoff, what illumination the evening possesses has already been darkened.

A more lively and colorful version of this show might serve a nice dual purpose, to introduce very young people to the glories of classical piano and to the horrors of war. I prefer Ms Golabek’s interpretation of the more accessible Romantics – her Chopin and Grieg are enchanting, her Debussy transcendent – to her somewhat heavy-handed treatment of idiosyncratics like Scriabin and Rachmaninoff. But she clearly loves it all, and to hear a piano played at this level is to encounter a very high standard of art. The more frustrating, then, are the many moments in these ninety minutes when she takes her attention from the keys, abandoning her real gifts to indulge a less practiced set of skills. The primary gift of this production is that it compels one to see Ms Golabek in an entirely musical performance.

A more lively and colorful version of this show might serve a nice dual purpose, to introduce very young people to the glories of classical piano and to the horrors of war. I prefer Ms Golabek’s interpretation of the more accessible Romantics – her Chopin and Grieg are enchanting, her Debussy transcendent – to her somewhat heavy-handed treatment of idiosyncratics like Scriabin and Rachmaninoff. But she clearly loves it all, and to hear a piano played at this level is to encounter a very high standard of art. The more frustrating, then, are the many moments in these ninety minutes when she takes her attention from the keys, abandoning her real gifts to indulge a less practiced set of skills. The primary gift of this production is that it compels one to see Ms Golabek in an entirely musical performance.

photos by Michael Lamont

The Pianist of Willesden Lane

The Geffen Playhouse in Westwood (Los Angeles Theater)

scheduled to end on June 24, 2012Extended through September 15, 2012

for tickets, visit http://tickets.geffenplayhouse.com