Stage and Cinema sent Harvey Perr back to the east coast to catch up on this very busy time of the season in New York City theater, when new shows open one right after the other and Tony fever is in the air. Here’s a hearty and tasty stew of what he saw go down.

.

THE MAIN EVENT

Anyone who has ever thrilled to the intoxicating lure of literature must be eternally grateful to Elevator Repair Service. I admired and respected their adaptation of the first part of William Faulkner‘s The Sound and the Fury (April 7, 1928) more than I actually enjoyed it, but I knew their work, in bringing novels to the stage verbatim, was something quite special. I found each moment of The Select – in which they made of Ernest Hemingway‘s The Sun Also Rises one extended drunken spree from Paris to Spain – deliciously and imaginatively bizarre. But it is easy to understand why Gatz – the theatricalization of F. Scott Fitzgerald‘s The Great Gatsby, – is their signature piece: it is their most emotionally resonant work, primarily due to the fact that it is this novel that comes closer to perfection than the other two mentioned. And what a brilliant concept: Scott Shepherd (doing yeoman work that gets deeper and deeper under your skin as the long, tush-aching day hurtles along towards darkness) is an office worker who starts reading the book and, bit by bit, his fellow workers, moving in and around him, each performing his or her own duties, become the characters. What office worker, whether or not they know the novel, doesn’t dream of living the lives of people like Jay Gatsby and Daisy Buchanan? And the idea of playing the Jay/Daisy reunion as a farcical pas de trois, in which Nick is the third part of the equation, seems an extraordinary choice and beautifully prepares us for the unexpected. And the way it takes those dangerous curves as the novel gets more complex and disturbing reminded us that we were very much in the theater, even as we were plunging headlong into the heart of the novel. This was monumental work, the kind that comes along so rarely that it is more an event than a “play,” and I can’t imagine anyone who has sat through it who will not remember it as one of the unique theatergoing experiences of one’s lifetime.

Anyone who has ever thrilled to the intoxicating lure of literature must be eternally grateful to Elevator Repair Service. I admired and respected their adaptation of the first part of William Faulkner‘s The Sound and the Fury (April 7, 1928) more than I actually enjoyed it, but I knew their work, in bringing novels to the stage verbatim, was something quite special. I found each moment of The Select – in which they made of Ernest Hemingway‘s The Sun Also Rises one extended drunken spree from Paris to Spain – deliciously and imaginatively bizarre. But it is easy to understand why Gatz – the theatricalization of F. Scott Fitzgerald‘s The Great Gatsby, – is their signature piece: it is their most emotionally resonant work, primarily due to the fact that it is this novel that comes closer to perfection than the other two mentioned. And what a brilliant concept: Scott Shepherd (doing yeoman work that gets deeper and deeper under your skin as the long, tush-aching day hurtles along towards darkness) is an office worker who starts reading the book and, bit by bit, his fellow workers, moving in and around him, each performing his or her own duties, become the characters. What office worker, whether or not they know the novel, doesn’t dream of living the lives of people like Jay Gatsby and Daisy Buchanan? And the idea of playing the Jay/Daisy reunion as a farcical pas de trois, in which Nick is the third part of the equation, seems an extraordinary choice and beautifully prepares us for the unexpected. And the way it takes those dangerous curves as the novel gets more complex and disturbing reminded us that we were very much in the theater, even as we were plunging headlong into the heart of the novel. This was monumental work, the kind that comes along so rarely that it is more an event than a “play,” and I can’t imagine anyone who has sat through it who will not remember it as one of the unique theatergoing experiences of one’s lifetime.

