LIKE THE LAST, AND THE ONE BEFORE THAT

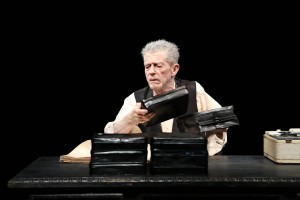

About twenty minutes into John Hurt’s solo performance Wednesday, the character Krapp’s voice on tape said, “Extraordinary silence tonight.” And as the live actor playing Krapp and the capacity house at the Kirk Douglas Theatre listened intently to this recorded mention of silence, a real live watch alarm began to chime from somewhere in the audience. Beep-beep. Beep-beep. Beep-beep. For about thirty seconds this continued unchecked, this rude barbarian rush into our civilized gathering, breaking the fragile spell in which a master illusionist had bound us by virtue of a sophisticated talent brought to bear on our politeness and forbearance. It only took one selfish brute to trash the effect of the room’s collective centuries of effort and progress. Mr. Hurt and the rest of us pretended that it hadn’t happened, but it surely did.

One of the reasons Mr. Hurt had to pretend that it hadn’t happened is that Krapp’s Last Tape is a play by Samuel Beckett, and the Beckett estate is famously eager to shut down productions that it feels stray from the playwright’s intentions. It’s remarkable how many reviews, in New York and in Los Angeles, have praised this Gate Theatre Dublin staging for “finding the humor” or “playing up the comedy.” It does nothing of the sort. Like every Beckett production sanctioned by the estate, which is to say every legitimate production, this one sticks to the letter of the written word, including the length of pauses (“Ten seconds. Fifteen seconds.”) specified in the stage directions. And the business of the banana hanging from the mouth, which I have heard mentioned (by those who should know better) as particular to this production: this too is Beckett’s, not Hurt’s, not his director Michael Colgan’s. Do the Gate artists make these theatrical gestures their own? A better question might be: Can they? Can anyone, under such constraints?

One of the reasons Mr. Hurt had to pretend that it hadn’t happened is that Krapp’s Last Tape is a play by Samuel Beckett, and the Beckett estate is famously eager to shut down productions that it feels stray from the playwright’s intentions. It’s remarkable how many reviews, in New York and in Los Angeles, have praised this Gate Theatre Dublin staging for “finding the humor” or “playing up the comedy.” It does nothing of the sort. Like every Beckett production sanctioned by the estate, which is to say every legitimate production, this one sticks to the letter of the written word, including the length of pauses (“Ten seconds. Fifteen seconds.”) specified in the stage directions. And the business of the banana hanging from the mouth, which I have heard mentioned (by those who should know better) as particular to this production: this too is Beckett’s, not Hurt’s, not his director Michael Colgan’s. Do the Gate artists make these theatrical gestures their own? A better question might be: Can they? Can anyone, under such constraints?

This 1958 play, in which an old man on his birthday listens to his own recorded philosophizing from 30 years previous and then records a new message for posterity, or for himself, is widely held to offer one of those apex roles, like Lear or Mother Courage, upon which a mature actor may bring to bear all the experience gathered over a long career. The old Krapp interacts with his younger self, laughing and cursing and searching for a capitulation with time and memory that stops short of resignation. Whether he finds it ought to be the decision of the actor and his director (I say “his” advisedly, as one of the Beckett proscriptions is gender-bent casting). But with the rules of the game so rigidly fixed against the moment’s inspiration, or the considered opinion of anyone else, it’s rare in my experience to see a Beckett play come off as a fresh collaboration much different from previous incarnations.

This 1958 play, in which an old man on his birthday listens to his own recorded philosophizing from 30 years previous and then records a new message for posterity, or for himself, is widely held to offer one of those apex roles, like Lear or Mother Courage, upon which a mature actor may bring to bear all the experience gathered over a long career. The old Krapp interacts with his younger self, laughing and cursing and searching for a capitulation with time and memory that stops short of resignation. Whether he finds it ought to be the decision of the actor and his director (I say “his” advisedly, as one of the Beckett proscriptions is gender-bent casting). But with the rules of the game so rigidly fixed against the moment’s inspiration, or the considered opinion of anyone else, it’s rare in my experience to see a Beckett play come off as a fresh collaboration much different from previous incarnations.

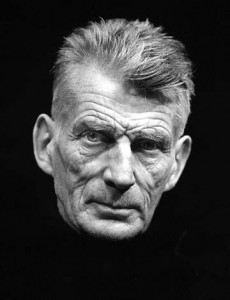

Mr. Colgan’s production takes advantage of Mr. Hurt’s physical resemblance to his author by making him up to look exactly like the most famous of Beckett’s author photographs; this is a difference, I suppose, from Mr. Colgan’s version of this play starring Michael Gambon who, though an actor capable of much diversity in his roles, will never look like the ascetic Beckett. Mr. Hurt gives a lovely, nuanced, and characteristically pat performance here. He’s been playing this part for decades, and in fact has made a film of it, but that’s not what I mean by pat. Rather, his is a style of acting, frequently seen in British actors of the Royal Academy school, that seems to invest more in the fine technical arts (how to cough believably, how to time a beat change) than in the soul-searching sense memory of the Stanislavskian schools, whose dramatic acting style is much more familiar to American audiences.

