SHOOTING HISTORY IN THE NECK

With the exception of Hedwig and the Angry Inch and its fierce gender-bending genius, and Rocky Horror Picture Show (sublime sexy silliness that nudged a million budding transvestites into their corsets and fishnets just that much sooner), the genre of rock musicals, in general, is an overrated bore. My verité-besotted friends gushed that Rent is “our generation’s La Boheme!” – but I found it preachy and tendentious. Even Hair and its fabulous tunes contains a story which hasn’t aged well (the revival’s earnest Age of Aquarius happy-hippie millennialism felt as fake and sad as Haight-Ashbury’s Made-in-China tie-dye T-shirts). And the rock opera Tommy may have been brilliant as an album, but suffers in the theater from uncompelling storytelling.

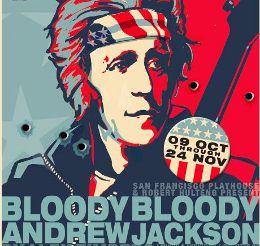

Now comes Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson, described as a rock musical version of the life and legacy of our country’s 7th president; when assigned to review the production at SF Playhouse’s spanking new digs, I had trepidations. A historical rock musical? Would it contain choppy storytelling along with a sugar-coated civics lesson a la 1776? The 2009 off-Broadway production, with book by Alex Timbers and music and lyrics by Michael Friedman, won numerous awards in New York, and was popular enough to move to Broadway. If those hard-nosed, finicky New Yorkers liked it, and since revivals are breaking out around the country (another opened this week in Chicago), maybe this is the rock musical that intertwines history, storytelling, and song in such a way as to invalidate my heebie-jeebies about the genre.

Now comes Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson, described as a rock musical version of the life and legacy of our country’s 7th president; when assigned to review the production at SF Playhouse’s spanking new digs, I had trepidations. A historical rock musical? Would it contain choppy storytelling along with a sugar-coated civics lesson a la 1776? The 2009 off-Broadway production, with book by Alex Timbers and music and lyrics by Michael Friedman, won numerous awards in New York, and was popular enough to move to Broadway. If those hard-nosed, finicky New Yorkers liked it, and since revivals are breaking out around the country (another opened this week in Chicago), maybe this is the rock musical that intertwines history, storytelling, and song in such a way as to invalidate my heebie-jeebies about the genre.

No such luck.

For all of Jackson’s irreverence and timeliness – and SF Playhouse’s production values – it was difficult to get on board with Jackson from the beginning, which started with the appearance of The Storyteller (Ann Hopkins), a schoolmarm whirling around the stage in a motorized wheelchair (hey, isn’t that Bette Midler’s mermaid shtick?). Her job was to force-feed morsels of information to the audience, getting us up to speed on the dramatic events of Andrew Jackson’s early life in the frontier wilds of 18th century Tennessee. Apparently Andrew Jackson isn’t too keen on The Storyteller, either. In a funny but mystifying twist, Jackson pulls out his pistol and shoots her, then stuffs her body down a hole in the center of the stage. Perhaps it’s his way of blowing away the orthodox historical interpretations of his life, clearing the way for the sexier punk-rock version we see unfolding before us. The Storyteller gets the last laugh, however – she returns later in the show, somehow resurrected, saying “You can’t shoot history in the neck!” (one of many memorable punch lines that help to buoy an otherwise uneven script). This and a grab-bag of other anachronistic theatrical tricks (references to “manscaping” and “teabagging” come to mind), quickly establish the show’s sassy, iconoclastic take on history. As tart and pleasing as these gimmicks might be, they are overused like little bitch-slaps, employed so that we won’t notice the hollow enterprise underneath.

For all of Jackson’s irreverence and timeliness – and SF Playhouse’s production values – it was difficult to get on board with Jackson from the beginning, which started with the appearance of The Storyteller (Ann Hopkins), a schoolmarm whirling around the stage in a motorized wheelchair (hey, isn’t that Bette Midler’s mermaid shtick?). Her job was to force-feed morsels of information to the audience, getting us up to speed on the dramatic events of Andrew Jackson’s early life in the frontier wilds of 18th century Tennessee. Apparently Andrew Jackson isn’t too keen on The Storyteller, either. In a funny but mystifying twist, Jackson pulls out his pistol and shoots her, then stuffs her body down a hole in the center of the stage. Perhaps it’s his way of blowing away the orthodox historical interpretations of his life, clearing the way for the sexier punk-rock version we see unfolding before us. The Storyteller gets the last laugh, however – she returns later in the show, somehow resurrected, saying “You can’t shoot history in the neck!” (one of many memorable punch lines that help to buoy an otherwise uneven script). This and a grab-bag of other anachronistic theatrical tricks (references to “manscaping” and “teabagging” come to mind), quickly establish the show’s sassy, iconoclastic take on history. As tart and pleasing as these gimmicks might be, they are overused like little bitch-slaps, employed so that we won’t notice the hollow enterprise underneath.