THE PLAY IS STILL THE THING

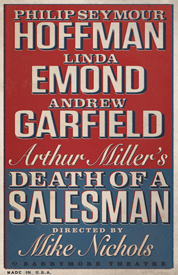

The best revival and the single most heartbreaking play on Broadway is Mike Nichols‘s restrained and intimate and finally explosive production of Arthur Miller‘s Death of a Salesman, a play which never fails, even after all these years, to unequivocally move an audience to gut-wrenching sobbing. (Tennessee Williams once said that if there was one American play he wished he could have written, it was Death of a Salesman.) The idea of doing the play on Jo Mielziner‘s original set, driven by the strains of Alex North‘s original haunting snatches of melody, could have had the effect of turning the play into a museum piece; but, instead, it reminds us of the kind of extraordinary design work that accompanied some of the theater’s greatest plays when they first came into our consciousness. It made one feel as if one was right there in 1949, seeing the play for the first time. And yet, in every other way, the play had an immediacy that seemed startlingly new. The entire cast was superb, with especially fine contributions by Bill Camp as Charley; Molly Price as the woman in Boston; and a truly heroic Happy in the form of a terrific young actor, whose name you’d do best to remember, Finn Wittrock. But its true claim to greatness lies in the shattering performances of Philip Seymour Hoffman, whose Willy Loman is a devastating mixture of a tired body, an overactive mind that can’t quite focus on getting things straight, a residue of long-standing anger and frustration that constantly backfires on itself, a selfishness, and even an occasional tenderness that shows up in ways that seem quite fresh, especially if you think that the play cannot yield a surprise or two; and of Linda Emond, who articulates Linda Loman’s abiding and unconditional love of Willy while giving shape to her personal anguish over what she knows and lives with; and, perhaps most persuasively of all, of Andrew Garfield, whose Biff is so vibrant with quiet intensity and coiled energy that when it is released, in the final confrontation with Willy, he practically forces you to get right into his soul and cry, as he does, with all the accumulated pain of a lifetime. This is a Death of a Salesman for the ages, for those who know it well and for anyone encountering it for the very first time.

The best revival and the single most heartbreaking play on Broadway is Mike Nichols‘s restrained and intimate and finally explosive production of Arthur Miller‘s Death of a Salesman, a play which never fails, even after all these years, to unequivocally move an audience to gut-wrenching sobbing. (Tennessee Williams once said that if there was one American play he wished he could have written, it was Death of a Salesman.) The idea of doing the play on Jo Mielziner‘s original set, driven by the strains of Alex North‘s original haunting snatches of melody, could have had the effect of turning the play into a museum piece; but, instead, it reminds us of the kind of extraordinary design work that accompanied some of the theater’s greatest plays when they first came into our consciousness. It made one feel as if one was right there in 1949, seeing the play for the first time. And yet, in every other way, the play had an immediacy that seemed startlingly new. The entire cast was superb, with especially fine contributions by Bill Camp as Charley; Molly Price as the woman in Boston; and a truly heroic Happy in the form of a terrific young actor, whose name you’d do best to remember, Finn Wittrock. But its true claim to greatness lies in the shattering performances of Philip Seymour Hoffman, whose Willy Loman is a devastating mixture of a tired body, an overactive mind that can’t quite focus on getting things straight, a residue of long-standing anger and frustration that constantly backfires on itself, a selfishness, and even an occasional tenderness that shows up in ways that seem quite fresh, especially if you think that the play cannot yield a surprise or two; and of Linda Emond, who articulates Linda Loman’s abiding and unconditional love of Willy while giving shape to her personal anguish over what she knows and lives with; and, perhaps most persuasively of all, of Andrew Garfield, whose Biff is so vibrant with quiet intensity and coiled energy that when it is released, in the final confrontation with Willy, he practically forces you to get right into his soul and cry, as he does, with all the accumulated pain of a lifetime. This is a Death of a Salesman for the ages, for those who know it well and for anyone encountering it for the very first time.

BEST NEW AMERICAN PLAY IN NEW YORK

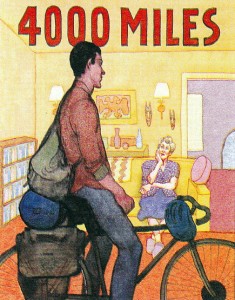

Amy Herzog‘s 4000 Miles is a newly-minted and poignantly observed drama of the relationship that ensues between the widow of a celebrated Marxist and her grandson, whose travels have taken him to his grandmother’s apartment in Greenwich Village; he is a young man who is as much defined by his liberalism as were his grandparents but who lives in a very different world. The beautifully calibrated production – under the extraordinarily sensitive direction of Daniel Aukin, and lit by Japhy Weideman so that the scenes of a homely New York existence take on the beauty of Vermeer paintings – offers sublime ensemble work, and particularly memorable contributions by Mary Louise Wilson who, as the grandmother, employs a remarkable walk that demonstrates the frailty of aging just as it projects the willingness to keep striding forward, and by Gabriel Ebert who, as the grandson, delivers the play’s most moving monologue (to give away its content would be shameful) almost entirely in darkness, and yet still manages to stop one’s heart.