Mr. Colgan’s production takes advantage of Mr. Hurt’s physical resemblance to his author by making him up to look exactly like the most famous of Beckett’s author photographs; this is a difference, I suppose, from Mr. Colgan’s version of this play starring Michael Gambon who, though an actor capable of much diversity in his roles, will never look like the ascetic Beckett. Mr. Hurt gives a lovely, nuanced, and characteristically pat performance here. He’s been playing this part for decades, and in fact has made a film of it, but that’s not what I mean by pat. Rather, his is a style of acting, frequently seen in British actors of the Royal Academy school, that seems to invest more in the fine technical arts (how to cough believably, how to time a beat change) than in the soul-searching sense memory of the Stanislavskian schools, whose dramatic acting style is much more familiar to American audiences.

I find the RADA actors typically fascinating but mannered, their choices noticeably preselected, whereas the focus of the various Method schools is more upon the living moment, the “what new revelation can come now” theory that gives every night the potential for a new performance. The drawbacks of each are manifest: a RADA actor is trained to do the same thing in perpetuity, and if the well-planned performance never fails the show, it also may never transcend it; an actor trained by Stella Adler or Lee Strasberg, on the other hand, might have very good nights and dismal ones, since his art depends so heavily on the variabilities of psychology. So in a way, Beckett could have asked for no better Beckett performer than a RADA man (although, to be fair, I must admit a large hole in my thesis: Beckett wrote the role of Krapp for Patrick Magee, an actor vastly less controllable and predictable than any RADA ever produced).

I find the RADA actors typically fascinating but mannered, their choices noticeably preselected, whereas the focus of the various Method schools is more upon the living moment, the “what new revelation can come now” theory that gives every night the potential for a new performance. The drawbacks of each are manifest: a RADA actor is trained to do the same thing in perpetuity, and if the well-planned performance never fails the show, it also may never transcend it; an actor trained by Stella Adler or Lee Strasberg, on the other hand, might have very good nights and dismal ones, since his art depends so heavily on the variabilities of psychology. So in a way, Beckett could have asked for no better Beckett performer than a RADA man (although, to be fair, I must admit a large hole in my thesis: Beckett wrote the role of Krapp for Patrick Magee, an actor vastly less controllable and predictable than any RADA ever produced).

What would Patrick Magee have done with the moment, later in Wednesday’s show, when a second audible interruption (this time a cell phone, unanswered for at least five rings) charged the atmosphere with an opportunity for improvisation? Would he have denied the given circumstance of a ringing telephone, as Mr. Hurt did? I don’t pretend to know, and would love to hear of any such experience on the part of someone who saw Magee in live performance. But Mr. Hurt’s moment, and this entire production’s enforced slavishness to the Beckett aesthetic, strikes me as somewhat dead, in that it is not so much breathing fresh air as preserved under glass.

What would Patrick Magee have done with the moment, later in Wednesday’s show, when a second audible interruption (this time a cell phone, unanswered for at least five rings) charged the atmosphere with an opportunity for improvisation? Would he have denied the given circumstance of a ringing telephone, as Mr. Hurt did? I don’t pretend to know, and would love to hear of any such experience on the part of someone who saw Magee in live performance. But Mr. Hurt’s moment, and this entire production’s enforced slavishness to the Beckett aesthetic, strikes me as somewhat dead, in that it is not so much breathing fresh air as preserved under glass.

The very astute Colin Mitchell, in conversation this morning, defended the Beckett estate’s posture by pointing out that a Beckett play is like a poem, and that his directions are written to enhance a particular intention on the playwright’s part. This certainly is so. However, even a poem may be read in strikingly different styles. Listening to Dylan Thomas’s lugubrious pyrotechnics in his own recording of “Do not go gentle into that good night,” one may long for Anthony Hopkins’ restraint. And of course one may not. But that Mr. Hopkins had the temerity to record it can hardly be said to do the piece a disservice.

If theater is to reinvent itself for an audience so calcified that it cannot be trusted to turn off its electronic devices even after repeated admonishments, I think that reinvention will not look like this show. It will have more input from adventurous companies like Impro Theatre, who even tonight, just a mile or two from the Kirk Douglas at the Odyssey, will perform several pieces of original literature, invented on the spot, never to be seen again: a theatrical experience so pure that it makes the Gate Theatre’s Krapp’s Last Tape look like a VHS recording.

production photos by Ryan Miller

Krapp’s Last Tape

The Gate Theatre Dublin

Center Theatre Group’s Kirk Douglas Theatre in Culver City

scheduled to end on November 4, 2012

for tickets, call (213) 628-2772 or visit CTG