OF GOOD TURNS AND SCREWINGS

All emotional reaction comes filtered through prerequisite knowledge: the sound of a crying baby is annoying, unless it’s your baby, in which case that sound may make you feel anything from relief (“It’s your turn, babe”) to terror (“I thought he was napping – that sounded like it came from the back yard!”). Henry James, the American master of repression, dripped his morality through a screen of spider web-complex prejudice and allusion such that to appreciate his genius – to get anything at all from him — one must already have read about a thousand books by less forbidding authors. And with certain of his stories, none more than 1898’s ghost story The Turn of the Screw, the action is so far obfuscated by the language and intent of its author that a hundred years’ analyses have not yet agreed on what happens in it. It may be that James was too prudish to be explicit, or too refined; a broad view of his work and life reveals a very sensitive writer perhaps less concerned with being subtle than afraid of being thought gauche. That said, it would take a braver critic than I to say that The Turn of the Screw turned out this way by accident.

So we don’t know for certain, in James’s novella, whether the new governess of two traumatized children really is menaced by the ghosts of their perverted tormentors, or whether the danger comes, in equal parts panic and desire, from her own sex-starved imagination. Jeffrey Hatcher’s 1997 two-actor stage adaptation makes definite choices about the action, but leaves some ambiguity for the audience to consider. This would be fine as long as the play were so constructed that it lent itself to a good scare. But the playwright has missed an important difference between horror and terror. Horror can exist wholly independent of fear, and so it is in his adaptation: we hear terrible stories, we are presented with awful shocks to our sensibilities, but without a creeping tide of peril, these elements disgust more than frighten. There isn’t enough of a ramp from the weirdly bucolic opening to the final grand guignol freakshow, and thus hardly any mounting suspense. Instead, an intellectually connected series of events produces a drama more engaging to its characters than for its audience – and extraordinarily difficult for its actors.

Dan Spurgeon’s very good Visceral Company production goes nearly as far as direction and acting can toward fixing some of these problems. Mr Spurgeon uses Dave Sousa’s penumbric lighting of Tyler Aaron Travis’s line-drawn set to good advantage. He keeps the pace up without rushing his well-framed moments, and makes much of single-flickering-candle-in-the-cellar-type effects. I’m not a fan of the decision to turn an actor to the wall when he’s not being used in a scene, a problem seemingly easy to solve with a scrim or a masking piece of set dressing or a simple exit. An actor in sleep mode may as well be offstage. But this director understands the purpose of the larger exercise better than the playwright, and that the evening largely works is to his credit and to that of his two fine actors.

Dan Spurgeon’s very good Visceral Company production goes nearly as far as direction and acting can toward fixing some of these problems. Mr Spurgeon uses Dave Sousa’s penumbric lighting of Tyler Aaron Travis’s line-drawn set to good advantage. He keeps the pace up without rushing his well-framed moments, and makes much of single-flickering-candle-in-the-cellar-type effects. I’m not a fan of the decision to turn an actor to the wall when he’s not being used in a scene, a problem seemingly easy to solve with a scrim or a masking piece of set dressing or a simple exit. An actor in sleep mode may as well be offstage. But this director understands the purpose of the larger exercise better than the playwright, and that the evening largely works is to his credit and to that of his two fine actors.

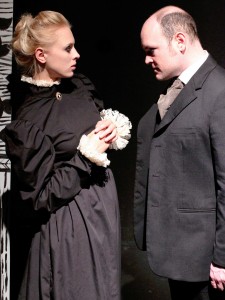

As the governess, Amelia Gotham successfully displays the gamut of poses from hesitant virgin to rapacious hellion; and as every other character, Nich Kauffman resists the temptation to show off his chops in a job that fairly screams for curtain-chewing. Neither of them is done any favors by this fits-and-starts script, and their ability to quickly summon the appropriate facial expression and tone of voice is impressive. Both could benefit from being about 15% surer of their dialects, and the mood would be easier to sustain if they didn’t each fumble a line here and there; these faults are not unrelated to each other, and also to the general awkwardness of the script. But this production is a showcase for a sleekly engaging kind of acting that both these actors can do very well.

As the governess, Amelia Gotham successfully displays the gamut of poses from hesitant virgin to rapacious hellion; and as every other character, Nich Kauffman resists the temptation to show off his chops in a job that fairly screams for curtain-chewing. Neither of them is done any favors by this fits-and-starts script, and their ability to quickly summon the appropriate facial expression and tone of voice is impressive. Both could benefit from being about 15% surer of their dialects, and the mood would be easier to sustain if they didn’t each fumble a line here and there; these faults are not unrelated to each other, and also to the general awkwardness of the script. But this production is a showcase for a sleekly engaging kind of acting that both these actors can do very well.

photos by Dara Osborne

The Turn of the Screw

The Visceral Company at the Underground Theatre in Hollywood

scheduled to end on June 9, 2012 Remount plays September 20-October 27, 2012

for tickets, visit http://www.thevisceralcompany.com