Amy Herzog‘s 4000 Miles is a newly-minted and poignantly observed drama of the relationship that ensues between the widow of a celebrated Marxist and her grandson, whose travels have taken him to his grandmother’s apartment in Greenwich Village; he is a young man who is as much defined by his liberalism as were his grandparents but who lives in a very different world. The beautifully calibrated production – under the extraordinarily sensitive direction of Daniel Aukin, and lit by Japhy Weideman so that the scenes of a homely New York existence take on the beauty of Vermeer paintings – offers sublime ensemble work, and particularly memorable contributions by Mary Louise Wilson who, as the grandmother, employs a remarkable walk that demonstrates the frailty of aging just as it projects the willingness to keep striding forward, and by Gabriel Ebert who, as the grandson, delivers the play’s most moving monologue (to give away its content would be shameful) almost entirely in darkness, and yet still manages to stop one’s heart.

BEST NEW BRITISH PLAY IN NEW YORK

Nina Raine‘s Tribes, about a young man who grows up deaf (the remarkable Russell Harvard, who really is deaf) in a hearing family, is smart, argumentative, thorny, neurotic, vividly alive, and as tightly-knit as a family can possibly be. Billy, the young man, meets a young woman who, having lived her life with a deaf family, is now going deaf herself, and who encourages Billy to learn sign language, a project that stirs up the worst in Billy’s family, who feel that they have helped Billy by having him learn to read lips, and who have clearly ignored his need to be a part of a deaf community. It is strong stuff, this play, written with great care and feeling; but it is, above all, the production it is receiving that raises it to a level of art. All one needs to know, in fact, is that David Cromer is the director, a man with an unfailing eye for the truthful and the poetic. His people are so real that you feel, when you enter their house, as if you are an intruder, invading the privacy of their world. Mare Winningham and Jeff Perry are so good that you forget they are actors; and, though they play a couple who have been married for years and have three grown children, they even have about them the aura of still going to bed together and enjoying each other. Their faces are the ones I remember most of all when I reflect on my theater experiences this past April. And, once again, it was the lighting design that brought it so close to poetry: knowing how to illuminate darkness seems to be the central concern of many designers working in the theater these days, and Keith Parham will be remembered for playing so many scenes, in a play about reading lips, in the shadows of rooms in the still of the night.

Nina Raine‘s Tribes, about a young man who grows up deaf (the remarkable Russell Harvard, who really is deaf) in a hearing family, is smart, argumentative, thorny, neurotic, vividly alive, and as tightly-knit as a family can possibly be. Billy, the young man, meets a young woman who, having lived her life with a deaf family, is now going deaf herself, and who encourages Billy to learn sign language, a project that stirs up the worst in Billy’s family, who feel that they have helped Billy by having him learn to read lips, and who have clearly ignored his need to be a part of a deaf community. It is strong stuff, this play, written with great care and feeling; but it is, above all, the production it is receiving that raises it to a level of art. All one needs to know, in fact, is that David Cromer is the director, a man with an unfailing eye for the truthful and the poetic. His people are so real that you feel, when you enter their house, as if you are an intruder, invading the privacy of their world. Mare Winningham and Jeff Perry are so good that you forget they are actors; and, though they play a couple who have been married for years and have three grown children, they even have about them the aura of still going to bed together and enjoying each other. Their faces are the ones I remember most of all when I reflect on my theater experiences this past April. And, once again, it was the lighting design that brought it so close to poetry: knowing how to illuminate darkness seems to be the central concern of many designers working in the theater these days, and Keith Parham will be remembered for playing so many scenes, in a play about reading lips, in the shadows of rooms in the still of the night.

