UNDER MY SHOE

If the comedy in Under My Skin were any more broad, it would require a wider stage than the one at the Pasadena Playhouse. If the play were any less funny, it would have to wear a black armband. But it is well-intentioned, and so this blithely degrading show cannot be despised with the totality of vehemence it would otherwise deserve.

If the comedy in Under My Skin were any more broad, it would require a wider stage than the one at the Pasadena Playhouse. If the play were any less funny, it would have to wear a black armband. But it is well-intentioned, and so this blithely degrading show cannot be despised with the totality of vehemence it would otherwise deserve.

The script for Under My Skin comes from a long line of American farce, a line that bred itself out and devolved into television situation comedy. This is not always so bad; there have always been good sitcoms, from The Honeymooners to Barney Miller to Curb Your Enthusiasm, in whose writer’s rooms a playwright might hone the craft of storytelling beyond characters like the old Jew who says “tuchus” and other used-tissue gags. But writers Robert Sternin & Prudence Fraser spent thirty years writing for the other sort of sitcom, cultural blight including Who’s the Boss and The Nanny. Taking note of this pedigree would almost prepare one for the assault on creative intelligence that is Under My Skin. Almost, because by the Third Millennium, one might expect that characters this shrill, situations this familiar, stereotypes this damnable, would have been long since buried under the Cardboard Cemetery.

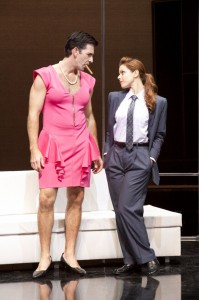

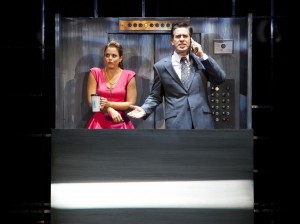

To wit: sweet, hardworking, struggling-to-make-ends-meet single mom Melody Dent (Erin Cardillo) and callous, swaggering, born-to-wealth insurance company CEO Harrison Badish (Matt Walton) switch bodies in a heavenly clerical error, and, as the most odiously pandering character puts it, the rich man is forced by “the good Lord” to “walk a mile in some girl’s pumps.” The character into whose mouth Sternin & Fraser lay this egg (an unnecessary moral, given the obnoxious teachable moments that precede it) is not merely the play’s single person of color in an otherwise Nordic New York City. Are you ready for whiplash? She’s also a sassy black civil-servant-class Angel (Yvette Cason) complete with no-backtalk index-finger (“Uh, uh, uh, honey”) and a free hand always ready to perch on one hip (“Don’t be snappin’ at me… It’s not that easy bringing someone back from the dead. Although it worked on Liza Minnelli”). Audiences might be forgiven for thinking they have died and fallen to a hell based on 1986, if indeed they retain the power of thought after this many double-takes, slow burns, and man-trying-to-walk-in-heels pratfalls.

To wit: sweet, hardworking, struggling-to-make-ends-meet single mom Melody Dent (Erin Cardillo) and callous, swaggering, born-to-wealth insurance company CEO Harrison Badish (Matt Walton) switch bodies in a heavenly clerical error, and, as the most odiously pandering character puts it, the rich man is forced by “the good Lord” to “walk a mile in some girl’s pumps.” The character into whose mouth Sternin & Fraser lay this egg (an unnecessary moral, given the obnoxious teachable moments that precede it) is not merely the play’s single person of color in an otherwise Nordic New York City. Are you ready for whiplash? She’s also a sassy black civil-servant-class Angel (Yvette Cason) complete with no-backtalk index-finger (“Uh, uh, uh, honey”) and a free hand always ready to perch on one hip (“Don’t be snappin’ at me… It’s not that easy bringing someone back from the dead. Although it worked on Liza Minnelli”). Audiences might be forgiven for thinking they have died and fallen to a hell based on 1986, if indeed they retain the power of thought after this many double-takes, slow burns, and man-trying-to-walk-in-heels pratfalls.

