NEITHER WILLIAMS OR THE GOODMAN

AT THEIR BEST

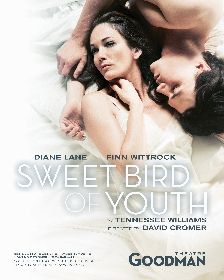

Sweet Bird of Youth is not top drawer Tennessee Williams. The play has some of Williams’ lyricism and humor, and at least one sharply etched character, but its Southern Gothic excesses are a self-parody of the playwright’s Never-Never Land Deep South. The much anticipated Goodman revival’”largely based on the red hot director David Cromer at the helm and Diane Lane as the featured star’”has its moments, but it’s an uneven presentation that doesn’t compensate for the script’s weaknesses.

The action takes place in the town of St. Cloud in a nameless state on the Gulf coast. A 29-year old gigolo named Chance Wayne has returned to his home town with Andrea Del Lago, a faded middle-aged film star who now goes by Princess Kosmonopolis. Wayne uses Del Lago to advance his failing acting career while the woman exploits Chance’s youth and sexual prowess, along with drugs and alcohol, to block out her loss of youth and fear of aging.

Years before, Wayne had been run out of town by Boss Finley, a local racist politician and demagogue, because Chance had seduced his teen-aged daughter Heavenly and infected her with a venereal disease that led to an operation leaving the girl barren. Finley has sworn to have Chance castrated if he returned to St. Cloud. After a lot of pontificating about youth and its passing, Chance, resigned to facing Finley’s thugs, elects to remain in St. Cloud after Del Lago leaves for her revived Hollywood career.

Years before, Wayne had been run out of town by Boss Finley, a local racist politician and demagogue, because Chance had seduced his teen-aged daughter Heavenly and infected her with a venereal disease that led to an operation leaving the girl barren. Finley has sworn to have Chance castrated if he returned to St. Cloud. After a lot of pontificating about youth and its passing, Chance, resigned to facing Finley’s thugs, elects to remain in St. Cloud after Del Lago leaves for her revived Hollywood career.

The play received its share of positive reviews but also absorbed criticism for its overheated story’”political corruption, venereal disease, drugs, sex, booze, and racism. Some viewers may have been shocked back then but today, that on stage behavior is less than outrageous? The play’s structure also is problematical. The show is divided into three acts, the first dominated by Chance and Del Lago. The short second act shifts to Boss Finley and the denizens of St. Cloud, and then brings Del Lago back in the final act. She is the strongest character in the play and she is much missed during her long absences from the stage, mainly because the desperate actress is a flamboyant figure, living on drugs and her nerve ends. However, Diane Lane takes a realistic approach to the lady, especially in the third act, which works against the character’s grain.

Paul Newman played Chance Wayne in the original production and invested the character with a doomed poetic quality. Finn Wittrock, with his Southern accent slipping in and out of place, is a physical hunk, but he’s a prosaic Chance, a toy boy with silly dreams about an acting career, egotistical, and a little dim. The chemistry between him and Lane is also minimal, or maybe Williams didn’t sufficiently flesh out the relationship that connects this odd couple.

Paul Newman played Chance Wayne in the original production and invested the character with a doomed poetic quality. Finn Wittrock, with his Southern accent slipping in and out of place, is a physical hunk, but he’s a prosaic Chance, a toy boy with silly dreams about an acting career, egotistical, and a little dim. The chemistry between him and Lane is also minimal, or maybe Williams didn’t sufficiently flesh out the relationship that connects this odd couple.

The usually reliable John Judd turns Boss Finley into a stereotype cartoon of Southern white supremacy. Finley should be a menacing, scary figure but at Goodman too often he’s comic relief. Kristina Johnson makes the most of her brief appearances as Heavenly, the only really tragic character in the play, but her role is woefully unwritten. The plot cries out for a strong confrontational scene between Heavenly and Chance, but it never happens.

Williams has more success with his minor characters. Jennifer Engstrom is just right as Finley’s blowsy mistress Miss Lucy. Penny Slusher contributes a welcome bit of human warmth as Aunt Nonnie, and Vincent Teninty is excellent as Finley’s bullying son Tom, Jr. Credit Goodman with employing a full 17-member ensemble, retaining several characters who are basically walk-ons. James Schuette’s set designs attempt a dreamlike atmosphere, with floor to ceiling gauzy curtains and the use of a revolving stage; both are more distracting than dramatic. However, Schuette’s costume design properly locates the narrative in the late 1950’s. Keith Parham designed the lighting, and Josh Schmidt composed the original music.

For all its weaknesses, the production moves right along, and the three-hour running time has no dead spots. But the disjointed plotting and the two-dimensional grotesques who populate the story mark this show as second tier Williams. All the lines about the passage of time and the slippage of youth may have been a very personal statement by Williams, who was undergoing severe emotional crises at the time, but they are pseudo philosophical and repetitive (the play originated as a one-act drama called The Enemy: Time.)

Before he is taken away, Chance recites the play’s final lines directly to the audience: “I don’t ask for your pity, but just for your understanding’”not even that’”no. Just for your recognition of me in you, and the enemy, time, in all of us.” I doubt that many spectators will recognize Chance in them, unless they are pill-popping gigolos deluding themselves with impossible pipe dreams and harboring a very slender sense of survival.

photos by Liz Lauren

Sweet Bird of Youth

Goodman’s Albert Theatre

scheduled to end on October 28, 2012

for tickets, call 312 443 3800 or visit Goodman

for more shows, visit Theatre in Chicago