BEST NEW AMERICAN PLAY ON BROADWAY:

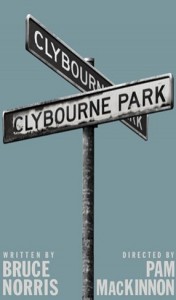

Clybourne Park by Bruce Norris is even better on Broadway than it was when I saw it earlier this year at the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles; Pam MacKinnon‘s direction is sharper and better suited to a proscenium stage and, if a performance or two has gotten broader, the cast, in general, is giving a funnier and sharper reading of the very smart text. I need not repeat myself about how I feel about the play, and, though being on Broadway is no longer what it used to be, and one can strive for more delicate results in a smaller venue, as TRIBES and 4000 MILES so beautifully prove, I, for one, am glad to see plays like CLYBOURNE PARK getting a larger audience (and I do not imagine it was better off-Broadway than it is on Broadway).

Clybourne Park by Bruce Norris is even better on Broadway than it was when I saw it earlier this year at the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles; Pam MacKinnon‘s direction is sharper and better suited to a proscenium stage and, if a performance or two has gotten broader, the cast, in general, is giving a funnier and sharper reading of the very smart text. I need not repeat myself about how I feel about the play, and, though being on Broadway is no longer what it used to be, and one can strive for more delicate results in a smaller venue, as TRIBES and 4000 MILES so beautifully prove, I, for one, am glad to see plays like CLYBOURNE PARK getting a larger audience (and I do not imagine it was better off-Broadway than it is on Broadway).

BEST NEW BRITISH PLAY ON BROADWAY

Okay, okay, One Man, Two Guvnors is really an adaptation of Carlo Goldoni‘s eighteenth-century farce The Servant Of Two Masters; but Richard Bean, the playwright, has updated it to take place in seedy old Brighton in the 1960s, and has done a swell job – and a wickedly witty one, I might add – of providing the play with a brand new and highly original life. But what makes this the funniest show in New York at the moment is that its inherent silliness is touched with genius. Director Nicholas Hytner – with fantastic help from Cal McCrystal‘s physical comedy direction – has pulled all the stops out to make this more hilarious than anything I’ve seen on Broadway since the production of Boeing-Boeing with Mark Rylance, and, to tell the truth, I can’t remember laughing this hard or this long at anything since the first time I saw the Marx Brothers in Duck Soup. And a good deal of it has to do with the shenanigans of its performers, who know how to take stereotypes and weave them into sacred fools you will never forget. James Corden plays the central character, the servant (one man) to two masters (two guvnors), and he is irrepressible and irresistible, a guy with mischief on his mind for all to see, but who, like Harry Langdon or Fatty Arbuckle, possesses an innocence so endearing that it makes his mischief-making even more wildly comic. Yet it is Tom Edden, as a literally and figuratively unbalanced geriatric waiter, whose pratfalls had me aching with laughter and, just when I thought the joke had gone as far as it could go, Edden would top it with yet another bit of gorgeously executed zaniness, to the point that I was finally exhausted from laughing. And there’s a sensational band – they call themselves The Craze – who, with the aid of some of the cast members, make such lively music together that One Man, Two Guvnors may also be the best new musical on Broadway.

Okay, okay, One Man, Two Guvnors is really an adaptation of Carlo Goldoni‘s eighteenth-century farce The Servant Of Two Masters; but Richard Bean, the playwright, has updated it to take place in seedy old Brighton in the 1960s, and has done a swell job – and a wickedly witty one, I might add – of providing the play with a brand new and highly original life. But what makes this the funniest show in New York at the moment is that its inherent silliness is touched with genius. Director Nicholas Hytner – with fantastic help from Cal McCrystal‘s physical comedy direction – has pulled all the stops out to make this more hilarious than anything I’ve seen on Broadway since the production of Boeing-Boeing with Mark Rylance, and, to tell the truth, I can’t remember laughing this hard or this long at anything since the first time I saw the Marx Brothers in Duck Soup. And a good deal of it has to do with the shenanigans of its performers, who know how to take stereotypes and weave them into sacred fools you will never forget. James Corden plays the central character, the servant (one man) to two masters (two guvnors), and he is irrepressible and irresistible, a guy with mischief on his mind for all to see, but who, like Harry Langdon or Fatty Arbuckle, possesses an innocence so endearing that it makes his mischief-making even more wildly comic. Yet it is Tom Edden, as a literally and figuratively unbalanced geriatric waiter, whose pratfalls had me aching with laughter and, just when I thought the joke had gone as far as it could go, Edden would top it with yet another bit of gorgeously executed zaniness, to the point that I was finally exhausted from laughing. And there’s a sensational band – they call themselves The Craze – who, with the aid of some of the cast members, make such lively music together that One Man, Two Guvnors may also be the best new musical on Broadway.