But after well over an hour of enervating schtick, not limited to the erstwhile Barney Miller himself, Hal Linden, as the old Jew who has to say, not merely “tuchus,” but “chicken tuchus;” Mr. Walton’s extremely masculine frame filling out a dress (and those very low heels, almost flats – perhaps the actor bribed costumer Kate Bergh, who aimed at subtlety in no other detail); a fake-breast-hefting character named Nanette (Megan Sikora) being told (yes, this happened), “No, no, Nanette!”… after, I say, a first act stuffed with this offensively inoffensive white-bread pudding, this show becomes an issue play.

Or rather, it thinks it does. Suddenly, and not before the act break when it could create some suspense but after the second curtain-up, one of the main characters in this body-swap farce finds out that her mid-cycle cramps are really uterine cancer, ha ha, and that her insurance won’t cover it, tee hee. The rich guy who’s learning how the other half lives runs a health insurance company, though, so don’t worry: at the very moment when this play becomes, very briefly and for the wrong reasons but nonetheless interesting, all obstacles are removed, all jeopardy lost, by the single line, “I’ll take care of it.” So much for drama.

But it is impressive how accurately the playwrights have captured one particular scene in a doctor’s office, when a blasé physician proves more skilled at the circular logic of managed care – in which the patient, based on the limitations of coverage, is denied diagnostic tests that might save her life – than at medicine. Anyone who has had this conversation with the doctor she thought was her ally (“I could recommend the procedure, but I see no reason to do so, and your insurance will deny it anyway”) will feel perhaps the evening’s only genuine emotion, a chill of recognition. This second-act subplot, or rather the intention behind it to raise an artistic voice against a great injustice of American life, alone salvages this script from utter worthlessness. Alas, what it’s doing in this farcical territory can best be termed trespassing.

But this production, apart from the writing (far, far apart), has many merits. The physical production is admirably of-a-piece. Ms. Bergh’s costumes are exactly in line with Marcia Milgrom Dodge’s no-obviousness-underplayed direction, and who can blame these women? To direct or design with subtlety for a piece like this would be like trying to paint camouflage onto an atom bomb after it’s exploded. Lighting designer Jared A. Sayeg so fully embraces Ms. Dodge’s ethos as to employ two-foot-tall red-and-blue flashing cop-car lights, merely to transition from one scene to another, one single time. John Iacovelli’s incredibly profuse and attractive sets at first seem slickly realistic, until the pile-up of locations and track-movers and scene wagons and traps makes clear that over-the-top is a concept of volume as much as it is one of design.

So is the casting; Michael Donovan once again brings a host of very good actors, from the game leads and enthusiastic support to the adorably rebellious three-scene tween (Danielle Soibelman). The swing cast consists of the well-timed Tim Bagley and Playhouse perennial (and wife to artistic director Sheldon Epps) Monette Magrath. They do what can be done with a play that makes comic fodder of senile dementia, cancer, a venal health care system, matching siren-howl Staten Island accents, lots of boob-jiggling, and that venerable knee-slapper, the gynecological examination. Occasionally, heroically, these actors squeeze laughs out of the tit caught in the wringer. It’s not enough.

Don’t blame the premise. The idea of a man and woman exchanging bodies has propelled many a modern entertainment, from the 1933 H.P. Lovecraft story “The Thing on the Doorstep” to the 2002 Rob Schneider classic, The Hot Chick. Interestingly, the 1988 Craig Lucas play Prelude to a Kiss, the 1984 Carl Reiner movie All of Me, and Under My Skin all use the body-swap conceit, and all take their names from old love songs. And all three of those songs are funnier than this play.

photos by Jim Cox

Under My Skin

Pasadena Playhouse in Pasadena

ends on October 7, 2012

for tickets, call (626) 356-7529 or visit Pasadena Playhouse

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

A very kind review. I loved the sets, props, lights and costumes. Actors are amazing people. They will do anything to work. You really nailed this one.

Thank you, but don’t tell Steven Stanley. I predict at least 4 Scenies for this one, including Best World Premiere Play for Sternin & Fraser.