SOUR SATURDAY

A troubled production is a sad spectacle, especially at a venerable theater that does some fine work. PRT’s new staging of the John Steinbeck novel Sweet Thursday tries hard, and that it fails to coalesce does not negate the good stuff that makes up the mess. It does, however, make for a dull and ungainly three hours.

A cursory examination of the program reveals that co-adaptor Robb Derringer was set to play the leading role of Doc, a part now played by someone else. Opening night was pushed back by a week, twice, and one may assume what one likes about that. PRT demurely states that Mr. Derringer has left the production for personal reasons, while director and co-adaptor Matt McKenzie has remained. One may make assumptions about that, too, if one is inclined. But there is no conjecture involved in the product presented Saturday night. Theory is unnecessary in the presence of abundant evidence.

A cursory examination of the program reveals that co-adaptor Robb Derringer was set to play the leading role of Doc, a part now played by someone else. Opening night was pushed back by a week, twice, and one may assume what one likes about that. PRT demurely states that Mr. Derringer has left the production for personal reasons, while director and co-adaptor Matt McKenzie has remained. One may make assumptions about that, too, if one is inclined. But there is no conjecture involved in the product presented Saturday night. Theory is unnecessary in the presence of abundant evidence.

Mr. McKenzie, who did a very nice job recently marshaling Sarah’s War, this time would seem to have had too much on his hands to do any of it adequately. Technical elements plagued Sarah’s War in its run at the Hudson, in that case mostly video and sound issues. With Sweet Thursday, Charles Erven’s handsome, inefficient, many-hinged-and-wheeled set (the employment of which, from the third row at least, appeared dangerously close to breaking an actor’s leg) stands as a good metaphor for the production generally: its ambitions are too big for its capacity to realize them.

Mr. McKenzie, who did a very nice job recently marshaling Sarah’s War, this time would seem to have had too much on his hands to do any of it adequately. Technical elements plagued Sarah’s War in its run at the Hudson, in that case mostly video and sound issues. With Sweet Thursday, Charles Erven’s handsome, inefficient, many-hinged-and-wheeled set (the employment of which, from the third row at least, appeared dangerously close to breaking an actor’s leg) stands as a good metaphor for the production generally: its ambitions are too big for its capacity to realize them.

The novel, a sweet, short fluff originally written as much as a ramp-up to Broadway adaptation as a sequel to Cannery Row, sprawls its motley cast of losers in a rich fairy-tale landscape. Following World War II, biologist and skid row intellectual Doc returns to the tide pools of Monterey, California. The bums and whores who constitute his friends decide that he needs a woman. The whorehouse has a rookie hooker. Et voila.

How long should that story take to tell? Even including period musical accompaniment by cast members? Not three hours. Nearly every beat in the book is in this play, needed or (in most cases) not. Mr. Derringer and Mr. McKenzie’s script has too many scenes by a factor of two, including at least a half-dozen in which the audience is informed that what Doc needs is a woman. A “seer” and an astrologer tell us, separately of course. Several winos tell us – some of them several times apiece. Doc’s grocer tells us. Doc’s philanthropist buddy tells us. Doc tells us himself. Any three of these would suffice.

How long should that story take to tell? Even including period musical accompaniment by cast members? Not three hours. Nearly every beat in the book is in this play, needed or (in most cases) not. Mr. Derringer and Mr. McKenzie’s script has too many scenes by a factor of two, including at least a half-dozen in which the audience is informed that what Doc needs is a woman. A “seer” and an astrologer tell us, separately of course. Several winos tell us – some of them several times apiece. Doc’s grocer tells us. Doc’s philanthropist buddy tells us. Doc tells us himself. Any three of these would suffice.

Which points up another adaptation issue: Mr. Derringer and Mr. McKenzie have included just about all the characters, even referencing some from Cannery Row that were left out of its follow-up novel. Some actors met at the top of the show have literally hours in which to play cards or go surfing at Venice Beach or read a hundred pages of Dostoyevsky before we can greet them again. This will not do. If, in adaptation, one cannot be too brutal, one certainly also must not be precious. Consolidation is a virtue. So is expedience.

Which points up another adaptation issue: Mr. Derringer and Mr. McKenzie have included just about all the characters, even referencing some from Cannery Row that were left out of its follow-up novel. Some actors met at the top of the show have literally hours in which to play cards or go surfing at Venice Beach or read a hundred pages of Dostoyevsky before we can greet them again. This will not do. If, in adaptation, one cannot be too brutal, one certainly also must not be precious. Consolidation is a virtue. So is expedience.

The narrative simply doesn’t have tale or theme enough to warrant all this, plus an inexplicable, barbaro-Spanish seventh-inning full-company dance number that, while well-executed, propels nothing more than impatience. Nor does the show benefit from a performance style pitched at little children. A few of the actors, perhaps five or six of them, understand the requirements of heightened but not quite presentational theater. The rest appear to have heard a director’s note about speed or intensity or larger-than-life and done as told. But a fairy tale for grown-ups may safely be offered in a grown-up manner. When I read the book, I didn’t need to imagine the characters wagging their heads and popping their eyes all the time. I don’t think I could have read it if I had.

The narrative simply doesn’t have tale or theme enough to warrant all this, plus an inexplicable, barbaro-Spanish seventh-inning full-company dance number that, while well-executed, propels nothing more than impatience. Nor does the show benefit from a performance style pitched at little children. A few of the actors, perhaps five or six of them, understand the requirements of heightened but not quite presentational theater. The rest appear to have heard a director’s note about speed or intensity or larger-than-life and done as told. But a fairy tale for grown-ups may safely be offered in a grown-up manner. When I read the book, I didn’t need to imagine the characters wagging their heads and popping their eyes all the time. I don’t think I could have read it if I had.

Pacing, too, may be counted among the issues for Mr. McKenzie to tackle next. Early on, when multiple characters are introduced by clomping onstage to deliver a single line and then clomping back off, no overlap occurs. No other character starts on until the previous has completely exited. This is poor generalship and speaks to larger conceptual issues like “whose story are we telling” and “what are the essentials of that story” and “how long before the chairs feel really uncomfortable?”

Pacing, too, may be counted among the issues for Mr. McKenzie to tackle next. Early on, when multiple characters are introduced by clomping onstage to deliver a single line and then clomping back off, no overlap occurs. No other character starts on until the previous has completely exited. This is poor generalship and speaks to larger conceptual issues like “whose story are we telling” and “what are the essentials of that story” and “how long before the chairs feel really uncomfortable?”

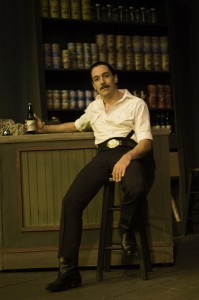

There are good things in this show. Lela Loren, Dennis Madden, Kevin Fabian, George Villas and Lee de Broux all present grounded human characters, and are given role enough to engage in living moments onstage. But this is a cast of close to twenty actors, half of whom just don’t have any good reason to be here, especially as inappropriately as they’ve been directed to behave. Loud and shrill is not enough to keep an audience awake.

photos by Vitor Martins

Sweet Thursday

Pacific Resident Theatre in Venice (Los Angeles Theater)

scheduled to end on September 30, 2012 EXTENDED through October 28, 2012

for tickets, visit http://www.PacificResidentTheatre.com