THE MOST DELIGHTFUL PRODUCTION OF A NEW AMERICAN PLAY ON BROADWAY

Peter and the Starcatcher is pure enchantment. You can read my full-length review, but I just want to say that when Christian Borle‘s Black Stache asked me to clap if I believed (not just in fairies, mind you, but just believing in the impossible), I was far more willing to do so than when Mary Martin‘s Peter Pan exhorted me to do the same thing years ago when I was much younger. This was a Peter Pan of a much tougher stripe. And, though I am much older now, this play located the child in me. I remain astonished that Disney was involved with a work this exciting.

Peter and the Starcatcher is pure enchantment. You can read my full-length review, but I just want to say that when Christian Borle‘s Black Stache asked me to clap if I believed (not just in fairies, mind you, but just believing in the impossible), I was far more willing to do so than when Mary Martin‘s Peter Pan exhorted me to do the same thing years ago when I was much younger. This was a Peter Pan of a much tougher stripe. And, though I am much older now, this play located the child in me. I remain astonished that Disney was involved with a work this exciting.

A PRODUCTION DEAR TO MY HEART

In the Labyrinth Theater Company’˜s production of Brett C. Leonard‘s Ninth and Joanie, Mark Wing-Davey‘s direction was easily the starkest and most uncompromising attempt to find the precise mood and pace of a playwright’s intentions that I came across; his work stands proudly alongside the work of David Cromer and Daniel Aukin, who were, after all, working with material that more immediately engaged the attention of an audience.

In the Labyrinth Theater Company’˜s production of Brett C. Leonard‘s Ninth and Joanie, Mark Wing-Davey‘s direction was easily the starkest and most uncompromising attempt to find the precise mood and pace of a playwright’s intentions that I came across; his work stands proudly alongside the work of David Cromer and Daniel Aukin, who were, after all, working with material that more immediately engaged the attention of an audience.

.

.

THERE IS NO EXCUSE FOR BAD ACTING IN NEW YORK

There is such a generous pool of acting talent in New York City that it is baffling to come across any play that is not, at the very least, filled with the most accomplished actors. Thus, it is hard to be kind to a play in which the acting is surprisingly flat or inept or just in need of stronger direction. Tennessee Williams, whose characters have given some of our best actors the opportunity to show themselves at their very best, is the biggest loser of the season. His “last” play, In Masks Outrageous and Austere, probably should never have seen the light of day, being unfinished, unresolved, and, despite moments here and there that are clearly the work of the greatest poet among American playwrights, written in a florid style so purplish with despair that it tends to sound like self-parody. And its ideas are so threadbare, as if Williams were trying to improve upon other works that were not well received, but which now seem like masterpieces; plays like The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore, whose central character, Flora Goforth, is not unlike this play’s Babe Foxworth, the rich woman who finds herself taken to some unknown country, along with her gay husband and his lover, in a 1983 which seems refracted through a sci-fi filter, as self-consciously directed by David Schweizer, who seems not to have trusted – with good reason – the play itself. As a recent production of A House Not Meant To Stand proved that Williams could still write with vigor, even in the twilight of his career, it is doubly unfortunate that his legacy is so tarnished by this play and by this production. The acting was execrable; the only credible actor in this enterprise is Shirley Knight; unfortunately, not only does she have nobody to play against, but, left on her own, she seems restless and tentative, and, quite simply, not fully armed enough to play the kind of tough bird that Williams probably saw a lot of himself in.