In a series of frantically-paced scenes punctuated by mostly forgettable songs, we take in the salient facts of Jackson’s life and political legacy: His family is slaughtered by Indians when he’s a young boy, planting the seed of a life-long hatred for America’s first peoples, whom he considered “despicable creatures, savages, soulless, godless” – a convenient slice of childhood-trauma motivation to keep that plot machinery humming merrily along); his marriage to Rachel, a relationship troubled by scandalous rumors of bigamy and a perverse undercurrent of sado-masochism (Andrew Jackson was apparently a self-cutter); his rise as America’s first superstar president, a megalomaniac Populist who founded the Democratic Party and proclaimed himself champion of the will of The People, not those despicable and corrupt Washington elites (many spectators will be dutifully thinking how apropos this is to our current political situation – plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose); and his ruthless removal (or outright slaughter) of Indian tribes from the eastern U.S., culminating in the infamous resettlement program that became known as the Trail of Tears. This last theme was the only one that really hit home, mostly due to the emotional punch delivered by the song “10 Little Indians” (sung by El Beh) which combines the driving rhythm of a children’s ditty with gallows-humor rhymes, forcing a relentless countdown to genocide; it induced the same shivers as some of Kurt Weill’s best and bleakest lyrics.

In a series of frantically-paced scenes punctuated by mostly forgettable songs, we take in the salient facts of Jackson’s life and political legacy: His family is slaughtered by Indians when he’s a young boy, planting the seed of a life-long hatred for America’s first peoples, whom he considered “despicable creatures, savages, soulless, godless” – a convenient slice of childhood-trauma motivation to keep that plot machinery humming merrily along); his marriage to Rachel, a relationship troubled by scandalous rumors of bigamy and a perverse undercurrent of sado-masochism (Andrew Jackson was apparently a self-cutter); his rise as America’s first superstar president, a megalomaniac Populist who founded the Democratic Party and proclaimed himself champion of the will of The People, not those despicable and corrupt Washington elites (many spectators will be dutifully thinking how apropos this is to our current political situation – plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose); and his ruthless removal (or outright slaughter) of Indian tribes from the eastern U.S., culminating in the infamous resettlement program that became known as the Trail of Tears. This last theme was the only one that really hit home, mostly due to the emotional punch delivered by the song “10 Little Indians” (sung by El Beh) which combines the driving rhythm of a children’s ditty with gallows-humor rhymes, forcing a relentless countdown to genocide; it induced the same shivers as some of Kurt Weill’s best and bleakest lyrics.

For 90 minutes, the young and energetic cast, under Jon Tracy’s stage-filling direction, works very hard to slam dance their way through the show, but even their considerable pluck doesn’t elevate the production beyond the reach of its all-too-frequent stretches of drag. They bounce around the set with plenty of garage-band bravado, doing their best to overcome spotty amplification, yet the vocals never rise to the intensely raucous, bad-ass level you’d expect from rock-inspired performances. Playing Andrew Jackson, Ashkon Davaran serves up his songs with a mix of humor and savagery that conveys some of the ruthlessness and borderline madness of his character. As Jackson’s sensitive and suffering wife, Angel Burgess brings us into the painful and lonely world of a larger-than-life politician’s spouse – it’s not easy being First Lady to a personality cult; her lament about the growing estrangement from her politically ambitious husband (“The Great Compromise”) takes the time to pull us in and let us feel her desolation. As Martin Van Buren, Michael Barrett Austin – Jackson’s Vice President and loyal henchman in his pitched battles with political rivals – shows astute comedic instincts and puts a delightfully dark and rather fey spin on the man who would take over the White House after Jackson. Another standout is Safiya Fredericks, who plays both Henry Clay (one of Jackson’s many bitter political enemies) and Black Fox, an Indian leader who initially allies himself with Jackson to overpower rival tribes. Black Fox’s journey is perhaps one of the saddest in the show, as we see him realize, too late, the terrible mistake he’s made in tying his fate to a man bent on finding a Final Solution to the Indian problem.

