A POWERFUL WASTELAND AT TIMELINE

Wasteland is a two-character play but the audience only sees one in this drama about two American soldiers held as prisoners during the Vietnam War, now receiving a gripping world premiere at TimeLine. The other character is separated behind a wall in a connecting room. The rooms exist an in underground cave in an unknown location; it could be in Vietnam, or some other country embroiled in the Vietnam War. But for the POWs, their world is shrunk to their cramped cells and outside life may as well not exist. While the production is brilliantly performed and thought provoking, it’s grueling for the performers and grueling for the audience.

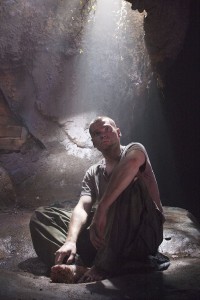

Joe, who has been living in isolation as a POW for six months, is joined by Riley, known only by his voice on the other side of the wall. During the 100 minute show, which covers 18 months of captivity, the two kill time bantering and arguing, anything to break up the boredom and loneliness, fear, homesickness, and desperation that swamp their lives in their claustrophobic subterranean world.

Joe, who has been living in isolation as a POW for six months, is joined by Riley, known only by his voice on the other side of the wall. During the 100 minute show, which covers 18 months of captivity, the two kill time bantering and arguing, anything to break up the boredom and loneliness, fear, homesickness, and desperation that swamp their lives in their claustrophobic subterranean world.

The audience learns that Joe is gay. He’s from the Northeast leading to immediate culture clashes with Riley, a good old boy Texan. Joe is bitter toward the government for what he perceives as their botching of the war and their indifference toward the troops in the field. Riley is a super patriot. For him, the government can do no wrong and any sacrifice is justified to hold back the tide of Communism from American shores. President Nixon will find a way to get them out of Vietnam and back to the United States.

To pass the time and to keep up their spirits, the two men play word games, argue over the movies, and sing songs. Predictably, they also get on each other’s nerves. The two are separated by their political views and by Joe’s homosexuality (Riley is unapologetically homophobic). But in the end they cling to each other emotionally and psychologically in spite of the separating wall. They urgently need each other to get through their ordeal, which could last indefinitely if death doesn’t intervene.

The playwright is local writer, actor, director Susan Felder. Her script doggedly relies on obscenities, the natural lingo of the two prisoners, but there is some black humor in the dialogue and a couple of the verbal confrontations which crackle with tension, especially the furious debate over the justification of the war. The bottom line is that Felder’s writing takes flight in live performance, or at least in the electric TimeLine performances.

The playwright is local writer, actor, director Susan Felder. Her script doggedly relies on obscenities, the natural lingo of the two prisoners, but there is some black humor in the dialogue and a couple of the verbal confrontations which crackle with tension, especially the furious debate over the justification of the war. The bottom line is that Felder’s writing takes flight in live performance, or at least in the electric TimeLine performances.

Felder’s writing portrays the resilience of the human spirit under intolerable conditions produced by the brutality of war. Even knowing that this specific play may be fiction, it’s hard to watch, as its story was acted out hundreds of times during the Vietnam War, with American POW’s penned up under vile conditions in prisons scattered throughout the war zone. Wasteland is a language rather than a physical drama, expressive and occasionally eloquent for all its reliance on profanity.

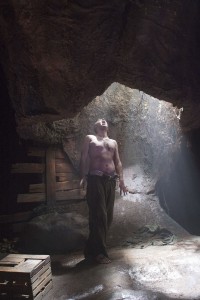

The play makes daunting demands on the two actors and director William Brown keeps the story taut and fluid, extracting performances of remarkable commitment from his two-actor ensemble. Nate Burger gives a wondrous performance as Joe, the on stage prisoner. He rings all the emotional changes on the character’s imprisonment—bitterness, anger, a determination to keep his sanity at all costs, and occasional glimmers of hope that dissolve into despair. Steve Haggard has an equally taxing role as Riley, with its own challenges because Haggard has to act entirely with his voice; he evokes a vivid picture of a young man outwardly full of bravado but inwardly ready to crack under the strain of his imprisonment. Burger and Haggard make up an indelible team.

The TimeLine stage is converted into Joe’s craggy underground cell, realistically conveyed by scenic designer Kevin Depinet (Rachel Anne Healy’s costumes, Jesse Klug’s lighting, and Andrew Hansen’s sound solidify the oppressive atmosphere). The cramped set confines Joe to a few square yards of space where he does calisthenics and tries to keep his living space reasonably tidy.

Wasteland necessarily skims over some externals. We never see how the prisoners get their food, or how Joe keeps his barren cell free of human waste. He doesn’t shave and his hair doesn’t grow. His jailers never appear, and are only briefly heard in off-stage chatter. So even though a year and a half pass, time seems to stand still, as it does for the prisoners who battle tedium and discomfort and depression in the days without end that face them.

photos by Lara Goetsch

Wasteland

TimeLine Theatre

ends on December 30, 2012

for tickets, call 773 281 8463 or visit TimeLine

for more shows, visit Theatre in Chicago