There is such a generous pool of acting talent in New York City that it is baffling to come across any play that is not, at the very least, filled with the most accomplished actors. Thus, it is hard to be kind to a play in which the acting is surprisingly flat or inept or just in need of stronger direction. Tennessee Williams, whose characters have given some of our best actors the opportunity to show themselves at their very best, is the biggest loser of the season. His “last” play, In Masks Outrageous and Austere, probably should never have seen the light of day, being unfinished, unresolved, and, despite moments here and there that are clearly the work of the greatest poet among American playwrights, written in a florid style so purplish with despair that it tends to sound like self-parody. And its ideas are so threadbare, as if Williams were trying to improve upon other works that were not well received, but which now seem like masterpieces; plays like The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore, whose central character, Flora Goforth, is not unlike this play’s Babe Foxworth, the rich woman who finds herself taken to some unknown country, along with her gay husband and his lover, in a 1983 which seems refracted through a sci-fi filter, as self-consciously directed by David Schweizer, who seems not to have trusted – with good reason – the play itself. As a recent production of A House Not Meant To Stand proved that Williams could still write with vigor, even in the twilight of his career, it is doubly unfortunate that his legacy is so tarnished by this play and by this production. The acting was execrable; the only credible actor in this enterprise is Shirley Knight; unfortunately, not only does she have nobody to play against, but, left on her own, she seems restless and tentative, and, quite simply, not fully armed enough to play the kind of tough bird that Williams probably saw a lot of himself in.

As for the not exactly all-black version of A Streetcar Named Desire, Emily Mann, who directed, shows no interest in discovering anything new in the play, and she has cast it with not-untalented people who work hard, but to little avail; they have neither come anywhere near catching the poetry of the play nor have they been directed to do so. I hope nobody gets the idea that A Streetcar Named Desire isn’t every bit as great a play as Death of a Salesman but, like all great plays, attention must be paid to the talents that bring them to life – or not.

As for the not exactly all-black version of A Streetcar Named Desire, Emily Mann, who directed, shows no interest in discovering anything new in the play, and she has cast it with not-untalented people who work hard, but to little avail; they have neither come anywhere near catching the poetry of the play nor have they been directed to do so. I hope nobody gets the idea that A Streetcar Named Desire isn’t every bit as great a play as Death of a Salesman but, like all great plays, attention must be paid to the talents that bring them to life – or not.

One might have guessed that An Early History of Fire, David Rabe‘s first play in nine years, was written many years ago, long before the great works that established him as one of our better playwrights. Seen that way, as something pulled from a trunk, it might even have a certain charm, as it shows the rite of passage of a young man during a potent moment in our history,  when the world was beginning to change at a very rapid rate; and it hasn’t been helped by Jo Bonney‘s flaccid direction and a cast that seems not yet to have graduated yet from acting school. They spoke the words but gave no sign of the characters speaking them, except in the most rudimentary ways; it’s what I would call – allow me to coin this term – neo-sitcom.

when the world was beginning to change at a very rapid rate; and it hasn’t been helped by Jo Bonney‘s flaccid direction and a cast that seems not yet to have graduated yet from acting school. They spoke the words but gave no sign of the characters speaking them, except in the most rudimentary ways; it’s what I would call – allow me to coin this term – neo-sitcom.

MUSICALS

The bottle of champagne that is Nice Work If You Can Get It doesn’t really get uncorked until the second act. And when it does, it may not be Dom Perignon, but it’s a heady brew just the same. Let loose – its plot purposely getting dumber in ways that are supposed to remind you of the kind of carefree musicals of yesteryear it clearly wants to be; its characters finally just settling down to having some fun; and its wonderful string of great Gershwin tunes (lovingly orchestrated by Bill Elliot) getting bounced around like some ineffable something in the air – Nice Work lets you leave the theater in a buoyant mood, possibly humming whatever song you loved the most from the show. What more could you ask for? It’s in the second act that Judy Kaye sings “By Strauss” as counterpoint to Michael McGrath‘s “Sweet and Lowdown,” and, together, they stop the show. It’s in the second act that the dancers, under-utilized in the first act, get to strut their stuff. It’s in the second act that Kelli O’Hara sings “But Not For Me” and makes you swoon. It’s in the second act that the great trouper, Estelle Parsons, as the most peculiar deus ex machina imaginable, finally shows up and saves the day without singing a single note. Everything good that happens, it turns out, happens in that second act. The first act offers hints that, when uncorked, the champagne will be effervescent and not flat, as when Jennifer Laura Thompson, surrounded by chorus girls who pop out of her bubble bath, sings – sounding an awful lot like Madeline Kahn – the fizzy “Delishious.” Or when Robyn Hurder and Chris Sullivan prove to be both goofy and sexy singing “Do It Again” (but again, in the second act, they do even better with “Blah, Blah, Blah”). But you spend too much time wondering if Matthew Broderick is the right choice to play a boozed-up, much-married bon vivant of the roaring 20s or why anyone would ask Kelli O’Hara to play a boyish-looking bootlegger, looking more like a newsboy than a dangerous criminal. But then Kathleen Marshall has conceived a dance for the two of them, up and down a magnificent staircase, to “‘S Wonderful,” one can finally stop worrying and warm up to their charms. Wanting its innate gaiety to light up the stage from the beginning, it seems to take such a long time to get there. But it’s definitely nice work when you finally get it.