For 90 minutes, the young and energetic cast, under Jon Tracy’s stage-filling direction, works very hard to slam dance their way through the show, but even their considerable pluck doesn’t elevate the production beyond the reach of its all-too-frequent stretches of drag. They bounce around the set with plenty of garage-band bravado, doing their best to overcome spotty amplification, yet the vocals never rise to the intensely raucous, bad-ass level you’d expect from rock-inspired performances. Playing Andrew Jackson, Ashkon Davaran serves up his songs with a mix of humor and savagery that conveys some of the ruthlessness and borderline madness of his character. As Jackson’s sensitive and suffering wife, Angel Burgess brings us into the painful and lonely world of a larger-than-life politician’s spouse – it’s not easy being First Lady to a personality cult; her lament about the growing estrangement from her politically ambitious husband (“The Great Compromise”) takes the time to pull us in and let us feel her desolation. As Martin Van Buren, Michael Barrett Austin – Jackson’s Vice President and loyal henchman in his pitched battles with political rivals – shows astute comedic instincts and puts a delightfully dark and rather fey spin on the man who would take over the White House after Jackson. Another standout is Safiya Fredericks, who plays both Henry Clay (one of Jackson’s many bitter political enemies) and Black Fox, an Indian leader who initially allies himself with Jackson to overpower rival tribes. Black Fox’s journey is perhaps one of the saddest in the show, as we see him realize, too late, the terrible mistake he’s made in tying his fate to a man bent on finding a Final Solution to the Indian problem.

Visually the production has a raw and punchy verve that serves the rocker esthetic of the show. Nina Ball’s set design includes a large hemisphere of exposed girders looming over the stage, suggesting the metal skeleton of the U.S. Capitol’s dome – like the young country, still a “work in progress.” No-frills scaffolding creates platforms scattered throughout the framework, used most effectively during the larger ensemble numbers when the audience can see the performers thrashing about with their instruments at various levels. The center stage’s floor (dramatically expanded when SF Playhouse recently took over this space, now built out to bury the first several rows of orchestra seats) is emblazoned with a gigantic American eagle, which in the context of this show looks appropriately more like a tattoo than the symbol of the U.S. The costumes (Abra Berman, Tatjana Genser) were more grunge than glam, not elaborate but festooned with enough period details to provide some cues about the historical era. The lighting design (Kurt Landisman) is tailor-made for a rock concert: saturated colors, hot spotlights, fast cutaways, and dramatic blackouts (the only things missing were fireworks and smoke bombs). All those extra lighting instruments come at a cost, however. From where we were sitting in the balcony, sight-line interference and heat were problematic.

Visually the production has a raw and punchy verve that serves the rocker esthetic of the show. Nina Ball’s set design includes a large hemisphere of exposed girders looming over the stage, suggesting the metal skeleton of the U.S. Capitol’s dome – like the young country, still a “work in progress.” No-frills scaffolding creates platforms scattered throughout the framework, used most effectively during the larger ensemble numbers when the audience can see the performers thrashing about with their instruments at various levels. The center stage’s floor (dramatically expanded when SF Playhouse recently took over this space, now built out to bury the first several rows of orchestra seats) is emblazoned with a gigantic American eagle, which in the context of this show looks appropriately more like a tattoo than the symbol of the U.S. The costumes (Abra Berman, Tatjana Genser) were more grunge than glam, not elaborate but festooned with enough period details to provide some cues about the historical era. The lighting design (Kurt Landisman) is tailor-made for a rock concert: saturated colors, hot spotlights, fast cutaways, and dramatic blackouts (the only things missing were fireworks and smoke bombs). All those extra lighting instruments come at a cost, however. From where we were sitting in the balcony, sight-line interference and heat were problematic.

Is this show more fun and intriguing than a history lecture? Oh, hell yes. Does it reveal some down-and-dirty truths about Andrew Jackson (“The man who put The Man in Manifest Destiny!”) and the sordid violence of our country’s past? Perhaps. Does it hold a convincing – if cracked — mirror up to our current political circus? Judging from the chatter overheard after the show (“Wasn’t Jackson, like, a total Tea-partyer?”), some might argue so. Will it join the ranks of the very few rock musicals that have become classics? Sorry, that’s one you’ll bloody well have to answer yourself.

photos by Jessica Palopoli

Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson

San Francisco Playhouse (new address: 450 Post St.)

scheduled to end on Nov 24, 2012

for tickets, call 415-677-9596 or http://www.sfplayhouse.org

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

Can’t wait!