The bottle of champagne that is Nice Work If You Can Get It doesn’t really get uncorked until the second act. And when it does, it may not be Dom Perignon, but it’s a heady brew just the same. Let loose – its plot purposely getting dumber in ways that are supposed to remind you of the kind of carefree musicals of yesteryear it clearly wants to be; its characters finally just settling down to having some fun; and its wonderful string of great Gershwin tunes (lovingly orchestrated by Bill Elliot) getting bounced around like some ineffable something in the air – Nice Work lets you leave the theater in a buoyant mood, possibly humming whatever song you loved the most from the show. What more could you ask for? It’s in the second act that Judy Kaye sings “By Strauss” as counterpoint to Michael McGrath‘s “Sweet and Lowdown,” and, together, they stop the show. It’s in the second act that the dancers, under-utilized in the first act, get to strut their stuff. It’s in the second act that Kelli O’Hara sings “But Not For Me” and makes you swoon. It’s in the second act that the great trouper, Estelle Parsons, as the most peculiar deus ex machina imaginable, finally shows up and saves the day without singing a single note. Everything good that happens, it turns out, happens in that second act. The first act offers hints that, when uncorked, the champagne will be effervescent and not flat, as when Jennifer Laura Thompson, surrounded by chorus girls who pop out of her bubble bath, sings – sounding an awful lot like Madeline Kahn – the fizzy “Delishious.” Or when Robyn Hurder and Chris Sullivan prove to be both goofy and sexy singing “Do It Again” (but again, in the second act, they do even better with “Blah, Blah, Blah”). But you spend too much time wondering if Matthew Broderick is the right choice to play a boozed-up, much-married bon vivant of the roaring 20s or why anyone would ask Kelli O’Hara to play a boyish-looking bootlegger, looking more like a newsboy than a dangerous criminal. But then Kathleen Marshall has conceived a dance for the two of them, up and down a magnificent staircase, to “‘S Wonderful,” one can finally stop worrying and warm up to their charms. Wanting its innate gaiety to light up the stage from the beginning, it seems to take such a long time to get there. But it’s definitely nice work when you finally get it.

Then there is that other Gershwin musical, the one they are now calling The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess. Again, things don’t start out promisingly. The overture sounds tinny and abbreviated. The set has a generic feel to it (I’ve never cared if Catfish Row was a real place or not; there was always something mythic and folkloric about it; but no matter how you see it, it cries out for color and character). And, as it progresses, you begin to wonder if the original intentions of this production were compromised and finally neutered by Stephen Sondheim‘s harsh attitude towards it before it even took flight. This is not the grand operatic version – the sung parts are now spoken, the thrilling “Buzzard Song” has been cut, the orchestra has been pared down – but it is still an opera, the one that was created by George and Ira Gershwin in intense and magnificent collaboration with DuBose and Dorothy Heyward, and the voices are so good that anyone seeing it for the first time is bound to get a very real sense of its greatness, even if it doesn’t deliver the goods until – you guessed it – the second act. (What is it about both Gershwin musicals that it takes so long to lift them off the all-too-solid ground? It’s surely not for want of great music.) But that’s when the magic begins, and it begins because Audra McDonald, who can’t seem to do anything wrong, becomes, quite simply, the best Bess one is likely to see for quite some time to come. Not only does Ms. McDonald sing with a gorgeous power and fluidity, she is, as ever, offering up an absolutely great piece of acting as well. The inner turmoil that Bess manifests is partnered with a lyrical understanding of how that turmoil transforms into song. Her “What You Want With Bess?” – as she is slowly surrendering herself, unwillingly at first but finally unable to resist the brute force of her estranged lover, Crown – is disturbingly sensual and heartbreakingly liquid. And, not quite coming out of the terrible place the encounter has put her in, when she sings “I Loves You, Porgy,” she unleashes all the real emotion that lies beneath the animal passion she has given into. And, even when Sporting Life (David Alan Grier) sings “There’s A Boat That’s Leaving Soon” (and it’s quite an insinuating interpretation), it’s Audra McDonald you are watching, because her response is so astonishingly natural that you almost want to take her in your arms and keep her from giving into that “magic dust” that will take her to New York and a way of life far from Catfish Row and her now beloved Porgy. Norm Lewis, sans goat and wagon, but still ungainly in his braces, is a warm Porgy, and the contrast between him and Phillip Boykin‘s hot Crown, help to clarify the tensions swirling around inside McDonald’s Bess. Since this production owes so much to Sondheim’s stinging criticism, the race for the Best Musical Revival Tony Award is further heightened by the fact that The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess and Sondheim’s Follies are competing against each other. Since neither production seems a sterling example of what makes each musical so great, I do think Follies is the better show, but there is no argument about who gives the best performance by an actress in a musical. Need I say her name again?

Then there is that other Gershwin musical, the one they are now calling The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess. Again, things don’t start out promisingly. The overture sounds tinny and abbreviated. The set has a generic feel to it (I’ve never cared if Catfish Row was a real place or not; there was always something mythic and folkloric about it; but no matter how you see it, it cries out for color and character). And, as it progresses, you begin to wonder if the original intentions of this production were compromised and finally neutered by Stephen Sondheim‘s harsh attitude towards it before it even took flight. This is not the grand operatic version – the sung parts are now spoken, the thrilling “Buzzard Song” has been cut, the orchestra has been pared down – but it is still an opera, the one that was created by George and Ira Gershwin in intense and magnificent collaboration with DuBose and Dorothy Heyward, and the voices are so good that anyone seeing it for the first time is bound to get a very real sense of its greatness, even if it doesn’t deliver the goods until – you guessed it – the second act. (What is it about both Gershwin musicals that it takes so long to lift them off the all-too-solid ground? It’s surely not for want of great music.) But that’s when the magic begins, and it begins because Audra McDonald, who can’t seem to do anything wrong, becomes, quite simply, the best Bess one is likely to see for quite some time to come. Not only does Ms. McDonald sing with a gorgeous power and fluidity, she is, as ever, offering up an absolutely great piece of acting as well. The inner turmoil that Bess manifests is partnered with a lyrical understanding of how that turmoil transforms into song. Her “What You Want With Bess?” – as she is slowly surrendering herself, unwillingly at first but finally unable to resist the brute force of her estranged lover, Crown – is disturbingly sensual and heartbreakingly liquid. And, not quite coming out of the terrible place the encounter has put her in, when she sings “I Loves You, Porgy,” she unleashes all the real emotion that lies beneath the animal passion she has given into. And, even when Sporting Life (David Alan Grier) sings “There’s A Boat That’s Leaving Soon” (and it’s quite an insinuating interpretation), it’s Audra McDonald you are watching, because her response is so astonishingly natural that you almost want to take her in your arms and keep her from giving into that “magic dust” that will take her to New York and a way of life far from Catfish Row and her now beloved Porgy. Norm Lewis, sans goat and wagon, but still ungainly in his braces, is a warm Porgy, and the contrast between him and Phillip Boykin‘s hot Crown, help to clarify the tensions swirling around inside McDonald’s Bess. Since this production owes so much to Sondheim’s stinging criticism, the race for the Best Musical Revival Tony Award is further heightened by the fact that The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess and Sondheim’s Follies are competing against each other. Since neither production seems a sterling example of what makes each musical so great, I do think Follies is the better show, but there is no argument about who gives the best performance by an actress in a musical. Need I say her name again?